British United Shoe Machinery

British United Shoe Machinery (BUSM) Ltd. with head office in Leicester, England, was formed around the turn of the 20th century as a subsidiary of United Shoe Machinery Company of the US, becoming part of a group which for most of the 20th century was the world's largest manufacturer of footwear machinery and materials, exporting shoe machinery to more than 50 countries.[1] After two takeovers and a BUSM-based management buyout the USM group became headquartered in Leicester[2] until entering administration in 2000.

US Founders of British United Shoe Machinery. | |

| Industry | Footwear machinery and materials |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1899 |

| Founder | Charles Bennion |

| Defunct | 2000 |

| Headquarters | Leicester, England |

In the 1960s and 1970s, it was Leicester's biggest employer employing more than 4,500 locally and 9500 worldwide.[1] Most of the workforce was recruited via an apprentice scheme which trained a large proportion of Leicester's engineers.[1][3] The company had "a respected reputation for technical innovation and excellence",[1] between 1898 and 1960, it developed and marketed nearly 800 new and improved shoe machines and patented more than 9,000 inventions, at one time employing 5% of the UK's patent agents.[4]

The collapse of the company in October 2000 destroyed the pensions of the workers. Their story became "one of the most vivid examples of what can go wrong with..Private Equity".[5] The company subsequently went into administrative receivership and was the subject of a management buyout. This new company itself went into administration in September 2006. In November 2006 a new independent company, Advent Technologies Ltd, was formed by former workers of BUSM providing technical support, advice and spare parts for the range of BUSM machinery.

Formation

During the nineteenth century, many shoe manufacturing processes were mechanised and the resulting numerous small factories merged over time. In 1882, Tomlin and Sons of Leicester, cutlery and shoe machinery manufacturer[6] and William Pearson of Leeds were acquired by Merry and Bennion which by the mid-1890s was a leading supplier of UK shoe machinery. Renamed Pearson and Bennion, in 1898 it moved to the new Union Works factory on Ross Walk near Belgrave Road Leicester.

In February 1899, the 3 major US shoe machinery companies, Goodyear Machinery Company, Consolidated Hand Lasting Machine Company and McKay Shoe Machinery Company merged to form United Shoe Machinery (USM).[7]

Pearson and Bennion's managing director, Charles Bennion went to Boston to negotiate a merger with USM and the company which would eventually become BUSM (British United Shoe Machinery) was incorporated in October 1899 with the Union Works factory as its headquarters.[8][9] The 1st years accounts dated 31 May 1900, showed 200 employees, profits of £16500 and £300,000 capital.[10] A further 10 acres (40,000 m2) of land was purchased in 1901 from the Belgrave Road Cricket and Bicycle Grounds, the former home of both Leicester Fosse FC and Leicester Tigers.[11]

Expansion and business strategy

The new British United Shoe Machinery was uniquely able to supply a footwear manufacturer with all machinery needs. By 1908 the company's technical innovations were sufficiently noteworthy to attract a visit from the British Association for the Advancement of Science.[12] The company followed US policy of leasing machinery, which had the advantage of minimising entry costs for new customers. Lease restrictions however caused much resentment and there was particularly strong opposition from Northampton manufacturers who feared it was becoming a monopoly.[4]

Despite the huge increase in demand for military footwear, World War I saw over 800 of the highly skilled workers joining the armed forces. Under the Munitions of War Act 1915 passed in response to the Shell Crisis of 1915, the company became a "Controlled Establishment" with workers pay and conditions very tightly regulated by the Ministry of Munitions. BUSM's expertise in precision engineering led to orders for a range of military equipment including Naval gun mountings and aero engine parts as well as shells and fuzes.[13]

Shoe components

The 1920s saw the company diversify into shoe components including those made from synthetic materials,[14] a process that continued after World War II and helped reduce the effects of the Economic cycle.[15]

Great Depression and WW2

The company flourished throughout the Great Depression and the Second World War.[9] By 1930 it had 12 UK sales and service branches, a valuable asset for customers before reliable car travel was available. Issued capital was seven times greater than 1899 and profits were ten times greater.[16]

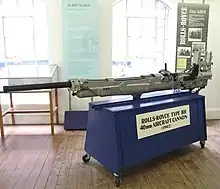

WW2 saw a much higher percentage of BUSM's precision engineering capacity switched to manufacturing arms than in WW1. Products included Naval gun sights, Besa machine gun and the technically very demanding precision cast wheelhouse for the Rolls-Royce Merlin aero engine.[17] BUSM also worked extensively on aspects of the development and was the main sub-contractor for the Rolls-Royce 40mm Cannon which was originally originally intended for mounting in aircraft, especially for use in the anti-tank role. No operational use was made of the experimental aircraft fitted with this gun, but the Royal Navy saw its potential when fitted to Motor gunboats. BUSM was the main subcontractor for several hundred examples built for the navy.[18]

