Bristol Castle

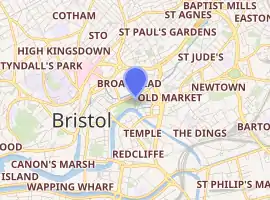

Bristol Castle was a Norman castle built for the defence of Bristol. Remains can be seen today in Castle Park near the Broadmead Shopping Centre, including the sally port.

| Bristol Castle | |

|---|---|

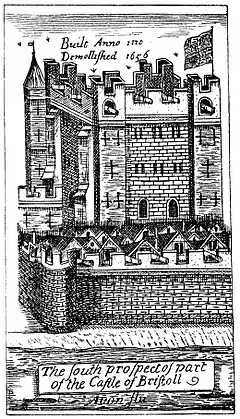

Bristol Castle viewed from the River Avon. Detail from James Millerd's map of Bristol, 1673 | |

| |

| General information | |

| Town or city | Bristol |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 51°27′21.4″N 2°35′17.51″W |

| Client | William the Conqueror |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Robert, 1st Earl of Gloucester |

Site

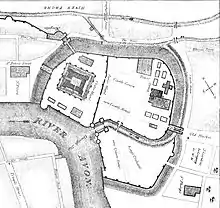

The castle was built on a strategic site on the eastern side of the walled town, between the River Avon on the south and the River Frome on the north, joined by a canal to form the castle moat on the east side, with weir on the north to compensate for differing water levels in the two rivers. As the town of Bristol was itself built in the angle of the junction of those two rivers, by the construction of the castle moat, the town and castle became completely surrounded by water and thus highly defensible.[1]

History

The first castle built at Bristol was a timber motte and bailey, presumably erected on the command of William the Conqueror, who retained the manor of Bristol within the royal demesne. One of William's closest allies, Geoffrey de Montbray, Bishop of Coutances, appears to have had control of the castle in William's name. The Domesday Book of 1086 records that he received part of the king's income from the borough. The castle is first mentioned in surviving records in 1088, when Geoffrey used it as a base in his rebellion against King William II.[2]

After William II triumphed, the English lands of the rebels were redistributed to his loyal followers. Among the recipients was Robert FitzHamon, who having thus gained a large swathe of Gloucestershire, including Bristol Castle, founded the feudal barony of Gloucester. His eldest daughter and heiress Mabel FitzHamon married Robert, 1st Earl of Gloucester, illegitimate son of King Henry I. On the death of her father in 1107, Mabel brought to her husband the feudal barony of Gloucester: thus he is generally known as "Robert of Gloucester".[3]

.jpg.webp)

This great fortress was to play a key role in the civil wars that followed the death of Henry I of England. Henry's only legitimate son William drowned in 1120, so Henry eventually declared his one legitimate daughter Matilda his heir. However her cousin, Stephen of Blois usurped the throne on Henry's death in 1135. Matilda's half-brother Robert of Gloucester became her trusted right-hand man – the commander of her troops. Rebels rallied to his castle at Bristol.[5]

Stephen reconnoitred Bristol in 1138 but decided that the town was impregnable. As his chronicler reported: "On one side of it, where it is considered more exposed to siege and more accessible, a castle rising on a vast mound, strengthened by wall and battlements, towers and divers engines, prevents an enemy's approach." [6] After Stephen was captured in 1141, he was imprisoned in Bristol Castle until Robert of Gloucester was also captured and an exchange of prisoners was made.[7]

The castle and title of Earl of Gloucester passed to Robert's son, William. When Henry the Young King and his brother – princes Richard and Geoffrey – rebelled against King Henry II in 1173 Earl William supported their cause. The rebellion was put down the following year, and William was punished by having Bristol Castle confiscated and taken under royal control. Bristol became one of the most important royal castles in the country. Henry III, educated there in his youth, spent lavishly on it, adding a barbican before the main west gate, a gate tower, and magnificent great hall. From 1224, Eleanor of Brittany was strictly confined to the castle under relatively comfortable conditions, with accommodation in the keep.[8]

