Camelina sativa

Camelina sativa is a flowering plant in the family Brassicaceae and is usually known in English as camelina, gold-of-pleasure, or false flax, also occasionally wild flax, linseed dodder, German sesame, and Siberian oilseed. It is native to Europe and to Central Asian areas. This plant is cultivated as oilseed crop mainly in Europe and in North America.

| Camelina sativa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Brassicales |

| Family: | Brassicaceae |

| Genus: | Camelina |

| Species: | C. sativa |

| Binomial name | |

| Camelina sativa | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Description

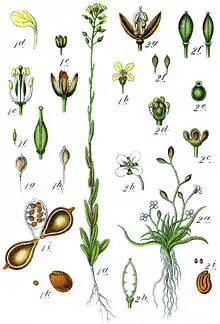

As a summer or winter annual plant, camelina grows to heights of 30–120 cm (12–47 in), with branching stems which become woody at maturity. The leaves are alternate on the stem, lanceolate with a length from 2–8 cm (0.79–3.15 in) and a width of 2–10 mm (0.079–0.394 in). Leaves and stems may be partially hairy. It blooms in the UK, between June and July.[2] Its abundant, four-petaled flowers are pale yellow in colour, and cross-shaped.[2] Later, it produces a fruit which is pear shaped with a short beak.[2] The seeds are brown,[2] or orange in colour and a length of 2–3 mm (0.079–0.118 in).[3] The 1,000-seed weight ranges from 0.8–2.0 g (0.028–0.071 oz).[4]

Distribution

Today, camelina is found, wild or cultivated, in almost all regions of Europe, Asia, and North America, but also in South America, Australia, and New Zealand.[3] Camelina seems to be particularly adapted to cold semiarid climate zone (steppes and prairies).[5]

History

C. sativa has been traditionally cultivated as an oilseed crop to produce vegetable oil and animal feed. Ample archeological evidence shows it has been grown in Europe for at least 3,000 years. The earliest findsites include the Neolithic levels at Auvernier, Switzerland (dated to the second millennium BC), the Chalcolithic level at Pefkakia in Greece (dated to the third millennium BC), and Sucidava-Celei, Romania (circa 2200 BC).[6] During the Bronze Age and Iron Age, it was an important agricultural crop in northern Greece beyond the current range of the olive.[7][8] It was also found in Denmark, and during the Stone Age in Hungary.[2] It apparently continued to be grown at the time of the Roman Empire, although its Greek and Latin names are not known.[9] As early as 600 BC, it was being sown as a monoculture around the Rhine River Valley, and was thought to have spread mainly by coexisting as a weed with flax monocultures.

Until the 1940s, camelina was an important oil crop in eastern and central Europe, and currently has continued to be cultivated in a few parts of Europe for its seed oil. Camelina oil was used in oil lamps (until the modern harnessing of natural gas, propane, and electricity) and as an edible oil (Camelina oil, also referred to as wild flax or false flax oil).[4] It was possibly brought to North America unintentionally as a weed with flaxseed, and has had limited commercial importance until modern times. Currently, the breeding potential is unexplored compared to other oilseeds commercially grown around the world.[10]

Uses

It has many uses; including the stem fibres used for brushes, the seed oil for cosmetics or burnt in lamps. Herbalists also used the oil in herbal medicine.[2]

Human food

The edible seeds[2] can be sprinkled on salads or mixed with water to produce an egg substitute.

