Breast augmentation

Breast augmentation and augmentation mammoplasty (colloquially: "boob job") is a cosmetic surgery technique using breast-implants and fat-graft mammoplasty techniques to increase the size, change the shape, and alter the texture of the breasts of a woman. Augmentation mammoplasty is applied to correct congenital defects of the breasts and the chest wall. As an elective cosmetic surgery, primary augmentation changes the aesthetics – of size, shape, and texture – of healthy breasts.

| Breast augmentation | |

|---|---|

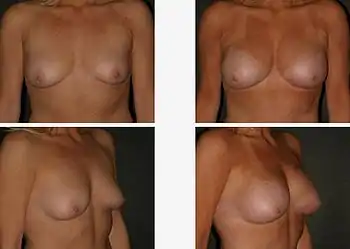

The pre-operative aspects (left), and the post-operative aspects (right) of a bilateral, sub-muscular emplacement of 350 cc saline implants through an infra-mammary fold (IMF) incision | |

| Specialty | plastic surgeon |

The surgical implantation approach creates a spherical augmentation of the breast hemisphere, using a breast implant filled with either saline solution or silicone gel; the fat-graft transfer approach augments the size and corrects contour defects of the breast hemisphere with grafts of the adipocyte fat tissue, drawn from the person's body.

In a breast reconstruction procedure, a tissue expander (a temporary breast implant device) is sometimes put in place and inflated with saline to prepare (shape and enlarge) the recipient site (implant pocket) to receive and accommodate the breast implant prosthesis.

In most instances of fat-graft breast augmentation, the increase is of modest volume, usually only one bra cup size or less, which is thought to be the physiological limit allowed by the metabolism of the human body.[1]

Surgical breast augmentation

Breast implants

There are four types of implant:

- Saline implants filled with sterile saline solution

- Silicone implants filled with viscous silicone gel

- Alternative-composition implants (no longer manufactured), filled with various fillers such as soy oil or polypropylene string

- "Structured" implants using nested elastomer silicone shells with saline between the shells.[2]

Saline breast implant

The saline breast implant, filled with saline solution, was first manufactured by the Laboratoires Arion company, in France, and introduced for use as a prosthetic medical device in 1964. Modern-day versions of saline breast implants are manufactured with thicker, room-temperature vulcanized (RTV) shells made of a silicone elastomer. The study In vitro Deflation of Pre-filled Saline Breast Implants (2006) reported that the rates of deflation (filler leakage) of the pre-filled saline breast implant made it a second-choice prosthesis for "corrective breast surgery".[3] Nonetheless, in the 1990s, the saline breast implant was mandated to be the prosthesis usual for breast augmentation surgery, the result of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) temporary restriction against the importation of silicone-filled breast implants.

The technical goal of saline-implant technique was a less-invasive surgical technique, by inserting an empty, rolled-up breast implant through a smaller surgical incision.[4] In surgical practice, after having installed the empty breast implants in the implant pockets, the plastic surgeon would then fill each device with saline solution through a one-way valve and, because the required insertion incisions were short and small, the resultant incision scars would be smaller and shorter than the surgical scars typical of the pre-filled, silicone-gel implant surgical technique.

When compared with the results achieved with a silicone-gel breast implant, the saline implant can yield "good-to-excellent" results of increased breast size, a smoother hemisphere-contour, and realistic consistency; yet it is likelier to cause cosmetic problems, such as the rippling and the wrinkling of the breast-envelope skin, and technical problems, such as the implant's presence being noticeable to the eye and to the touch. The occurrence of such cosmetic problems is likelier in the case of a person with very little breast tissue; in the case of a person who requires post-mastectomy breast reconstruction, the silicone-gel implant is the technically superior prosthetic device for breast reconstruction. In the case of the person with much breast tissue, for whom sub-muscular placement is the recommended surgical approach, saline breast implants can give an aesthetic result much like that produced by silicone breast implants – : an appearance of proportionate breast size, smooth contour, and realistic consistency.[5]

Silicone-gel breast implant

The modern prosthetic breast was invented in 1961, by the American plastic surgeons Thomas Cronin and Frank Gerow, and manufactured by the Dow Corning Corporation; in due course, the first augmentation mammoplasty was performed in 1962. There are five generations of medical device technology for the breast-implant models filled with silicone gel; each generation of breast prosthesis is defined by common model-manufacturing techniques.

