British Entomology

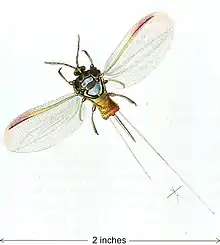

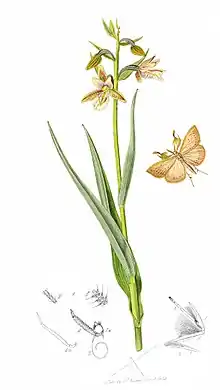

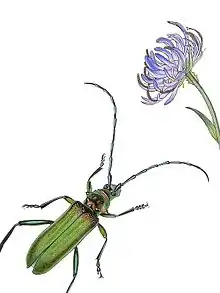

British Entomology is a classic work of entomology by John Curtis, FLS. It is subtitled Being Illustrations and Descriptions of the Genera of Insects found in Great Britain and Ireland: Containing Coloured Figures from Nature of the Most Rare and Beautiful Species, and in Many Instances of the Plants Upon Which they are Found.

The work comprises 770 hand-coloured, copper-plate engravings, each 8 by 5 1⁄2 inches (20×14 cm), together with two or more pages of text. The work was issued in monthly parts over 16 years, each part comprising three or more (usually four) plates. Plates were initially printed on James Whatman's Turkey Mill paper and then (circa 1832) on Rye Mill paper.

It was a masterpiece of the engraver's and colourist's art, described by the eminent French naturalist Georges Cuvier as the "paragon of perfection". Close examination of a proof set of plates (see below) reveals an obsessive attention to detail. The shading of the foliage is typically achieved by multiple, finely engraved lines spaced at intervals of five or more to the millimetre. The fronds (olfactory receptors) of many moth antennae are individually coloured – as in plate 674 (left). Several beetles and flies have body and limb highlights picked out in minute dots and lines of powdered gold. Thoracic and abdominal hairs are mostly painted individually. Where transparent wings are shown extended the colouring involved the precise application of multiple colour washes overlaid by a satin finish, gum arabic glaze to reproduce the visual effect of iridescence.

Almost every plate includes an equally well rendered botanical element, often the dominant part of the illustration. In a footnote to the first plate, Curtis explains this as follows:

Whenever the plant to which an insect is attached can be obtained, it will be introduced in the plate; but as some feed upon putrid animal and vegetable substances, many upon each other, and as not infrequently their habits are totally unknown, - in such instances plants will be introduced with a view to make the work as handsome and instructive as possible; and as a knowledge of Botany is absolutely necessary in order to be able to collect insects with complete success, it is hoped that figures of the indigenous plants will prove acceptable and useful to the reader.

Every illustration and line drawing was engraved or finished by Curtis himself, all the plates in volumes I, II, XV and XVI were engraved entirely by his hand. He also personally coloured the four proof sets and very closely supervised the hand colouring of all other plates. The final issue of the first edition (December 1839) included comprehensive indexes to all volumes plus a newly written eight-page preface summarising the production, costs and efforts involved. Also published at that time was a complete list of subscribers for each volume and detailed instructions for binding the work into eight volumes to generate the correct sequence of orders. Many copies were, however, bound in the alternative manner as sixteen volumes with the plates in numerical order. Curtis's original 778 drawings (some drawings were combined to produce a single plate, e.g. plate 703) were purchased by Lord Rothschild whose heirs, after having unsuccessfully tried to sell them in 1910, donated them to the Natural History Museum, London.

The work was unsystematically produced but each plate is dated, so this generally introduces no problems of name priority. However, confusion can arise with reprinted plates 1 to 34 (see below) where the text was rewritten, often with changes to nomenclature, yet the dates shown on the plates remained unchanged.

Aside from its noted illustrations, British Entomology is a work of taxonomy introducing many new species. This is especially true of the folios on Diptera and Hymenoptera. In his preface to the work, published in December 1839, Curtis writes: "... the articles and descriptions are my own writing; for any errors therefore I alone am accountable". However, it is clear from the dedications to the individual volumes that he had help from the likes of Alexander Henry Haliday, James Charles Dale, William Kirby and others.

