CIA headquarters shooting

On January 25, 1993, outside the George Bush Center for Intelligence, the CIA headquarters campus in Langley, Virginia, Pakistani national Mir Aimal Kansi killed two CIA employees in their cars as they were waiting at a stoplight and wounded three others.

| CIA headquarters shooting | |

|---|---|

| Part of terrorism in the United States | |

CIA headquarters, near the site of the shooting | |

| Location | Langley, Virginia, U.S. |

| Date | January 25, 1993 c. 8:00 am (EST) |

| Target | CIA employees |

Attack type | Shooting |

| Weapons | Norinco Type 56 semi-automatic rifle |

| Deaths | 2 |

| Injured | 3 |

| Victims | Frank Darling and Lansing H. Bennett |

| Perpetrators | Mir Aimal Kansi |

| Motive | U.S. foreign policy in Muslim countries |

Kansi fled the country and was placed on the FBI Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list, sparking a four-year international manhunt. He was captured by a joint FBI–CIA/Inter-Services Intelligence task force in Pakistan in 1997 and rendered to the United States to stand trial. He admitted shooting the victims, was found guilty of capital and first-degree murder, and was executed by lethal injection in 2002.

Background

Mir Aimal Kansi (or Mir Qazi) was born in Quetta, Balochistan, Pakistan, either on February 10, 1964, or January 1, 1967.[1] He entered the US in 1991, taking a substantial sum of cash he had inherited on the death of his father in 1989. He travelled on forged papers he had purchased in Karachi, Pakistan, altering his last name to "Kansi", and later bought a fake green card in Miami.[2] He stayed with a Kashmiri friend, Zahed Mir,[3] in his Reston, Virginia, apartment, and invested in a courier firm for which he also worked as a driver.[4] This work would be decisive in his choice of target: "I used to pass this area almost every day and knew these two left-turning lanes [were] mostly people who work for CIA."[2]

According to Kansi, he first thought of attacking CIA personnel after buying a Chinese-made AK-47 from a Chantilly gun store. The plan soon became "more important than any other thing to [him]."[2]

Shootings

At around 8 a.m. on January 25, 1993, Kansi stopped a borrowed brown Datsun station wagon[5] behind a number of vehicles waiting at a red traffic light on the eastbound side of Route 123, Fairfax County.[6] The vehicles were waiting to make a left turn into the main entrance of CIA headquarters. Kansi emerged from his vehicle with an AK-47 semi-automatic rifle, and proceeded to move among the lines of vehicles, firing a total of 10 rounds into them,[7] killing Lansing H. Bennett, 66, and Frank Darling, 28. Three others were left with gunshot wounds.[4] Darling was shot first and later received additional gunshot wounds to the head after Kansi shot the other people. According to a CIA release, "all the victims were full-time or contract employees with the agency." No other details were revealed.[8]

During his later confession, Kansi said that he only stopped firing because "there wasn't anybody else left to shoot", and that he only shot male passengers because, as a Muslim, "it would be against [his] religion to shoot females".[4] He was surprised at the lack of an armed response: "I thought I will be arrested, or maybe killed in a shootout with CIA guards or police."[2]

Kansi climbed back into his vehicle and drove to a nearby park. After 90 minutes of waiting, he realized that he was not being actively sought and drove back to his Reston apartment.[4] At the time, reports said police were looking for a white male in his twenties, and the shooting was not thought to be directly connected to the CIA.[9] He hid the rifle in a green plastic bag under a sofa, went to a McDonald's to eat, and booked into a Days Inn for the night. He learned from CNN news reports that police had misidentified his vehicle and did not have his license plate number.[3] The next morning, he took a flight to Quetta. Kansi stated his motive in a prison interview with CNN affiliate WTTG Fox 5: "I was real angry with the policy of the U.S. government in the Middle East, particularly toward the Palestinian people."[10]

Investigation

An investigative task force (named "Langmur" for "Langley murders") was drawn together from both the FBI and local Fairfax County police. They began sifting through recent AK-47 purchases in Maryland and Virginia—there had been at least 1,600 over the previous year alone. Kansi's name was on the sales slip from a gun store in Chantilly, where he had exchanged another gun for the AK-47[3] just three days before the shootings.[4]

This information provided the first solid lead in the investigation when Kansi's roommate, Zahed Mir, reported him missing two days after the shootings.[4] He also told police how Kansi would get angry watching CNN reports of attacks on Muslims[3]–in particular, Kansi would later cite the US attacks on Iraq, Israeli killings of Palestinians, and CIA involvement in Muslim countries.[2][4] Although Mir did not think much of it at the time, Kansi had said he wanted to do "something big", with possible targets, the White House, the Israeli Embassy, and the CIA.[3]