First generation

The Cronin–Gerow implant, prosthesis model 1963, was a silicone rubber envelope-sack, shaped like a teardrop, which was filled with viscous silicone-gel. To reduce the rotation of the emplaced breast-implant upon the chest wall, the model 1963 prosthesis was affixed to the implant pocket with a fastener-patch, made of Dacron material (polyethylene terephthalate), which was attached to the rear of the breast implant shell.[6]

Second generation

In the 1970s, manufacturers offered the second generation of breast implant prostheses

- The first developments were a thinner-gauge implant shell, and a filler gel of low-cohesion silicone, which made the devices more functional and realistic (size, appearance, and consistency). Yet, in clinical practice, second-generation breast implants proved fragile, with greater rates of shell rupture and filler leakage ("silicone-gel bleed") through the "intact device's shell. The consequences, plus increased rates of capsular contracture, precipitated faulty product class action-lawsuits by the U.S. government against the Dow Corning Corporation and other manufacturers of breast prostheses.

- The second technological development was a polyurethane foam coating for the shell of the implant; the coating reduced the degree of capsular contracture by causing an inflammatory reaction that impeded the formation of a capsule of fibrous collagen tissue around the coated device. Nevertheless, despite the intentions behind the polyurethane foam coating, the medical use of polyurethane-coated breast implants was briefly discontinued due to the potential health risk posed by 2,4-toluenediamine (TDA), a carcinogenic by-product of the chemical breakdown of the polyurethane foam coating of the breast implant.[7]

- After reviewing the medical data, the FDA concluded that TDA-induced breast cancer was an infinitesimal health risk to anyone with breast implants, and did not justify legally requiring physicians to explain the matter to their patients. Ultimately, polyurethane-coated breast implants remain in plastic surgery practice in Europe and in South America; no manufacturer has sought FDA approval for medical sales of such breast implants in the U.S.[8]

- The third technological development was the double-lumen breast implant, a double-cavity prosthesis composed of a silicone breast implant contained within a saline breast implant. The two-fold, technical goal was: (i) the cosmetic benefits of silicone gel (the inner lumen) enclosed in saline solution (the outer lumen); (ii) a breast implantwhose volume is post-operatively adjustable. unfortunately, the more complex design of the double-lumen breast implant suffered a device-failure rate greater than that of single-lumen breast implants. This style of implant, in modern times, is primarily used for breast reconstruction.

Third and fourth generations

In the 1980s, the third- and fourth-generation implants were stepwise advances in manufacturing technology, such as elastomer-coated shells that decreased gel bleed (filler leakage), and a thicker, increased-cohesion filler gel. The manufacturers of implantable breast prostheses then designed and made anatomic models (like the natural breast) and "shaped" models, which realistically corresponded with the breast and body types of actual women. The tapered models of breast implant have a uniformly textured surface, to reduce rotation of the prosthesis within the implant pocket; round models of breast implant are available in both smooth-surface and textured-surface models, as rotation is not an issue.

Fifth generation

Since the mid-1990s, the fifth generation of silicone gel breast implant is made of a semi-solid gel, which mostly eliminates the occurrences of filler leakage ("silicone-gel bleed") and of the migration of the silicone filler from the implant-pocket to other areas of the person's body. The studies Experience with Anatomical Soft Cohesive Silicone gel Prosthesis in Cosmetic and Reconstructive Breast Implant Surgery (2004) and Cohesive Silicone gel Breast Implants in Aesthetic and Reconstructive Breast Surgery (2005) reported relatively lower rates of capsular contracture and of device-shell rupture, and relatively greater rates of "medical safety" and "technical efficacy" than those of early-generation breast implants.[9][10][11]

Alternative-composition implants

Saline and silicone gel are the most common types of breast implant used in the world today.[12] Alternative-composition implants have largely been discontinued. These implants featured fillers such as soy oil and polypropylene string. Other discontinued materials include ox cartilage, Terylene "wool", ground rubber, silastic rubber, and Teflon-silicone prostheses.[12]

"Structured" implants

Structured implants were approved by the FDA and Health Canada in 2014 as a fourth category of breast implant.[2] These implants incorporate both saline and silicone gel implant technology. The filler is saline solution, in case of rupture, and has a natural feel, like silicone gel implants.[13] This implant type uses an internal structure consisting of three nested silicone rubber "shells" that support the upper half of the breast, with the two spaces between the three shells filled with saline. The implant is inserted, empty, then filled once in place, which requires a smaller incision than a pre-filled implant.[2]

Implants and breastfeeding

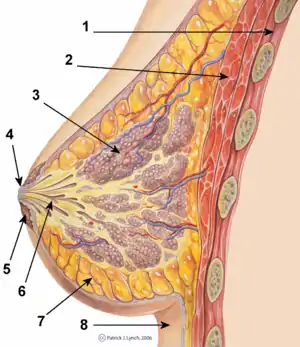

The breasts are apocrine glands which produce milk for the feeding of infant children,[14]