If systematically bound as intended and instructed by Curtis, the resulting eight-volume set will be as follows:

- Volume 1 – Coleoptera (Part 1) dedicated to William Kirby and Alexander Macleay

- Volume 2 – Coleoptera (Part2) dedicated to William Jackson Hooker and John Stevens Henslow

- Volume 3 – Dermaptera, Dictyoptera, Orthoptera, Strepsiptera, Hymenoptera (Part 1) dedicated to John Lindley and Charles Lyell

- Volume 4 – Hymenoptera (Part 2) dedicated to Pierre André Latreille and William Sharp Macleay

- Volume 5 – Lepidoptera (Part 1) dedicated to James Charles Dale and Charles Daubeny

- Volume 6 – Lepidoptera (Part 2) dedicated to Charles A. Harris and William Spence

- Volume 7 – Homoptera, Hemiptera, Aphaniptera dedicated to Alexander Henry Haliday, Henry Walker and Francis Walker

- Volume 8 – Diptera, Omaloptera, dedicated to Henry Brown, Henry Nesbitt and the Earl of Malmesbury

Due to its relative slimness, Curtis recommended that the indexes be placed at the end of Volume VII. However, most systematic bindings have the general indexes more conventionally placed at the end of Volume VIII.

Publication history

- First edition

Announcement in the Somerset House Gazette, Volume I, January 1824:

On the 1st of January, 1824, will be Published (to be continued Monthly,) Price 3s 6d. plain, 4s.6d. coloured, No.I. of British Entomology; or Illustrations and Descriptions of the Genera of Insects found in Great Britain and Ireland; containing Coloured Figures of the most rare and beautiful species, and of the Plants upon which they are found, &c. By John Curtis, F.L.S.

The initial subscribers' list comprised 167 names, of whom 87 were committing to take the entire work even though the total size and final publication date were then unknown. Publication commenced as announced with a proposed print run of 200 copies of each part to be issued monthly over 16 years as annual volumes each of 12 parts – 192 parts in all. Each monthly part to comprise three or more, usually four, plates with accompanying text. By January 1839 the list of subscribers had fallen to 142. Of the original subscribers, only 31 eventually purchased all 192 first-edition parts on the day of issue and of these, three were joint-subscribers for a single set and two others each purchased two sets. Curtis's set is known to have included the later reprints of parts 1 to 8. The final subscribers' list of January 1840 shows that two complete sets were sold in December 1839 to previously unrecorded subscribers, "G. Folliott Esq., Chester (proofs)" and "Mrs Butler, Vicar's Cross". Curiously, at the time the only occupied dwelling at Vicar's Cross was the mansion owned and occupied by George Folliott and his immediate family and servants, none of whom was named Butler. The Butler set almost certainly included all the reprints.

A complete, sixteen-volume, chronologically bound set was sold from Curtis's estate on 8 June 1863 (John C. Stevens, auctioneer, King Street, Covent Garden, London – Lot 54) but it is not known whether or not this exclusively comprised first-edition parts – it could be the harlequin set now with the British Entomological Society. The same sale also included an incomplete set of five volumes (Lot 55), a quantity of faulty prints (Lot 93) and a large quantity of good, loose coloured plates (Lot 95).

At most, including proofs, just 32 complete first-edition sets, free of reprints, are definitely known to have been issued.

- Proof impressions

In spite of the finely detailed illustrations being more suited to steel-plate engraving, copper was used throughout. Curtis gives no clue as to why he made this choice. Copper plates noticeably degrade after as few as 50 impressions and so the earlier impressions, especially the proof sets, are of significantly higher quality and more finely detailed than those that followed.

Four complete sets of proof impressions, personally coloured by Curtis, were produced. These were sold at a considerable premium; one to Michael Bland of Paddington, London, and one to George Folliott of Vicar's Cross, Cheshire. The remaining two being taken by James Wadmore of Chapel Street, London.

A proof set can most easily be identified by reference to plate 717 (sycamore scale-insect - Coccus aceris), the first plate in Volume VII of a systematically bound set. The two setae of this insect are each delineated by two clearly separated, very fine lines; the left most of which is so fine as to be barely visible. Curtis significantly emboldened these lines for the standard impressions.

- Reprint of Parts 1 to 8 (plates 1–34) and Parts 9 to 30

Demand from later, new subscribers required Curtis retrospectively to print at least an additional 72 sets of parts 1 to 30. This reprinting commenced in January 1829 and continued until 1840 and was concurrent with the printing of the remaining parts 31 to 192 of the first edition which were increased in number to accommodate the additional demand.

Reprints of the plates and text of parts 1 to 8 (plates 1 to 34) can be all identified by an underscore to the plate number and in the case of plate 30, also by the addition of the systematic reference number 283. The text was comprehensively rewritten and reset with changes to nomenclature that later caused taxonomists some confusion since the dates on the accompanying plates were left unchanged. Parts 9 to 30 were reset and reprinted without material alteration except for an underscore to some of the plate numbers. The reprinted plates and many of the plates from parts 31 to 192 show evidence of the finer details having been reworked and are noticeably coarsened as a result.