Post war, BUSM was an early user of numerical control machines in its manufacturing with the prototype Kearns horizontal boring machine now in Manchester Institute of Technology museum being installed in 1949.[12]

Monopoly and breakup

In December 1947 the US government brought proceedings against USM, the parent company of BUSM, alleging a breach of the Sherman Antitrust Act in that the company had been a monopoly since 1912.[9] A "trial of prodigious length" followed but although the verdict went against USM, the corporation wasn't broken up and the judgement and remedy was confirmed by the Supreme Court in 1954. The government renewed its complaint in 1967 but although the District Court ruled nothing had changed, this time the Supreme Court ordered USM to be broken up. It was required to divest a substantial part of its business and change its leasing strategy over a 10-year period. The sell-off raised $400 million but attempts at diversification failed to generate enough money and in 1976 the company, heavily in debt, was bought by Emhart Corporation, now Emhart Teknologies,[9] an organisation half its size.[19]

Decline, partial recovery and return to private ownership

Though BUSM won a Queen's Award for Export in 1971, the 1970s saw the company's advantage in complex production machinery eroded, as off the shelf hydraulics, pneumatics and electronics replaced many mechanical components, reducing the cost of entry to new competitors. The already strong German and US competition and the growing Italian shoe industry was joined by competition from Korea and Taiwan both using cheaper labour and all started to source local machinery. BUSM itself initiated design simplification offering Injection moulding and cementing as an alternative to stitching.[20]

In 1983 the Department of Trade and Industry sponsored a transformation of BUSM's manufacturing processes with what was one of Europe's most advanced Flexible manufacturing systems, four KTM numeric control machining centres were installed for discrete component manufacturing. BUSM's unique application of FMS to highly varied, low volume work remained in use for 15 years.[21]

The company also developed computer control machinery claiming world leadership of microprocessor controlled shoe machinery and 75% of the world market by the end of the 80s.[22]

A long-term research project, starting in the late 1970s and involving universities and a polytechnic, was to use machine vision to automate the production of shoe uppers.[23][24] The idea was that after the components of shoe uppers were cut by multiple operators they would be placed on a conveyor system which would carry the pieces through automatic machines. These machines would use vision systems to identify the components arriving in any order and orientation, and then decorate and join them as required. The first and only of these machines with vision to go on sale, in the mid 1990s, was the MPCS AUTOSCAN which produced decorative stitching on shoe upper components.[25] However, although the vision system which used a T800 Transputer was successful, accurately manipulating the shoe upper components (which can range from stiff and curled to floppy and intricately shaped) was always problematic.

By 1986 Emhart's business strategy had changed to avoid highly cyclical industries like footwear. After 18 months negotiation, "Britain’s largest ever Management buyout" led by John Foster[26] purchased the whole worldwide shoe machinery business, excluding materials, at a cost of £80M.[27] This included shoe machinery manufacturing plants in England, Germany, the US, Brazil and Taiwan.[2]

Chris Price, a former BUSM graduate apprentice who became Research and Development Manager and eventually rose to the board rejoined the MBO as Technical Director.[28]

Finance Director Richard Bates said "We have broken free of the shackles of a multi-product group run on financial criteria, so we can now run a single industry business".[2]

Under Emhart's ownership, the old Union Works was demolished and the site, the sports club and the Mowmacre Hill sports ground were sold off.[29]

"BU's renewed vigour" became apparent when in 1989, it was one of only three UK companies to win both a Queen's Award for Technology and a Queen's Award for Exports. Exports accounted for 60% of the business.[30]

In 1990 BUSM bought the shoe materials company Texon from Emhart's owners Black & Decker for around $125M, doubling turnover to £200m and increasing the workforce to around 3000.[31]

USM-Texon as the group became known, transferred workers to its new pension scheme.[32] USM-Texon was in a unique position, the only one in the world manufacturing both shoe materials and machinery.

Now focusing on materials, it opened a factory in Foshan South China in 1993 and Chennai, India in 1994[31] and planned to float on the London Stock Exchange the following year.[33]

Chris Price's achievements were recognised as he became the 1995 president of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, the youngest for 100 years.[28]

Rolls-Royce type BH 40mm Aircraft Cannon (1942) on display at the Silk Mill Museum, Derby, in 2010.

