Canadian raising

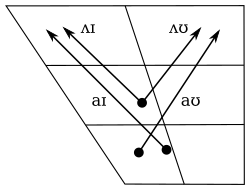

Canadian raising is an allophonic rule of phonology in many dialects of North American English that changes the pronunciation of diphthongs with open-vowel starting points. Most commonly, the shift affects /aɪ/ (![]() listen) or /aʊ/ (

listen) or /aʊ/ (![]() listen), or both, when they are pronounced before voiceless consonants (therefore, in words like price and clout, respectively, but not in prize and cloud). In North American English, /aɪ/ and /aʊ/ usually begin in an open vowel [ä~a], but through raising they shift to [ɐ] (

listen), or both, when they are pronounced before voiceless consonants (therefore, in words like price and clout, respectively, but not in prize and cloud). In North American English, /aɪ/ and /aʊ/ usually begin in an open vowel [ä~a], but through raising they shift to [ɐ] (![]() listen), [ʌ] (

listen), [ʌ] (![]() listen) or [ə] (

listen) or [ə] (![]() listen). Canadian English often has raising in words with both /aɪ/ (height, life, psych, type, etc.) and /aʊ/ (clout, house, south, scout, etc.), while a number of U.S. English dialects (such as Inland North and Western New England) have this feature in /aɪ/ but not /aʊ/.

listen). Canadian English often has raising in words with both /aɪ/ (height, life, psych, type, etc.) and /aʊ/ (clout, house, south, scout, etc.), while a number of U.S. English dialects (such as Inland North and Western New England) have this feature in /aɪ/ but not /aʊ/.

In the U.S., aboot [əˈbut], an exaggerated version of the raised pronunciation of about [əˈbʌʊt], is a stereotype of Canadian English.[1]

Although the symbol ⟨ʌ⟩ is defined as an open-mid back unrounded vowel in the International Phonetic Alphabet, ⟨ʌɪ⟩ or ⟨ʌʊ⟩ may signify any raised vowel that contrasts with unraised /aɪ/ or /aʊ/, when the exact quality of the raised vowel is not important in the given context.

Description

Phonetic environment

In general, Canadian raising affects vowels before voiceless consonants like /f/, /θ/, /t/, and /s/. Vowels before voiced consonants like /v/, /ð/, /d/, and /z/ are usually not raised.

However, several studies indicate that this rule is not completely accurate, and have attempted to formulate different rules.

A study of three speakers in Meaford, Ontario, showed that pronunciation of the diphthong /aɪ/ fell on a continuum between raised and unraised. Raising is influenced by voicing of the following consonant, but it may also be influenced by the sound before the diphthong. Frequently the diphthong was raised when preceded by a coronal: in gigantic, dinosaur, and Siberia.[2]

Raising before /r/, as in wire, iris, and fire, has been documented in some American accents.[3]

Raising of /aɪ/ before certain voiced consonants is most prominent in the Inland North, Western New England, and Philadelphia.[4] It has been noted to occur before [d], [ɡ] and [n] especially. Hence, words like tiny, spider, cider, tiger, dinosaur, cyber-, beside, idle (but sometimes not idol), and fire may contain a raised nucleus. (Also note that in six of those nine words, /aɪ/ is preceded by a coronal consonant; see above paragraph. In five [or possibly six] of those nine words, the syllable after the syllable with /aɪ/ contains a liquid.) The use of [ʌɪ] rather than [aɪ] in such words is unpredictable from phonetic environment alone, though it may have to do with their acoustic similarity to other words that do contain [ʌɪ] before a voiceless consonant, per the traditional Canadian-raising system. Hence, some researchers have argued that there has been a phonemic split in these dialects; the distribution of the two sounds is becoming more unpredictable among younger speakers.[4]

Raising can apply to compound words. Hence, the first vowel in high school [ˈhʌɪskul] as a term meaning "a secondary school for students approximately 14–18 years old" may be raised, whereas high school [ˌhaɪ ˈskul] with the literal meaning of "a school that is high (e.g. in elevation)" is unaffected. (The two terms are also distinguished by the position of the stress accent, as shown.) The same is true of "high chair".[5]

However, frequently it does not. One study of speakers in Rochester, New York and Minnesota found a very inconsistent pattern of /aɪ/ raising before voiceless consonants in certain prefixes; for example, the numerical prefix bi- was raised in bicycle but not bisexual or bifocals. Likewise, the vowel was consistently kept low when used in a prefix in words like dichotomy and anti-Semitic. This pattern may have to do with stress or familiarity of the word to the speaker; however, these relations are still inconsistent.[6]

In most dialects of North American English, intervocalic /t/ and /d/ are pronounced as an alveolar flap [ɾ] when the following vowel is unstressed or word-initial, a phenomenon known as flapping. In accents with both flapping and Canadian raising, /aɪ/ or /aʊ/ before a flapped /t/ may still be raised, even though the flap is a voiced consonant. Hence, while in accents without raising, writer and rider are pronounced identically except for a slight difference in vowel length due to pre-fortis clipping, in accents with raising, the words may be distinguished by their vowels: writer [ˈɹʌɪɾɚ], rider [ˈɹaɪɾɚ].[7]

Result

The raised variant of /aɪ/ typically becomes [ɐɪ], while the raised variant of /aʊ/ varies by dialect, with [ɐʊ~ʌʊ] more common in Western Canada and a fronted variant [ɜʊ~ɛʊ] commonly heard in Central Canada.[1] In any case, the open vowel component of the diphthongs changes to a mid vowel ([ʌ], [ɐ], [ɛ] or [ə]).