- Total production

In January 1840 Curtis stated in the heading of the final List of Subscribers that; "It is impossible to complete the sets belonging to the Parties ... having only taken a few of the early volumes" indicating that he had ceased production of plates and parts and sold out of essential back copies. This list shows a final total output of 216 completed sets including proofs and reprints. Curtis's personal copy brings the total to 217. The list also shows that 54 partial sets were issued. To these figures should be added an unknown quantity of individual parts and plates sold separately. Therefore, total production was in excess of 210,000 plates, most of which were coloured. A monumental undertaking requiring an output of 44 fully finished plates and associated text every working day for 16 years.

- Original costs and prices

As a footnote to the preface issued with the final part in December 1839, John Curtis wrote: "To enable those who are ignorant of the nature of such undertakings, to form some conception of their risk and magnitude, it may be here stated, that the colouring alone of the Plates has already cost upwards of £3000", equivalent to £350,000 today (2017, Bank of England Sterling Index). Those subscribing for all 192 coloured parts were committing to a total purchase price of £43.4s.0d., approximately the average annual income for a family living in London with husband, wife and one child working.

- Lovell Reeves Edition

In 1862, Lovell Reeves published a partial reprint of the text and plates, the full details of which are now unknown except that all the plates were hand-coloured, lithographic copies easily identifiable today by their inferior quality with the dissection line drawings enlarged and randomly relocated. Plates and text from this reprint can sometime be found making up what would otherwise be an incomplete original set (see below). This edition was promoted in North America where Curtis had made no attempt to sell the original work.

Contemporary reviews

From: The Entomological Magazine, Volume I, 1832. Page 29.

Mr. Curtis commenced his beautiful work on the first of January, 1824, and has, with the most rigid punctuality, continued it in monthly numbers from that time to the present. We cannot be expected minutely to criticise such a mass of matter as must be contained in so extensive and laboured a production, yet we trust a few general observations will not be unacceptable to our readers.

Each number contains four highly finished and accurately coloured figures of insects, with dissections of the parts from which the generic characters are taken, at the foot of the page.

Each of these figures is intended to illustrate a genus; and in order to be able to give plates of the most rare and beautiful species of each genus, and to record fresh discoveries as they occur, Mr. Curtis has not followed the usual plan of adopting any system of arrangement; a plan by which an author is frequently bound to publish sections of his subject, which have never obtained sufficient attention to bring them into anything approaching a state of perfection. There are, perhaps, disadvantages attending this plan while in progress; but ultimately the work must, by this mode of publication, be rendered much more complete than it possibly could have been, had the genera been figured in regular succession. The plates, generally, represent one Coleopterous, one Hymenopterous, one Lepidopterous, and one Dipterous or Hemipterous insect ; and we may safely say, we have never seen representations more elegant, or more true to nature. The dissections we have, in many instances, examined and compared with the originals; and we are enabled to bear our testimony to their accuracy; and are convinced that engravings of this kind, tend more to fix the characters of genera on the mind than the most laboured descriptions.

Mr. Curtis frequently, in his plates of Lepidoptera, gives a figure of the larva, together with the plant on which it feeds: and, unwilling as we are to find fault, we feel we shall not be doing our duty to the public without expressing our disapprobation of a practice which Mr. Curtis has latterly too frequently adopted; we mean, that of copying the larvae from the figures of Continental authors, instead of from real British specimens.

Mr. Curtis must be thoroughly aware, that the same species varies so much in different climates, as to size, colour, and form, that it would be quite incorrect to figure an exotic specimen as British, even of an insect decidedly ascertained to be a native: secondly, every one is aware of the great propensity in our Continental neighbours to exaggerate their drawings, both as to size and colour: and, thirdly, Hübner's acknowledged carelessness about names, must frequently be a cause of error; and this error thus becomes perpetuated. We feel confident Mr. Curtis's excellent sense will convince him of the validity of these objections, especially when we assure him that many of his subscribers would prefer having no figure of the larva at all, to one copied from a foreign author. The gaudy caterpillars already figured, give to this part of the work a semi-foreign appearance, which deteriorates its value in the eyes of the British Entomologist: we speak not unadvisedly; we make ourselves the organ of the sentiments of others

In future numbers of this magazine, we purpose examining minutely every number of Mr. Curtis's, and all other periodicals which may intervene between the appearance of our own numbers ; but it is obvious we cannot suitably infringe on our allotted space for that purpose now, as it is necessary to give a general idea of each work before commencing the more laborious detail. We conclude, by heartily recommending the work before us to the attention and patronage of every British Entomologist; and we already have the happiness of knowing that, on the Continent of Europe, it is held in the highest esteem.