Rolls-Royce type BH 40mm Aircraft Cannon (1942) on display at the Silk Mill Museum, Derby, in 2010. Shoe machinery on the USM-Texon stand at the international fair at Pirmasens, Germany, late 1990s

Shoe machinery on the USM-Texon stand at the international fair at Pirmasens, Germany, late 1990s Panorama of Shoe machinery on the USM-Texon stand at the international fair at Pirmasens, Germany, late 1990s

Panorama of Shoe machinery on the USM-Texon stand at the international fair at Pirmasens, Germany, late 1990s Elements of the Crispin shoe CAD/CAM section of the USM-Texon stand at the fair at Pirmasens, Germany, late 1990s

Elements of the Crispin shoe CAD/CAM section of the USM-Texon stand at the fair at Pirmasens, Germany, late 1990s MPCS AUTOSCAN vision-controlled automatic stitcher at the Royal Society, London

MPCS AUTOSCAN vision-controlled automatic stitcher at the Royal Society, London MPCS AUTOSCAN vision-controlled automatic decorative stitcher for shoe-upper components

MPCS AUTOSCAN vision-controlled automatic decorative stitcher for shoe-upper components

Failed Flotation, Apax Partners and pension collapse

Initial optimism turned sour and the flotation was cancelled, leading to its acquisition in 1995 by Venture Capitalists Apax Partners Corporate Finance Limited for £131M.[33]

John Foster retired in 1996 and received an OBE.[26]

Apax appointed Dr Neil Coutts as BUSM Chief Executive and later that year, the company completed its largest ever shoe factory installation; a factory in Vietnam which employed 7000 people.[33]

In 1997, USM-Texon announced they would demerge into British United Shoe Machinery and Texon UK "in order to increase the focus on their respective businesses."[33]

The award-winning Research and Development department's budget was "promptly cut.. by 60 per cent"[5] and Chris Price left for Rolls Royce where he eventually became an Executive Vice President.[34]

On completion of the demerger in 1998,[35] Coutts joined Apax owned Dexion[36] which went into receivership in 2003, leaving workers worse off than if they "had never joined the Dexion scheme."[37] Coutts remained a BUSM director, others included Jon Moulton, the Apax former head of Buyouts and Roger Earl.[38] Earl was to head the 2000 Management buyout in which Moulton was the majority shareholder and controlling interest.[39] Tim Wright of Apax was a common director of both BUSM and Texon's parent company.[40]

The company failed to thrive. In February 2000, the Crispin shoe CAD/CAM product division, a key IT asset, was sold by installments to Texon, allegedly at a knock down price.[5] The company continued to manufacture machinery, producing a stock pile which remained unsold until purchased from the Administrator by the management buy out company.[5] On 14 September 2000 the USM-Texon scheme transferred assets into the BUSM plan set up in March 1999. On 30 September a new valuation of this scheme showed it needed payment of £2.3m to meet Guaranteed Minimum Pension. Around 1 October, the third and final installment for Crispin was paid and on 4 October the bank put in Administrators.[5]

The failure caused little initial surprise or anger as shop floor Convenor and Pensions Trustee Bob Duncan had long assured workers that whatever happened to the Company their pensions were safe. Unfortunately and unknown to Duncan, the official advice on which this was based on simply wasn't true. As one of four Judicial Review litigants,[41] Duncan played a key part in Dr Ros Altmann's eventually successful Pensionstheft campaign. Invited to give evidence before the Public Administration Select Committee, Duncan blamed the government's misleading information. The Committee agreed.[42]

Once the Independent Trustee revealed the full extent of the pension loss in January 2002, Apax's alleged role in the collapse of the company came under scrutiny. Three separate complaints were made, all rejected on the grounds of jurisdiction leading Dr Ashok Kumar MP to tell Parliament that "Some serious joined-up thinking is needed on all these issues".[43] Duncan complained to OPRA but this organisation at that time could only investigate alleged wrongdoing by Trustees and notoriously lacked effectiveness[44] The regulator did say that the complaint contained information which "might be of interest to the DTI"[43] though a dossier submitted via Patricia Hewitt under Section 447 the Companies Act 1985 was rejected as the DTI could not investigate unincorporated bodies such as pension schemes, an investigation was unlikely to be effective, and complaints were best handled by the Pensions Ombudsman.[43][45]