Geographic distribution

Inside Canada

As its name implies, Canadian raising is found throughout most of Canada, though the exact phonetic quality of Canadian raising may differ throughout the country. In raised /aɪ/, the first element tends to be farther back in Quebec and the Canadian Prairies and Maritimes (particularly in Alberta): thus, [ʌʊ]. The first element tends to be the farthest forward in eastern and southern Ontario: thus, [ɛʊ~ɜʊ].[8] Newfoundland English is the Canadian dialect that participates least in any conditioned Canadian raising, while Vancouver English may lack the raising of /aɪ/ in particular.[9]

Outside Canada

Canadian raising is not restricted to Canada. Raising of both /aɪ/ and /aʊ/ is common in eastern New England, for example in some Boston accents (the former more likely than the latter),[10] as well as in the Upper Midwest. South Atlantic English and the accents of England's Fens feature it as well.

Raising of just /aɪ/ is found in a much greater number of dialects in the United States. This phenomenon is most consistently found in the Inland North, the Upper Midwest, New England, New York City, and the mid-Atlantic areas of Pennsylvania (including Philadelphia), Maryland, and Delaware, as well as in Virginia.[10][11][9] It is somewhat less common in the lower Midwest, the West, and the South. However, there is considerable variation in the raising of /aɪ/, and it can be found inconsistently throughout the United States.[9]

The raising of /aɪ/ is also present in Ulster English, spoken in the northern region of the island of Ireland, in which /aɪ/ is split between the sound [ä(ː)e] (before voiced consonants or in final position) and the sound [ɛɪ~ɜɪ] (before voiceless consonants but also sometimes in any position); phonologist Raymond Hickey has described this Ulster raising as "embryonically the situation" for Canadian raising.[12]

Notes

- Boberg 2004, p. 360.

- Hall 2005, pp. 194–5.

- Vance 1987, p. 200.

- Fruehwald 2007.

- Vance 1987, pp. 197–8.

- Vance 1987.

- Vance 1987, p. 202.

- Boberg, Charles (2008). "Regional Phonetic Differentiation in Standard Canadian English". Journal of English Linguistics, 36(2), 129–154, p. 140-141. https://doi.org/10.1177/0075424208316648

- Labov et al. 2005, p. 203.

- Boberg 2010, p. 156.

- Kaye 2012.

- Hickey 2007, p. 335.

Bibliography

- Boberg, Charles (2004). "English in Canada: phonology". In Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.). A Handbook of Varieties of English. Volume 1: Phonology. Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 351–365. ISBN 978-3-11-017532-5.

- Boberg, Charles (2010). The English Language in Canada: Status, History and Comparative Analysis. Studies in English Language. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87432-8.

- Britain, David (1997). "Dialect Contact and Phonological Reallocation: 'Canadian Raising' in the English Fens". Language in Society. 26 (1): 15–46. doi:10.1017/S0047404500019394. ISSN 0047-4045.

- Chambers, J. K. (1973). "Canadian Raising". Canadian Journal of Linguistics. 18 (2): 113–135. doi:10.1017/S0008413100007350. ISSN 0008-4131.

- Dailey-O'Cain, Jennifer (1997). "Canadian Raising in a Midwestern U.S. City". Language Variation and Change. 9 (1): 107–120. doi:10.1017/s0954394500001812. ISSN 1469-8021.

- Fruehwald, Josef T. (2007). "The Spread of Raising: Opacity, lexicalization, and diffusion" (PDF). College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal. University of Pennsylvania.

- Hall, Kathleen Currie (2005). Alderete, John; Han, Chung-hye; Kochetov, Alexei (eds.). Defining Phonological Rules over Lexical Neighbourhoods: Evidence from Canadian Raising (PDF). West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics. Somerville, Massachusetts: Cascadilla Proceedings Project. ISBN 978-1-57473-407-2.

- Hickey, Raymond (2007). Irish English: History and Present-day Forms. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85299-9.

- Kaye, Jonathan (2012). "Canadian Raising, Eh?". In Cyran, Eugeniusz; Kardela, Henryk; Szymanek, Bogdan (eds.). Sound Structure and Sense: Studies in Memory of Edmund Gussmann. Lublin, Poland: Wydawnictwo KUL. pp. 321–352. ISBN 978-83-7702-381-5.

- Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (2005). The Atlas of North American English: Phonetics, Phonology and Sound Change. Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-020683-8.

- Labov, William (1963). "The Social Motivation of a Sound Change". Word. 19 (3): 273–309. doi:10.1080/00437956.1963.11659799. ISSN 0043-7956.

- Rogers, Henry (2000). The Sounds of Language: An Introduction to Phonetics. Essex: Pearson Education Limited. ISBN 978-0-582-38182-7.

- Vance, Timothy J. (1987). "'Canadian Raising' in Some Dialects of the Northern United States". American Speech. 62 (3): 195–210. doi:10.2307/454805. ISSN 1527-2133. JSTOR 454805. S2CID 1081730.

- Wells, John C. (1982). Accents of English. Cambridge University Press.