Catacombe dei Cappuccini

The Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo (also Catacombe dei Cappuccini or Catacombs of the Capuchins) are burial catacombs in Palermo, Sicily, southern Italy. Today they provide a somewhat macabre tourist attraction as well as an extraordinary historical record.

Historical background

Palermo's Capuchin monastery outgrew its original cemetery in the 16th century and monks began to excavate crypts below it. In 1599 they mummified one of their number, recently dead brother Silvestro of Gubbio, and placed him into the catacombs.

The bodies were dehydrated on the racks of ceramic pipes in the catacombs and sometimes later washed with vinegar. Some of the bodies were embalmed and others enclosed in sealed glass cabinets. Friars were preserved with their everyday clothing and sometimes with ropes they had worn as a penance.

Originally the catacombs were intended only for the dead friars. However, in the following centuries it became a status symbol to be entombed into the Capuchin catacombs. In their wills, local luminaries would ask to be preserved in certain clothes, or even to have their clothes changed at regular intervals. Priests wore their clerical vestments, others were clothed according to the contemporary fashion. Relatives would visit to pray for the deceased and also to maintain the body in presentable condition.

The catacombs were maintained through the donations of the relatives of the deceased. Each new body was placed in a temporary niche and later placed into a more permanent place. As long as the contributions continued, the body remained in its proper place but when the relatives did not send money any more, the body was put aside on a shelf until they resumed payments.

Interments

The last friar interred into the catacombs was Brother Riccardo in 1871 but other famous people were still interred. The catacombs were officially closed in 1880 but tourists continued to visit. The last burials are from the 1920s. One of the last to be interred was Rosalia Lombardo, then nearly two years old, whose body is still remarkably intact, preserved with a procedure. The embalming procedure, performed by Professor Alfredo Salafia, consisted of formalin to kill bacteria, alcohol to dry the body, glycerin to keep her from overdrying, salicylic acid to kill fungi, and the most important ingredient, zinc salts (zinc sulfate and zinc chloride) to give the body rigidity.[1][2] The formula is 1 part glycerin, 1 part formalin saturated with both zinc sulfate and chloride, and 1 part of an alcohol solution saturated with salicylic acid.

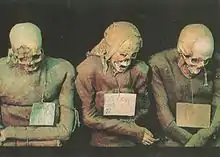

The catacombs contain about 8000 corpses and 1252 mummies (as stated by last census made by EURAC in 2011) that line the walls. The halls are divided into categories: Men, Women, Virgins, Children, Priests, Monks, and Professionals. Some bodies are better preserved than others. Some are set in poses; for example, two children are sitting together in a rocking chair. The coffins were accessible to the families of the deceased so that on certain days the family could hold their hands and they could "join" their family in prayer.

Famous people buried in the catacombs include:

- Colonel Enea DiGuiliano (in French Bourbon uniform)

- Salvatore Manzella, surgeon

- Lorenzo Marabitti, sculptor

- Giovanni Paterniti, an American Vice-Consul who died in Palermo in 1911

- Filipo Pennino, sculptor

- Son of a king of Tunis who had converted to Catholicism

- Giuseppe Velasco also called Velásquez the Sicilian painter of Chinese Palace in Palermo.

- Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa is sometimes said to be buried in the catacombs, but he is buried in the cemetery next to them.

Scientific research

The Sicily Mummy Project was created in 2007, to study the mummies and to create profiles on those that were mummified. The project is led by the anthropologist Dario Piombino-Mascali of the Department of Cultural Heritage and Sicilian Identity in Palermo, and is backed by the European Academy of Bozen/Bolzano[3][4] The mummies are X-Rayed and given CT scans in order to preserve the mummies, along with other anthropolicial and paleopathological techniques to confirm the age, and sex of the individuals. Piombino-Mascali credits the program with re-opening the discussion about death in Sicily;

For many years the subject of death was taboo [in Sicily]. Now, given the scientific importance of what's emerging with these mummies, people are understanding that in Sicily, death has always been part of life. And for centuries many Sicilians were using mummification to make sure there was a constant relationship between life and death.

— Dario Piombino-Mascali, January 2013, Archaeology News Network

Forensic biologist Mark Benecke identified several insects that shed a light on the process of mummification.[5]

Tourism

The catacombs are open to the public and taking photographs inside is supposedly prohibited, with prominent signs making it clear to visitors that photography is not allowed. However, the bodies have been shown on film in Francesco Rosi's Cadaveri Eccellenti ("Illustrious Corpses"), and television programmes such as the Channel 4 series Coach Trip, BBC TV series The Human Body in 1998, Francesco's Italy: Top to Toe, Ghosthunting With Paul O'Grady and Friends on ITV2 in 2008 and The Learning Channel in 2000. Iron grills have been installed to prevent tourists tampering or posing with the corpses.[6]

Gallery

New Corridor

New Corridor Monks' Corridor

Monks' Corridor Women's Corridor

Women's Corridor

See also

- Capuchin Crypt, in Rome Italy

- Capela dos Ossos, in Évora, Portugal

References

- Lange, Karen (January 26, 2009). "Lost "Sleeping Beauty" Mummy Formula Found". National Geographic News.

- Piombino-Mascali, Dario; Aufderheide, Arthur C.; Johnson-Williams, Melissa; Zink, Albert R. (March 2009). "The Salafia method rediscovered". Virchows Archiv. 454 (3): 355–357. doi:10.1007/s00428-009-0738-6. PMID 19205728.

- King, Carol (2013-04-12). "Sicilian Mummy Project Reveals How People Lived Centuries Ago". ITALY Magazine. Retrieved 2018-10-31.

- Berlin, Jeremy (2013-01-29). "Sicilian Mummies Bring Centuries to Life". The National Geographic. Retrieved 2018-10-31.

- Baumjohann, Kristina; Benecke, Mark. "Insect Traces and the Mummies of Palermo — a Status Report". Entomologie heute. 31: 73–93. Retrieved April 6, 2020. [.pdf]

- Piombino-Mascali, Dario; Aufderheide, Arthur C.; Panzer, Stephanie; Zink, Albert R. (June 2010). "Mummies from Palermo". In Wieczorek, Alfred; Rosendahl, Wilfried (eds.). Mummies of the World. The Dream of Eternal Life. New York: Prestel. pp. 357–361. ISBN 978-3791350301.