Workers then complained to the Pensions Advisory Service and then to the Pensions Ombudsman. Apax' solicitors immediately challenged his right to investigate a share holder[46] under the PENSION SCHEMES ACT 1993, PART X[47] which limits jurisdiction to scheme trustees, managers or employers. This forced the Ombudsman to drop the lead case and to advise others that "any complaints against directors of Texon or Apax would be outside the Pensions Ombudsman's jurisdiction as they are not employers, trustees, managers, or administrators in relation to the BUSM Pension Plan".[48] Following advice from Ros Altmann workers went to see their MPs, and also found strong support from both National and local newspapers. They blamed Apax for having engineered the collapse[49] Edward Garnier named Sir Ronald Cohen and asked what discussions "ministers have had..about the collapse of the pension scheme".[50] Patricia Hewitt, the Health Secretary and a local MP also called for an enquiry.[51] In a letter to Alan Johnson MP, the Department of Trade and Industry minister, she recommended "that the Companies Investigation Branch should look at the concerns raised by my constituent. It may be that the problem falls between DTI and OPRA; but it is clearly important that such serious allegations are properly investigated."[52] The response merely referred to the CIB investigation in 2002 and its conclusion that "the issues raised were best dealt with by other bodies."[53] Garnier raised the issue again with the new Minister for Pensions Reform Stephen Timms citing the "mysterious circumstances" under which the pensions disappeared. Timms agreed to "look into" the complaints saying that "in recent years, there have been too many instances of that kind."[54][55] The press expected a proper enquiry.[55][56] In September 2005 Timms wrote back to Edward Garnier saying that the Pensions Regulator had found no breach of Pensions Regulations, though the Pensions Ombudsman was still investigating two complaints.[57] Neither organisation of course could investigate Apax so Timms' "investigation" revealed nothing new.

Aftermath

The Budget of March 2007 included the news that workers would receive most of their expected pensions from an improved Financial Assistance Scheme. A long-standing meeting arranged by Loughborough MP Andy Reed with minister James Purnell took place shortly afterwards following which, both BBC and ITV regional news led with interviews of those attending.[58] For some, it was too late. George Curtis, a Parkinson's sufferer was forced to work beyond 55, the age of ill health retirement at BUSM. ITV showed Curtis at work and followed up later when, thanks to Altmann's campaigning, he was awarded a pension at 60.

Sir Ronald Cohen and Apax insist all questions have been addressed but in the absence of any meaningful enquiry, it was left to MPs, Ros Altmann, and the media to comment on Apax's behaviour.

Ros Altmann described BUSM as "one of the worst cases of scheme wind-ups that I have seen. ..the actions of the former owners - Apax - have been immoral."[5]

MP Ashok Kumar said, "I think these people needed flogging. I feel so angry on behalf of decent upright citizens robbed of their basic human rights. ...'These are greedy, selfish, capitalists who live on the backs of others. In a modern democracy these people have been robbed"[5]

BUSM Factory Site

In 2007 a planning application was made for 1210 houses on the former site on Ross Walk[59] by Trafalgar Global Ltd. The construction of new homes commenced in 2010 with the first residential occupiers of site moving there in 2011. The first phase of the development was completed in 2011 by Westleigh Developments Ltd. The chimney was demolished in January 2012.[60]

BU History Group lottery project

In 2012 the National Lottery awarded funds to record the social history of BUSM -described as a "powerhouse of British manufacturing" -via a website, DVD and book. [61][62] Founder member of the BU History Group, Burt McNeill, reflecting on the fact that BUSM operated throughout the twentieth century, described the project as a chance to tell, not just a part of Leicester's history, but of British industrial history.[62]

References

- Howie, Iain (1999). USM Serving the Shoemaker for 100 years. Shoe Trades Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 0-9536531-0-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howie 1999, p. 117

- Howie 1999, p. 90.

- Howie 1999, p. 23

- Nick Mathiason (10 June 2007). "Private equity stole our pensions". Observer Newspapers. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- "The National Archives". The National Archives. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- "USM in Beverly USA Background and history". Cummings Properties. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- Howie 1999, pp. 7–11

- "United States v. United Shoe Machinery Corporation, District Ct. of the U.S., District of Mass., 1949-1952 Finding Aid". Harvard Law School. July 2004. Archived from the original on 10 December 2012. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- Howie 1999, p. 19

- "Short sporting lifetime". leicester mercury. 1 February 2010. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- Howie 1999, p. 105

- Howie 1999, p. 47

- Howie 1999, p. 53

- Howie 1999, p. 89

- Howie 1999, p. 51

- Howie 1999, p. 85

- Birch, David (2000). Rolls-Royce Armaments. Derby: Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust. p. numerous. ISBN 1-872922-15-5.