Breast implant toxicity

Digestive tract contamination and systemic toxicity due to the leakage of breast implant filler to the breast milk are the principal infant-health concerns with breast implants. Breast implant fillers are biologically inert: silicone filler is indigestible and saline filler is mostly salt and water. Each of these substances should be chemically inert and present in the environment. Moreover, "proponent" physicians have stated that there "should be no absolute contraindication to breast-feeding by women with silicone breast implants."[15] In the early 1990s, at the beginning of the silicone gel breast implant illness panic, small-scale, non-randomized studies indicated possible breast-feeding complications from silicone implants; no one study was able to demonstrate disease causality due to implants.[16]

Impediments to breastfeeding

A person with breast implants is usually able to breastfeed an infant; yet implants can cause functional breastfeeding difficulties, especially with mammoplasty procedures that involve cutting around the areola, and implant placement directly beneath the breast, which tend to cause greater breast-feeding difficulties. Patients are advised to select a procedure which causes the least damage to the lactiferous ducts and the nerves of the nipple-areola complex (NAC).[17][18][19]

Functional breastfeeding difficulties arise if the surgeon cuts the milk ducts or the major nerves innervating the breast, or if the milk glands are otherwise damaged. Some surgical approaches, including IMF (inframammary fold), TABA (trans-axillary breast augmentation), and TUBA (trans-umbilical breast augmentation), avoid the tissue of the nipple-areola complex; if the person is concerned about possible breast-feeding difficulties, the periareolar incisions can sometimes be made so as to reduce damage to the milk ducts and to the nerves of the NAC. The milk glands are affected most by subglandular implants (under the gland), and by large-sized breast implants, which pinch the lactiferous ducts and impede milk flow. Small-sized breast implants, and submuscular implantation, cause fewer breast function problems; however, some women have managed to successfully breastfeed after undergoing periareolar incisions and subglandular emplacement.[19]

The patient

Psychology

The usual breast augmentation patient is a young woman whose personality profile indicates psychological distress about her personal appearance and her body (self image), and a history of having endured criticism about the aesthetics of her person.[20] The studies Body Image Concerns of Breast Augmentation Patients (2003) and Body Dysmorphic Disorder and Cosmetic Surgery (2006) reported that the woman who underwent breast augmentation surgery also had undergone psychotherapy, suffered low self-esteem, presented frequent occurrences of psychological depression, had attempted suicide, and suffered body dysmorphia – a type of mental illness wherein she perceives non-existent physical defects. Post-operative patient surveys about the mental health and the quality of life of the women, reported improved physical health, physical appearance, social life, self-confidence, self-esteem, and satisfactory sexual functioning. Furthermore, most of the women reported long-term satisfaction with their breast implants; some despite having suffered medical complications that required surgical revision, either corrective or aesthetic. Likewise, in Denmark, 8.0 percent of breast augmentation patients had a pre-operative history of psychiatric hospitalization.[21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29]

Women bodybuilders

The Cosmeticsurgery.com article They Need Bosoms, too – Women Weight Lifters (2013) reported that women weight-lifters have resorted to breast augmentation surgery to maintain a feminine physique, and so compensate for the loss of breast mass consequent to the increased lean-body mass and decreased body-fat consequent to lifting weights.[30]

Mental health

The longitudinal study Excess Mortality from Suicide and other External Causes of Death Among Women with Cosmetic Breast Implants (2007), reported that women who sought breast implants are almost 3.0 times as likely to commit suicide as are women who have not sought breast implants. Compared to the standard suicide-rate for women of the general populace, the suicide-rate for women with augmented breasts remained alike until 10-years post-implantation, yet it increased to 4.5 times greater at the 11-year mark, and so remained until the 19-year mark, when it increased to 6.0 times greater at 20-years post-implantation. Moreover, additional to the suicide risk, women with breast implants also faced a trebled death risk from alcoholism and drugs abuse (prescription and recreational).[31][32] Although seven studies have statistically connected a woman's undergoing a breast augmentation procedure to a greater suicide rate, the research indicates that augmenation surgery does not increase the suicide rate; and that, in the first instance, it is the psychopathologically inclined woman who is likelier to undergo breast augmentation.[33][34][35][36][37][38]

Moreover, the study Effect of Breast Augmentation Mammoplasty on Self-Esteem and Sexuality: A Quantitative Analysis (2007), reported that the women attributed their improved self-esteem, self-image, and increased, satisfactory sexual functioning to having undergone breast augmentation; the cohort, aged 21–57 years, averaged post-operative self-esteem increases ranging from 20.7 to 24.9 points on the 30-point Rosenberg self-esteem scale, which data supported the 78.6 percent increase in the woman's libido, relative to her pre-operative level of libido. Therefore, before agreeing to any surgical procedure, the plastic surgeon evaluates and considers the woman's mental health to determine if breast implants can positively affect her self-esteem and sexual functioning.[39]

Surgical procedures

Indications

An augmentation mammoplasty for emplacing breast implants has three therapeutic purposes:

- Primary reconstruction: to replace breast tissues damaged by trauma (blunt, penetrating, blast), disease (breast cancer), and failed anatomic development (tuberous breast deformity).