The crop is now being researched due to its exceptionally high level (up to 45%) of omega-3 fatty acids, which is uncommon in vegetable sources. Seeds contain 38 to 43% oil and 27 to 32% protein.[11] Over 50% of the fatty acids in cold-pressed camelina oil are polyunsaturated. The oil is also very rich in natural antioxidants, such as tocopherols, making this highly stable oil very resistant to oxidation and rancidity.[12] It has 1–3% erucic acid; recently, several low-erucic and zero-erucic Camelina Sativa varieties (with erucic acid content of less than 1%) have been introduced.[12] The vitamin E content of camelina oil is approximately 110 mg/100 g. It is well suited for use as a cooking oil as it has an almond-like flavor and aroma.[13]

| 16:0 | 18:0 | 18:1 | 18:2 (omega-6) | 18:3 (omega-3) | 20:0 | 20:1 | 22:1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camelina | 7.8 | 3.0 | 16.8 | 23.0 | 31.2 | 0 | 12.0 | 2.8 |

| Canola | 6.2 | 0 | 61.3 | 21.6 | 6.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Flax | 5.3 | 3.1 | 16.2 | 14.7 | 59.6 | 0 | 0 | 0.9 |

| Sunflower | 6.0 | 4.0 | 16.5 | 72.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Biodiesel and jet fuel

The US state of Montana has recently been growing more camelina for its potential as a biofuel and biolubricant.[14] Plant scientists at the University of Idaho, Washington State University, and other institutions also are studying this emerging biodiesel.

Studies have shown camelina-based jet fuel reduces net carbon emissions by about 80%. The United States Navy chose it as the feedstock for their first test of aviation biofuel,[15] and successfully operated a static F414 engine (used in the F/A-18 Hornet and F/A-18E/F Super Hornet) in October 2009 at Naval Air Station Patuxent River, Maryland.[16] The United States Air Force also began testing the fuel in its aircraft in March 2010.[17] On 22 April 2010, the U.S. Navy observed Earth Day by conducting a flight test lasting about 45 minutes at Naval Air Station Patuxent River of an F/A-18 Super Hornet – nicknamed the "Green Hornet" – powered by a 50/50 blend of conventional jet fuel and a biofuel made from camelina; the flight was the first of a planned 15 test flights totaling about 23 flight-hours, scheduled for completion by mid-June 2010.[18] In March 2011, the U.S. Air Force successfully tested a 50/50 mix of jet propellant 8 (JP-8) and camelina-derived biofuel in an F-22 Raptor, achieving a speed of Mach 1.5 on 18 March 2011.[19] On September 4, 2011, the U.S. Navy's Blue Angels flight demonstration squadron used a 50/50 blend of camelina biofuel and jet fuel at the Naval Air Station Patuxent River Air Expo, the first time an entire military aviation unit flew on a biofuel mix.[20] In 2011, the U.S. Navy announced plans to deploy a "Great Green Fleet," a carrier battle group powered entirely by nonfossil fuels, by 2016.[21] By 2016, the U.S. Air Force wants 50% of the fuel it consumes to be from biofuels.[22]

Continental Airlines, was the first commercial airline to test a 50:50 blend of bio-derived “green jet” fuel and traditional jet fuel in the first demonstration of the use of sustainable biofuel to power a commercial aircraft in North America.( January 2009). The demonstration flight, conducted in partnership with Boeing, GE Aviation/CFM International, and Honeywell’s UOP, marked the first sustainable biofuel demonstration flight by a commercial carrier using a two-engine aircraft: a Boeing 737-800 equipped with CFM International CFM56-7B engines. Continental ran the blend in Engine No. 2. During the two-hour test flight, Continental pilots engaged the aircraft in a number of normal and non-normal flight maneuvers, such as mid-flight engine shutdown and restart, and power accelerations and decelerations. A Continental engineer recorded flight data on board. KLM, the Royal Dutch Airline, was the first airline to operate a passenger-carrying flight using biofuel. On 23 November 2009, a Boeing 747 flew, carrying a limited number of passengers, with one of its four engines running on a 50/50 mix of biofuel and kerosene.[23][24]

In June 2011, a Gulfstream G450 became the first business jet to cross the Atlantic Ocean using a blend of 50/50 biofuel developed by Honeywell derived from camelina and petroleum-based jet fuel.[25] The Dutch biofarming company Waterland International and a Japanese federation of farmers made an agreement in March 2012 to plant and grow camelina on 2000 to 3000 ha in Fukushima Prefecture. The seeds were to be used to produce biofuel, that could be used to produce electricity. According to director William Nolten, the region had a big potential for the production of clean energy. Some 800.000 ha in the region could not be used to produce food anymore, and after the nuclear disaster because of fears for contamination, the Japanese people refused to buy food produced in the region, anyway. Experiments would be done to find out whether camelina was capable of extracting radioactive caesium from the soil. An experiment with sunflowers had no success.[26]

Animal feed

Camelina has been approved as a cattle feed supplement in the US,[27] as well as an ingredient (up to 10% of the ration) in broiler chicken feed[28] and laying hen feed.[29] Camelina meal, the byproduct of camelina when the oil has been extracted, has a significant crude protein content. "Feeding camelina meal significantly increased (p < 0.01) omega-3 [fatty acid] concentration in both breast and thigh meat [of turkeys] compared to control group." Medical research indicates a diet abundant in omega-3 fatty acids is beneficial to human health.[30] Camelina oil has also been investigated as a sustainable lipid source to fully replace fish oil in diets for farmed Atlantic salmon, rainbow trout, and Atlantic cod.[31] However, various antinutritional factors are present in camelina oil meal and can affect its use as livestock feed.[32][33] The use of camelina meal for animal feed is only limited by the presence of glucosinolates.[34]

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency has approved feeding cold-pressed non-solvent extracted Camelina meal to broiler chickens at up to 12% inclusion.[35][36]

Use in Canada

Approximately 50,000 acres are currently cultivated in Canada. The Camelina Association of Canada projects Canada estimates that 1 to 3 million acres could be planted in the future. Several factors challenge the spread of camelina cultivation in Canada: it does not have government crop classification, and camelina meal is not approved as livestock feed. In early 2010, Health Canada approved camelina oil as a food in Canada.[37]

In 2014, camelina was included for the first time in Canada's Advance Payments Program (APP), commonly known as the cash advance program.[38]

Genetics

The first full genome sequence for Camelina was released on August 1, 2013, by a Canadian research team. The genome sequence and its annotation are available in a genome viewer format and enabled for sequence searching and alignment.[39] Technical details of Camelina's genome sequence were published on April 23, 2014 in the academic journal Nature Communications.[40]

In 2013 Rothamsted Research in the UK reported they had developed a genetically modified form of Camelina sativa that produced Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA).[41] EPA and DHA are omega-3 fatty acids which are beneficial for cardiovascular health. The main source of these omega-3 fatty acids is fish but supplies are limited and unsustainable.[42][43]

Agronomics

Cultivation

Camelina is a short-season crop (85–100 days) and grows well in the temperate climate zone in light or medium soils. Camelina is generally seeded in spring from March to May, but can also be seeded in fall in mild climates.[44]

A seeding rate of 3–4 kg/ha is recommended, with an row interval of 12 to 20 cm.[45] Seeding depth should not exceed 1 cm. With high seeding rates, these independently noncompetitive seedlings become competitive against weeds because of their density. The seedlings are early emerging and can withstand mild frosts in the spring. Minimal seedbed preparation is needed to establish camelina.[4]

Usually, camelina does not need any field interventions. However, perennial weeds may be difficult to control. Some specialized oilseed herbicides can be used on it. Also, camelina is highly resistant to black leg and Alternaria brassicae, but it can be susceptible to sclerotinia stem rot. No insect has been found to cause economic damage to camelina.[4] Camelina needs little water or nitrogen to flourish; it can be grown on marginal agricultural lands. Fertilization requirements depend on soils, but are generally low. It may be used as a rotation crop for wheat and other cereals, to increase the health of the soil.[46] Camelina can also show some allelopathic traits, and it can be grown in mixed crop with cereals or legumes.[47]

Camelina is harvested and seeded with conventional farming equipment, which makes adding it to a crop rotation relatively easy for farmers who do not already grow it.[48][49]

Seed yields vary depending on conditions and can reach 2700 kg/ha (2400 lb/acre).[4]

Cultivars

North America: 'Blaine Creek', 'Suneson', 'Platte', 'Cheyenne', 'SO-40', 'SO-50', 'SO-60'

Europe: 'Epona', 'Celine', 'Calena', 'Lindo', 'Madonna', 'Konto','D.Tagliafierro'

Invasive species

C. sativa subsp. linicola is considered a weed in flax fields. In fact, attempts to separate its seed from flax seeds with a winnowing machine over the years have selected for seeds which are similar in size to flax seeds, an example of Vavilovian mimicry.

See also

References

- "Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz". Plants of the World Online. Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- Reader's Digest Field Guide to the Wild Flowers of Britain. Reader's Digest. 1981. p. 48. ISBN 9780276002175.

- "The biology of Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz (camelina)". Canadian Food Inspection Agency. 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- D. T. Ehrensing; S. O. Guy (2008). "Camelina" (PDF). Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Extension Service. EM 8953-E. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- Francis, A. and Warwick, S. I. 2009. The biology of Canadian weeds. 142. Camelina alyssum (Mill.) Thell.; C. microcarpa Andrz. Ex DC.; C. sativa (L.) Crantz. Can. J. Plant Sci. 89: 791–810.

- Daniel Zohary and Maria Hopf, Domestication of plants in the Old World, third edition (Oxford: University Press, 2000), pp. 138f

- Megaloudi, Fragkiska (2006), Plants and Diet in Greece from Neolithic to Classic Periods: the archaeobotanical remains, Oxford: Archaeopress, ISBN 1-84171-949-8

- Jones, G.; Valamoti, S.M. (2005), "Lallemantia, an imported or introduced oil plant in Bronze Age northern Greece", Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 14 (4): 571–577, doi:10.1007/s00334-005-0004-z

- Dalby, Andrew (2003), Food in the ancient world from A to Z, London, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-23259-7

- "Camelina: A Promising Low-Input Oilseed".

- Gugel, R.K. and Falk, K.C. 2006. Agronomic and seed quality evaluation of camelina sativa in western Canada. Can. J. Pl. Sci. 86: 1047-1058

- Sampath, Anusha (2009), "Chemical Characterization of Camelina Seed Oil" https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/25894/PDF/1/play/

- Rainer Höfer (editor) Sustainable Solutions for Modern Economies, p. 208, at Google Books

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-09-18. Retrieved 2012-12-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Matthew McDermott "40,000 Gallons of Camelina Chosen for US Navy's Aviation Biofuel Test Program" Treehugger

- "Inside the Ring", Bill Gertz, Washington Times, 24 December 2009, page B1.

- "Air Force officials take step toward cleaner fuel, energy independence"

- Wright, Liz, "," navy.mil, 22 April 2010 3:30:00 p.m.

- "F-22 Raptor hits Mach 1.5 on camelina-based biofuel".

- Johnson, Andrew (September 2, 2011). "Blue Angels Use Biofuel at Patuxent Air Show.". United States Department of Defense (press release). Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- Lendon, Brad (September 3, 2011). "Blue Angels to fly on biofuels.". CNN. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- Bowen, Holley (July 29, 2011). "Air Force wants 50% use of biofuel by 2016.". Standard-Examiner. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- http://www.volkskrant.nl/economie/article1311609.ece/KLM_vervoert_passagiers_op_plantenbrandstof?source=rss

- Howell, Katie (November 23, 2009). "KLM Carries Passengers in Biofuel Test Flight". The New York Times.

- "Gulfstream G450 First Aircraft to Cross Atlantic Using Biofuels"

- (Dutch) NRC (14 March 2012)Dutch company grows bio/diesel in Fukushima

- "FDA approves camelina as cattle feed supplement"

- "FDA approves camelina meal as broiler chicken feed (02/17/09)"

- "Camelina Meal OKd To Be Included In Laying Hen Rations"

- "Feeding Camelina SATIVA to Meat Turkeys, Western Meeting of Poultry Clinicians and Pathologists"

- Hixson, SM.; Parrish, CC.; Anderson, DM. (2014). "Use of camelina oil to replace fish oil in feeds for farmed salmonids and Atlantic cod". Aquaculture. 431: 44–52. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2014.04.042.