The criticism outlined in the penultimate paragraph was entirely unjustified as Curtis was well aware of the danger and modified Jacob Hübner's slightly exaggerated and somewhat crudely rendered original drawings so as to portray the true characteristics of the British subspecies. At no time since has any entomologist supported the criticism or made comment as to the inaccuracy of the colouring or size of the larval depictions.

From: The Gentleman's Magazine, 1826. Page 153.

Nature seems to have exhausted her wonderful talent for variety among the insect tribes. In the forms and dispositions of their members the wonderful modes of their generation and peculiarity without end, they vary from other animal beings, and yet perform the same functions; in short, though we know not all they do, we know nevertheless that they are not inconsiderable agents in the economy of Providence. But it is useless to expiate on topics which elementary school books have exhausted.

The principal object of Mr. Curtis is to give Entomology the same advantages in this country which it has long enjoyed on the Continent; and no one who has seen the work can possibly deny the highest praise to the execution of it. Eight new genera have been established, and figures of seventeen of the species have never before been published in any work; nor have the character of eight others been given in any English book. The descriptions are truly Linnæan; and to add to the effect and utility of the plates, figures of the flowers usually haunted by the respective insects are added, as well as all the members in dissection. Mistakes are carefully noted and corrected. Of the necessity for this addition we have good instance, in the hydaticus cinereus. Fabricus had confounded it with the male of Dyticus Salcatus, referring to Lennæus for the characters, and to Schæffer’s figure of D. Salcatus to identify it.

This is to exhibit the portrait of one man, as intended for another, to teach A for B, and the consequence necessarily is, that a book containing such errors is worse than none at all; for a man had better not learn Latin at all, than for a dictionary, which makes hate the English of amo, and so forth.

Surviving copies

Report by C. Davies Sherborn and J. Hartley Durrant. 1 March 1911.

The book consisted of sixteen volumes of twelve parts each, = 192 parts. There were 770 plates (1-769 and 205* duplicated for Hipparchis arcanius) each (first edition) with two pages of text.

Parts one and two had five plates each (plates 1–10) : parts 3–59 four plates each (plates 11–238) : part 60 had four plates (plates 239–241 and an extra plate and text 205* for Hipparchia arcanius) ; parts 61–192 four plates each (plates 242–769): total 770 plates. The break in part 60 of three consecutively numbered plates, instead of four, throws out one's calculations, but the total number of plates is re-adjusted by the additional plate 205.*

One number a month was issued with great regularity, commencing January 1824, and finishing December 1839, so the dates on the plates may be accepted with certainty. In the Entomological Magazine, i, 1833, p. 303, it was announced that the British Entomology would appear in alternate months in double parts, and this arrangement seems to have begun with parts 109–110 and is noticed to continue to parts 117 and 118. We have also wrappers for 159 and 160, and 169 and 170, but one may conjecture this to have been an irregular proceeding, for the Linnæan Society of London received most of the parts separately from Curtis himself, as seen by the Donation Book of that Society, itself a most valuable record for many works.

We do not therefore think that there is any need to disturb the dates given on the plates, at this distance of time, for the sake of a few odd bi-monthly issues, which it would be most difficult now to date with accuracy.

In 1829 Curtis may have found his stock of back numbers running short, he began a second edition. Parts one to eight were re-written and enlarged, some from two to ten pages, with alterations of nomenclature and additions; parts nine to thirty were reset and reprinted without alteration or addition ; and parts 31 to 192 were all of the first edition, i.e., one setting and one printing.

The only complete copy of original first editions we have handled is that belonging to the Linnæan Society ; the Entomological Society's copy (Curtis' own) is "made up" by the replacement of second editions of the early parts as more up-to-date: so is the copy in the British Museum (Nat. Hist.) which was the Earl of Sheffield's, but having a fine copy of the first edition of volume one separately, the British Museum (Nat. Hist.) does now possess the entire first edition.

A very fine copy of the complete second edition in the original boards with all the replacing title pages, &c., which are dated "1823–1840" is also in the British Museum (Nat. Hist.) as is also Lovell Reeves’ reprint of the second edition issued in 1862 (to the best of our knowledge).

It is interesting to note that at this present moment (Jan., 1911) the 770 original drawings for this beautiful work are being offered for sale by a well-known London bookseller.

Note: The drawings were shortly thereafter withdrawn from sale and given to the British Museum.