- Howie 1999, p. 99

- Howie 1999, p. 103

- Howie 1999, p. 111

- Howie 1999, p. 109

- GB patent 2067326B, "Workpiece identification apparatus", published 1983-03-09, assigned to The British United Shoe Machinery Company Limited

- US patent 4862377, David C. Reedman, Clive Preece & Clive Preece, "DETECTING WORKPIECE ORIENTATION AND TREATING WORKPIECES WITHOUT REORIENTING", published 1989-08-29, assigned to British United Shoe Machinery Ltd.

- Price, F Christopher (October 1995). "Engineering success using teamwork". Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. 209 (5): 337–340. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- "Mr John Foster, OBE, Hon LLD". University of Leicester. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- Howie 1999, p. 115

- "Institution of Mechanical Engineers' heritage website President Frank Christopher Price 1995". Archived from the original on 26 August 2009. Retrieved 7 March 2010.

- Howie 1999, p. 114

- Howie 1999, p. 121

- Howie 1999, p. 124

- "Texon Pension Trustees Ltd v USM Texon Ltd, Case HC 99 01817". 7 December 2000. p. 1. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- Howie 1999, p. 125

- "Engineering executive's delight at OBE honour". Harborough Mail. 3 January 2008. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- "Article: Dexion poised for 350m pound Nordic merger". The Scotsman. 23 September 1998. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012.

- "Dexion merger". The Independent. 23 September 1998. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- "Michael paid his pension for 34 years. Then he lost everything". The Daily Telegraph. 7 October 2006. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- Company House Accounts 363's Annual Return USM Group Holdings Ltd Company No 3473337 11 November 1999

- Company 4479445 British United Shoe Machinery Directors Reporte and Consolidated statements for the year ended 31 December-2004

- Company 3473337 USM Group Holdings Reports and Accounts 31 December-1998 section 22

- The Hon Mr Justice Bean (21 February 2007). "Case CO/4927/2006 Citation no:[2007]EWHC 242(Admin)" (PDF). The Royal Courts of Justice. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- House of Commons Public Administration Select Committee (20 July 2006). "The Ombudsman in Question:the Ombudsman's report on pensions and its constitutional implications" (PDF). The Stationery Office Limited. pp. 13–14. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Deferred Pensions, Dr Ashok Kumar: Column 235WH". Hansard. 17 January 2006. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- "MPs savage pensions watchdog". The Daily Telegraph. 7 May 2003.

- email from David McKinlay, dated July 2003 in response to complaint made in October 2002

- Dickson Minto WS letter to Carl Monk, Investigating Assistant, Office of the Pensions Ombudsman, Ref M00840/cm, dated 20 January-2003

- "PART X INVESTIGATIONS: THE PENSIONS OMBUDSMAN". OPSI. Retrieved 26 February 2010.

- Paul Strachan (21 October 2004), BUSM Pension Plan, ref 25995/PS

- Pam Atherton (18 May 2005). "Another pensions problem for the Government". The Sunday Telegraph. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- "Work and Pensions-Written Questions:British United Shoe Machinery". Hansard. 5 April 2005. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- Pam Atherton (29 June 2005). "Hewitt calls for new inquiry into BUSM pensions". The Sunday Telegraph. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- Patricia Hewitt MP (21 June 2005), Letter to Alan Johnson MP Ref CARL002/050826

- Alan Johnson MP (25 July 2005), letter from Alan Johnson MP to Patricia Hewitt MP

- "Stakeholder Pensions". Hansard. 25 July 2005. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- Pam Atherton (25 July 2005). "Government agrees to BUSM pension inquiry". The Sunday Telegraph. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- Daniel McAllister (6 February 2006). "Apax faces inquiry into BUSM scheme conduct". Pensions Week.

- DWP Letter to Edward Garnier MOS(PR)/05/1595

- Andy Reed MP (5 May 2007). "BUSM Pension Collapse in Leicestershire". Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- "Application 20070419 Ross Walk BUSM site". Leicester City Council. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- "Leicester Chimney Demolition BBC 1 East Midlands 21.01.12 1727.wmv". Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- "About Us". BUhistory.org.uk. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- Alan Thompson (23 November 2012). "Lotto funding boost helps people to explore history". Leicester Mercury. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

External links

- BU History group ..a Lottery funded website describing the experiences of workers at the B.U. and inviting contributions.

- BBC People's War British United Shoe Machinery Company (in WW2), author Kenneth Pearce Company 3473337 USM Group Holdings Reports and Accounts 31 December-1998

- https://web.archive.org/web/20141227215923/http://www.sdsa.net/images/WW1-SPSF/Resource%20Pack%203%20Research%20Guides%20-%20Factories.pdf

- Clippings about British United Shoe Machinery in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW