Brucella canis

Brucella canis is a gram-negative proteobacterium in the family Brucellaceae that causes brucellosis in dogs and other canids. B. canis is rod-shaped or a coccus, and is oxidase, catalase, and urease positive.[1] The species was firstly described in United States in 1966 where mass abortions of beagles were documented.[2] The disease is characterized by epididymitis and orchitis in male dogs, endometritis, placentitis, and abortions in females, and often presents as infertility in both sexes. Other symptoms such as inflammation in the eyes and axial and appendicular skeleton; lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly, are less common.[3] Humans can be also infected, but occurrences are rare.[3] Although there has been an increase in the international movement of dogs, Brucella canis is still very uncommon.[4]

| Brucella canis | |

|---|---|

| |

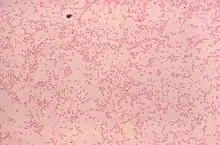

| Gram-stained photomicrograph depicting numerous gram-negative Brucella canis bacteria | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Proteobacteria |

| Class: | Alphaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Rhizobiales |

| Family: | Brucellaceae |

| Genus: | Brucella |

| Species: | B. canis |

| Binomial name | |

| Brucella canis Carmichael & Bruner, 1968 | |

B. canis is a zoonotic organism. Signs of this disease are different in both genders of dogs; females that have B. canis infections face an abortion of their developed fetuses. Males face the chance of infertility, because they develop an antibody against the sperm. This may be followed by inflammation of the testes which generally settles down a while after. Symptoms do not only include testicular inflammation, infertility in males, and abortion in females. Another symptom is the infection of the spinal plates or vertebrae, which is called diskospondylitis.

Treatment for B. canis is very difficult to find and often very expensive. The combination of minocycline and streptomycin is thought to be useful, but it is often unaffordable. Tetracycline can be a less expensive substitute for minocycline, but it also lowers the effect of the treatment.

Brucella canis is a gram-negative coccobacillus bacteria.[5] B. canis can be found in both pets and wild animals and lasts the lifespan of the animal it has affected. It is generally spotted in the animal's reproductive organs. This infection usually causes the animal to spontaneously abort a fetus and can also cause an animal to become sterile.[6]

B. canis is relatively easy to prevent in dogs. There is a simple blood test that can be done by a veterinarian. Any dog that will be used for breeding or has the capability to breed should be tested. Although rare, humans can contract the infection. It is unlikely, but most common in dog breeders, those in laboratories dealing with the bacteria, or people who are immunocompromised.[7]

B. canis is difficult to treat. Long term antibiotics can be given but usually results in a relapse. Spaying and neutering can be effective, and frequent blood tests are recommended to monitor progress. Dogs in kennels that are affected by B. canis are usually euthanized for the protection of other dogs and the humans caring for them.[8]

References

- Mantur BG, Amarnath SK, Shinde RS (July 2007). "Review of clinical and laboratory features of human brucellosis". Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology. 25 (3): 188–202. doi:10.4103/0255-0857.34758. PMID 17901634.

- Morisset R, Spink WW (November 1969). "Epidemic canine brucellosis due to a new species, brucella canis". The Lancet. 2 (7628): 1000–1002. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(69)90551-0. PMC 2441019. PMID 4186949.

- Brower A, Okwumabua O, Massengill C, Muenks Q, Vanderloo P, Duster M, Homb K, Kurth K (September 2007). "Investigation of the spread of Brucella canis via the U.S. interstate dog trade". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 11 (5): 454–458. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2006.12.009. PMID 17331783.

- Cosford, Kevin L. (2018). "Brucella canis: An update on research and clinical management". The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 59 (1): 74–81. PMC 5731389. PMID 29302106.

- “Brucellosis: Brucella Canis Contagious Abortion, Undulant Fever.” http://Www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/Pdfs/brucellosis_canis.Pdf, The Center for Food Security & Public Health, 28 May 2018, www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/pdfs/brucellosis_canis.pdf.

- Brucellosis Fact Sheet. State of California California Department of Public Health Health and Human Services Agency Division of Communicable Disease Control, July 2012, www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/CDPH%20Document%20Library/BrucellosisFactSheet.pdf.

- Brucellosis FAQs for Dog Owners. Georgia Division of Public Health in Partnership with the Georgia Department of Agriculture Office of the State Veterinarian, and the University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine, 13 June 2006, agr.georgia.gov/Data/Sites/1/media/ag_animalindustry/animal_health/files/caninebrucellosiskennelanowner.pdf.

- Canine Brucellosis and Foster-Based Dog Rescue Programs. Minnesota Department of Health, Jan. 2016, www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/brucellosis/canine.pdf.

External links

- Brucella canis genomes and related information at patricbrc.org, a Bioinformatics Resource Center funded by NIAID