As of January 2018, of the known, surviving bound sets, that held by the Natural History Museum, London (subscribed for by the Earl of Sheffield) originally comprised second edition versions of parts 1 - 30 but was corrected some time prior to 1911 by the separate acquisition of a first edition of Volume I. The set belonging to the Linnaen Society is all good except that it contains a number of uncoloured illustrations. The copy held by The British Library is reportedly made up from many sources and editions. Another at The Smithsonian is made up from three part sets, lacks 117 plates with 3 plates uncoloured but is in reasonable overall condition. An apparently complete set of first edition plates and text, systematically arranged and bound in contemporary half calf covers is held by Kings College, London. It is in generally good condition but suffers strong paper toning and appears mainly to comprise end-of-run impressions as they are all very coarse and lack much of the finest detail. Curtis's own set, now with the Royal Entomological Society, includes all the reprints. A reportedly complete set, chronologically bound in 16 volumes, is held by Melbourne Museum. It was acquired by the museum in July, 1857 (via MacMillan of London), but its condition and make-up have not yet been investigated. Another set is held by the National Library of Ireland, another is to be found in the London library of the Royal Horticultural Society and a third by the Ulster Museum once belonged to George Crawford Hyndman. Two copies are catalogued by University of California, Berkeley libraries; one of which is incomplete, mis-bound, with reprints and at least one duplication (plate 638). Their second copy has not been located.

Two allegedly complete first-edition sets were recently sold at auction in Hamburg, Germany. Firstly, in May 2015, a set in good condition within modest, slightly damaged half-leather bindings formerly owned by John Waterhouse of Halifax, astronomer (not a subscriber) and secondly, on 20 November 2017, a reasonable set but with worn half-leather covers, provenance not disclosed. The whereabouts of these two are currently unknown. It is possible that they are both the same set, having suffered somewhat in the intervening thirty months.

Two complete, systematically arranged first-edition proof sets are in a private library in West Sussex, England. The first is one of the two sets subscribed for by James Wadmore of Paddington. It bears later ownership stamps; "T.H.T. Hopkins Magd: Coll: Oxford" for Thomas Henry Toovey Hopkins (1831–1885) at the College of St. Mary Magdalen, Oxford, England. This set, bound in green half morocco and faux buckram bindings, is in excellent condition . The second, formerly at the Edge Hall Library, Malpas, Cheshire, England was originally purchased, as a complete set, directly from Curtis in December 1839, by George Folliott (1801-1851) of Vicar's Cross House, Chester. On Folliott's death in 1851 it passed to his close friends, the Dod family (specifically; Frances Rosamond Dod) at nearby Edge Hall and thence by descent to Mr. A.K. Wolley Dod whose Residuary Trust disposed of the more important works in the Edge Hall Library via auction in 2017 whence it was acquired by the present owner. It was not described in the catalogue as being a proof set. It is the finest known survivor with contemporary bindings by White of Pall Mall in green, full morocco leather with triple-edge page gilding and inner gilt dentelles. The remaining two proof sets, if they have survived, remain to be discovered.

All other known, surviving complete sets appear to include reprints and lithographed substitutes making up the shortfalls. Those listed as being in American universities usually comprise the 1862 lithographic reprints, either that or their catalogues are referring to one of the harlequin copies held either by the U.C. Berkeley or the Ernst Mayer Library or the on-line copies freely accessible via the Biodiversity Heritage Library. In March 1911, after a lengthy search, C. Davies Sherborn and J. Hartley Durrant of The Entomological Society of London could locate only one properly complete set free of reprints and lithographed replacements, namely that held by the Linnaen Society library (see above). In 1947 Richard E. Blackwelder investigated the five sets then known to be held in the United States, the results of his enquiries were published by The Smithsonian as the Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, Volume 107, Number 5, entitled "The Dates and Editions of Curtis' British Entomology". All five sets examined by Blackwelder were found to be made-up, including several lithographed copy plates.

As of 1 December 2019, eleven, complete, original, first edition copies, two with partially coloured plates, have been located and positively identified. Beyond these there are twenty other known examples, either incomplete or made up from later editions and reprints. The finest, most accurately illustrated and precisely coloured entomological (and botanical) publication ever produced is now also one of the rarest.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to British Entomology (John Curtis). |

- Detailed taxonomic descriptions of British insects, accompanied by quality scans of all the Curtis plates with updated names for all the insects and plants illustrated by him

- British Entomology at Google Books

- BHL Scans of 653 (of 770) plates and text. Medium quality. Downloads.

- YouTube Video with close-ups of 40 plates from the Wadmore-Hopkins set. High quality.