- Heuzé V., Tran G., Lebas F., 2017. Camelina (Camelina sativa) seeds and oil meal. Feedipedia, a programme by INRA, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO. https://www.feedipedia.org/node/4254 Last updated on July 17, 2017, 16:42

- Russo R., Reggiani R. (2012) Antinutritive compounds in twelve Camelina sativa genotypes. American Journal of Plant Sciences, 3: 1408-1412

- Russo, R. and Reggiani, R. (2017) Glucosinolates and Sinapine in Camelina Meal. Food and Nutrition Sciences, 8, 1063-1073

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-01-17. Retrieved 2014-10-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Smart Earth Seeds".

- http://www.agriculture.gov.sk.ca/Default.aspx?DN=67a5b5a3-b4fc-402b-9ede-abcebb2b64b8%5B%5D

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-01-18. Retrieved 2015-01-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Camelina sativa Genome Project http://www.camelinadb.ca/index.html

- Kagale, Sateesh; Koh, Chushin; Nixon, John; Bollina, Venkatesh; Clarke, Wayne E.; Tuteja, Reetu; Spillane, Charles; Robinson, Stephen J.; Links, Matthew G.; Clarke, Carling; Higgins, Erin E.; Huebert, Terry; Sharpe, Andrew G.; Parkin, Isobel A. P. (2014). "The emerging biofuel crop Camelina sativa retains a highly undifferentiated hexaploid genome structure". Nature Communications. 5: 3706. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.3706K. doi:10.1038/ncomms4706. PMC 4015329. PMID 24759634.

- Ruiz-Lopez, N.; Haslam, R. P.; Napier, J. A.; Sayanova, O. (January 2014). "Successful high-level accumulation of fish oil omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in a transgenic oilseed crop". The Plant Journal. 77 (2): 198–208. doi:10.1111/tpj.12378. PMC 4253037. PMID 24308505.

- Simopoulos, Artemis P. and Cleland, Leslie G. (Editors) "Omega-6/Omega-3 Essential Fatty Acid Ratio: The Scientific Evidence" (World Review of Nutrition and Dietetics), Publisher: S Karger AG, 19 Sep 2003, ISBN 978-3805576406, Page 34

- Coghlan, Andy (4 January 2014) "Designed plant oozes vital fish oils"' New Scientist, Page 12, also available on the Internet at

- Hunter, Joel and Greg Roth 2010. Camelina Production and Potential in Pennsylvania, Agronomy Facts 72. College of Agricultural Sciences, Crop and Soil Sciences, Pennsylvania State University.

- Fiche technique, Agridea, Suisse

- http://www.renewableenergyworld.com/rea/news/article/2009/06/biofuel-could-lighten-jet-fuels-carbon-footprint-over-80-percent

- http://plants.usda.gov/plantguide/pdf/pg_casa2.pdf

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-03-29. Retrieved 2012-12-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-03-13. Retrieved 2012-12-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Camelina sativa. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Camelina sativa. |

- "Evaluation of Camelina sativa oil as a feedstock for biodiesel production", Industrial Crops and Products, Vol. 21 Issue 1 (January 2005), pp. 25-31

- USDA Plants Profile for Camelina Crantz

- USDA Plants Profile for Camelina microcarpa Andrz. ex DC. aka Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz ssp. microcarpa

- JAL Flight Brings Aviation One Step Closer to Using Biofuel

- First Green Supersonic Jet to Launch on Earth Day

- Jepson Manual Treatment

- "Camelina sativa". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

- Agricultural Research Service Researching Camelina as New Biofuel Crop

- Camelina Sativa: a Multiuse Oil Crop for Biofuel, Omega-3 Cooking Oil, and Protein/Oil Source for Animal Feed

- Biofuel-powered U.S. Air Force F-22 Raptor breaks sound barrier

- Camfeed Project