A police search of Kansi's apartment turned up the hidden AK-47 under the couch. Ballistics tests confirmed it was the weapon used in the shootings, and Kansi became the chief suspect of the investigation.[3] He was listed as one of the FBI Ten Most Wanted Fugitives.[11] The search focused on Pakistan, and agents spent the next four years following hundreds of leads, taking them as far afield as Thailand, but to no avail.[3] Kansi would later reveal that he had spent this time being sheltered by fellow Pashtun tribesmen, in the border regions of Afghanistan, making only brief visits to Pakistan.[2][4]

Capture and rendition

In May 1997, an informant walked into the U.S. consulate in Karachi and claimed he could help lead them to Kansi. As proof, he showed a copy of a driver's license application made by Kansi under a false name but bearing his photograph. Apparently, the people who had been sheltering Kansi were now prepared to accept the multimillion-dollar reward offer for his capture. Other sources claim they were pressured by the Pakistani government. Kansi stated "I want to make it clear (that) the people who tricked me ... were Pushtuns, they were owners of land in the Leghari and Khosa clan areas in Dera Ghazi Khan, but I will never name them."[12]

Kansi was near the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, so the informant was told to lure Kansi into Pakistan where he could be more easily apprehended. Kansi was tempted with a lucrative business offer—smuggling Russian electronic goods into Pakistan—which brought him to Dera Ghazi Khan, in the Punjab province of Pakistan, where he checked into a room at Shalimar Hotel.[12]

At 4 am on the morning of June 15, 1997, an armed team of FBI agents, working with the Pakistani ISI, raided Kansi's hotel room to arrest him. His fingerprints were taken at the scene, confirming his identity.

There is some dispute over where Kansi was taken next—U.S. authorities claim it was a holding facility run by Pakistani authorities,[4] while Pakistani sources claim it was the U.S. embassy in Islamabad[12]–before being flown to the U.S. on June 17 in a C-141 transport.[4][13]

During the flight, Kansi made a full verbal and written confession to the FBI.[4]

Kansi's extrajudicial rendition was controversial in Pakistan—no formal request for his extradition was made, and no extradition proceedings were initiated.[13] U.S. authorities would later assert that the rendition was legal under an extradition treaty signed with the UK, before Partition when India was under colonial rule.[4] Kansi argued against his rendition in court but his assertions were found to have no basis in law. The Court wrote:

...the treaty between the United States and Pakistan contains no provision that bars forcible abductions, nor does it otherwise 'purport to specify the only way in which one country may gain custody of a national of the other country for the purposes of prosecution.' Id. at 664. Nor does the treaty provide that, once a request for extradition is made, the procedures outlined in the treaty become the sole means of transferring custody of a suspected criminal from one country to the other. Finally, because Kansi was not returned to the United States via extradition proceedings initiated under the Extradition Treaty between the United States and Pakistan, Kansi's reliance upon United States v. Rauscher did not avail him.[14]

Trial

On February 16, 1993, Kansi, then a fugitive, was charged with the capital murder of Darling, murder of Bennett, and three counts of malicious wounding for the other victims, along with related firearms charges.

Kansi was tried by a Virginia state court jury over a period of ten days in November 1997, on a plea of not guilty to all charges. During the trial, the defense introduced testimony from Dr. Richard Restak, a neurologist and also a neuropsychiatrist, that Kansi was missing tissue from his frontal lobes, a congenital defect that made it hard for him to judge the consequence of his actions. This testimony was re-iterated by another psychiatrist for the defense based upon independent examination. The jury found him guilty, and fixed punishment for the capital murder charge at death.[4]

On February 4, 1998, Kansi was sentenced to death for the capital murder of Darling, who was shot at the beginning of the attack and again after the other victims had been shot. Among his other punishments were a life sentence for the first-degree murder of Bennett, multiple 20-year sentences for the malicious woundings, and fines totaling $600,000.[4]

Possible vendetta

Days before Kansi's conviction in November 1997, four U.S. oil executives and their Pakistani taxi driver were shot dead in Karachi, in what has been described as a deliberate response to Kansi's guilty verdict.[15][16]

Execution

Kansi was executed by lethal injection on November 14, 2002, at Greensville Correctional Center in Jarratt, Virginia,[17] and his body was repatriated to Pakistan.