The two young sons of Dafydd ap Gruffydd, the last princes of Gwynedd, were imprisoned for life in Bristol Castle after Edward I's conquest of Wales in 1283. William le Scrope, Sir John Bussy and Sir Henry Green were executed there without trial in June 1399 by the Duke of Hereford, soon to be King Henry IV of England, after the latter's successful return from exile.[9]

The first detailed description of the castle was written in 1480.[10] By the time the antiquary John Leland visited c.1540, Bristol castle was showing signs of neglect. It had "two courts, and in the north-west part of the outer court there is a large keep with a dungeon, said to have been built of stone brought by the red Earl of Gloucester from Caen in Normandy. In the other court is an attractive church and many domestic quarters, with a great gate on the south side, a stone bridge and three ramparts on the left bank leading to the mouth of the Frome. Many towers still stand in both the courts, but they are all on the point of collapse.".[11] By the sixteenth century the castle had fallen into disuse, but the City authorities had no control over royal property and the precincts became a refuge for lawbreakers. In 1630 the city bought the castle and when the Civil War broke out the city took the Parliamentary side and partly restored the castle. However Royalist troops occupied Bristol and after it was recaptured in 1645, Oliver Cromwell ordered the destruction of the castle.[12]

The castle was demolished in 1656, according to Millerd's map of Bristol (above right). However one octagonal tower survived until it was torn down in 1927. It was sketched by Samuel Loxton in 1907.[13] There are some remains of the banqueting hall incorporated in a building which still exists above ground today, known as the Castle Vaults. In 1938 the Castle Vaults was used as a tobacconists shop.[14]

The castle moat was covered over in 1847 but still exists and is mainly navigable by boat, flowing under Castle Park and into the Floating Harbour. The western section is a dry ditch and a sally port into the moat survives near St Peter's Church.[15]

A 16-metre (52 ft) long postern tunnel runs underneath the south west part of the castle.[16]

Today

The area was redeveloped for commerce, and later largely destroyed in the 'Bristol Blitz'. It was subsequently redeveloped as a public open space, Castle Park.[17]

The vaulted chambers of the Castle are a Scheduled Ancient Monument.[18]

Notes

- S. Watson, Secret underground Bristol (Bristol 1991) ISBN 0-907145-01-9

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

- G.E.C[okayne], The Complete Peerage, 2nd edn. ed. V. Gibbs (London 1910–59).

- "Bristol Past and Present" (Arrowsmith, 1881, pages 74-79), J. F. Nicholls and John Taylor

- Chibnall, Marjorie, The Empress Matilda (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991), p.83

- Gesta Stephani ed. and trans. K.R. Potter (Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1976), pp. 37–8, 43–4.

- William of Malmesbury, The Historia Novella, trans. K. R. Potter (London : T. Nelson, 1955), p.50.

- Colvin, H. M.; Brown, R. A. (1963), "The Royal Castles 1066–1485", The History of the King's Works. Volume II: The Middle Ages, London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, pp. 578–579

- "GREEN, Sir Henry (c.1347-1399), of Drayton, Northants". History of Parliament. The History of Parliament Trust. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- William Worcestre, The Topography of Medieval Bristol, Bristol Record Society vol. 51 (2000), nos. 396, 422.

- John Leland's Itinerary: Travels in Tudor England, ed. John Chandler (Sutton Publishing: Stroud, 1993), pp. 178–9.

- "History and Archaeology of Castle Park" (PDF). Bristol City Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- George Frederick Stone, Bristol As It Was And As It Is (Bristol 1909), p. 99.

- Andrew Foyle & David Martyn, Bristol: City on Show, The History Press, 2012

- "Bristol Castle". Fortified England. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- Wilson, David M; Moorhouse, Stephen (1971). "Medieval Britain in 1970" (PDF). Medieval Archaeology. 15: 146. doi:10.5284/1000320.

- Hasegawa, Junichi (1992). "6 Replanning the city centre: Bristol 1940-45". Replanning the blitzed city centre. Open University Press. ISBN 0-335-15633-9.

- "Scheduled Ancient Monuments in Bristol". Bristol City Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 7 May 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bristol Castle. |

- Bristol Castle : a history by Jean Manco from Bristol Past.

- English Heritage Monument No. 1009209

- Investigation History