Victims

The two fatalities resulting from Kansi's attack were Lansing H. Bennett M.D., 66, and Frank Darling, 28, both CIA employees. Bennett, with experience as a physician, was working as an intelligence analyst assessing the health of foreign leaders.[18] Darling worked in covert operations.[3]

The three people wounded in the attack were Calvin Morgan, 61, an engineer; Nicholas Starr, 60, a CIA analyst; and Stephen E. Williams, 48, an AT&T employee.[3]

Memorials

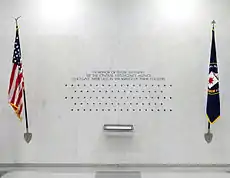

Central Intelligence Agency memorial wall

Bennett and Darling were memorialized as the 69th and 70th entries on the CIA's "memorial wall" of stars in the foyer of the Langley headquarters building, although President Clinton, in an address to the CIA, attributed the two individuals as the 55th and 56th stars.[19]

Route 123 Memorial

The Route 123 Memorial, consisting of a granite wall and two benches facing each other near the site of the shooting, is dedicated to Bennett and Darling.[20] This memorial is illuminated at night. The memorial is not at the exact location of the shooting due to traffic reasons.

An inscription reads:

In Remembrance of Ultimate Dedication to Mission Shown by Officers of the Central Intelligence Agency Whose Lives Have Been Taken or Forever Changed by Events at Home and Abroad.

Dedicato Par Aevum

(Dedicated to Service)

May 2002

The memorial was dedicated May 24, 2002.[20]

Lansing Bennett Forest

A forest was renamed in Bennett's honor—the Lansing Bennett Forest in Duxbury, Massachusetts, where he was formerly chair of the Duxbury Conservation Commission.[21]

Bennett is interred in the Quivet Neck Cemetery, off Route 6A, East Dennis, Massachusetts, along with his brother and parents in a family plot.

See also

- 2010 Pentagon shooting: A similar shooting where a gunman shot two police officers at the military intelligence headquarters.

- List of incidents of political violence in Washington, D.C.

References

- "Mir Aimal Kansi". FBI. October 22, 1996. Archived from the original on October 22, 1996. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- Stein, J. "Convicted assassin: 'I wanted to shoot the CIA director'", Salon, January 22, 1998.

- Davis, P. & Glod, M. "CIA Shooter Kansi, Harbinger of Terror, Set to Die Tonight", The Washington Post, November 14, 2002.

- Justice A. Christian Compton,"Virginia Supreme Court Opinion on Mir Aimal Kansi". Archived from the original on February 7, 2007. Retrieved February 7, 2007., November 6, 1998.

- Bill Miller. "Gunsmith Says Tip on Kansi Went Unheeded; ATF Disputes Employee's Account", Washington Post, February 12, 1993

- Steve Coll, "Ghost Wars", New York: Penguin Books, 2004, pp. 246–247

- Benjamin, Daniel & Steven Simon. "The Age of Sacred Terror", 2002

- B. Drummond Ayres, Jr. (January 26, 1993). "Gunman Kills 2 Near C.I.A. Entrance". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- =https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1993-01-26-mn-2002-story.html

- ARCHIVES CNN Pakistani man executed for CIA killings November 15, 2002

- "FBI-Ten Most Wanted Fugitive-Mir Aimal Kansi". Archived from the original on October 22, 1996. Retrieved April 10, 2017.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Hasan, K. "How Aimal Kasi was betrayed Archived January 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine", Daily Times (Pakistan), June 23, 2004.

- Khan, R. "In search of truth", Dawn, November 24, 2002.

- "FindLaw's United States Fourth Circuit case and opinions". Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- Knowlton, B. "Americans Abroad Face a Rising Risk of Terrorism", International Herald and Tribune, November 21, 1997.

- "Jury Murderer of CIA workers deserves death". CNN. November 14, 1997. Archived from the original on October 7, 2012. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- Glod, M. & Weiss, E. "Kansi Executed For CIA Slayings, The Washington Post, November 15, 2002.

- "Lansing Bennett, Physician Slain Outside CIA", The Washington Post, January 27, 1993.

- Remarks from President to CIA employees

- "CIA virtual tour". Archived from the original on September 11, 2007. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- MA, Duxbury. "Duxbury, MA - Lansing Bennett Forest". Archived from the original on November 8, 2016. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- "Revered - but for what?". May 18, 2010. Retrieved November 7, 2016.