- Revision and reconstruction: to revise (correct) the outcome of a previous breast reconstruction surgery.

- Primary augmentation: to aesthetically augment the size, form, and feel of the breasts.

The operating room time of post–mastectomy breast reconstruction, and of breast augmentation surgery is determined by the emplacement procedure employed, the type of incisional technique, the breast implant (type and materials), and the pectoral locale of the implant pocket.[40]

Incision types

The emplacement of a breast implant device is performed with five types of surgical incisions:[41]

- Inframammary: an incision made below the breast, in the inframammary fold (IMF), which affords maximal access for precise dissection and emplacement of the breast implant devices. It is the preferred surgical technique for emplacing silicone-gel implants, because of the longer incisions required; yet, IMF implantation can produce thicker, slightly more visible surgical scars.

- Periareolar: an incision made along the areolar periphery (border), which provides an optimal approach when adjustments to the IMF position are required, or when a mastopexy (breast lift) is included to the primary mammoplasty procedure. In the periareolar emplacement method, the incision is around the medial-half (inferior half) of the areola's circumference. Silicone-gel implants can be difficult to emplace with this incision, because of the short, five-centimetre length (~ 5.0 cm.) of the required access-incision. Aesthetically, because the scars are at the areola's border, they usually are less visible than the IMF-incision scars of women with light-pigment areolae. Furthermore, periareolar implantation produces a greater incidence of capsular contracture, severs the milk ducts and the nerves to the nipple, thus causes the most post-operative functional problems, e.g. impeded breastfeeding.

- Transaxillary: an incision made to the axilla (armpit), from which the dissection tunnels medially, thus allows emplacing the implants without producing visible scars upon the breast proper; yet is likelier to produce inferior asymmetry of the implant-device position. Therefore, surgical revision of transaxillary emplaced breast implants usually requires either an IMF incision or a periareolar incision. Transaxillary emplacement can be performed bluntly or with an endoscope (illuminated video microcamera).

- Transumbilical: a trans-umbilical breast augmentation (TUBA) is a less common implant-device insertion technique wherein the incision is at the navel, and the dissection tunnels superiorly. This surgical approach enables emplacing the breast implants without producing visible scars upon the breast; but it makes appropriate dissection and device-emplacement more technically difficult. A TUBA procedure is performed bluntly – without the endoscope's visual assistance – and is not appropriate for emplacing (pre-filled) silicone-gel implants, because of the great potential for damaging the elastomer silicone shell of the breast-implant device during its manual insertion through the short – two-centimetre (~2.0 cm.) – incision at the navel, and because pre-filled silicone-gel implants are incompressible, and cannot be inserted through so small an incision.[42]

- Transabdominal – as in the TUBA procedure, in the transabdominoplasty breast augmentation (TABA), the breast implants are tunneled superiorly from the abdominal incision into bluntly dissected implant pockets, while the patient simultaneously undergoes an abdominoplasty.[43]

Implant pocket placement

The four surgical approaches to emplacing a breast implant to the implant pocket are described in anatomical relation to the pectoralis major muscle.

- Subglandular – The breast implant is emplaced to the retromammary space, between the breast tissue (the mammary gland) and the pectoralis major muscle (major muscle of the chest), which most approximates the plane of normal breast tissue, and affords the most aesthetic results. Yet, in women with thin pectoral soft-tissue, the subglandular position is likelier to show the ripples and wrinkles of the underlying implant. Moreover, the capsular contracture incidence rate is slightly greater with subglandular implantation.

- Subfascial – The breast implant is emplaced beneath the fascia of the pectoralis major muscle; the subfascial position is a variant of the subglandular position for the breast implant.[44] The technical advantages of the subfascial implant-pocket technique are debated; proponent surgeons report that the layer of fascial tissue provides greater implant coverage and better sustains its position.[45]

- Subpectoral (dual plane) – The breast implant is inserted beneath the pectoralis major muscle, after the surgeon releases the inferior muscular attachments, with or without partial dissection of the subglandular plane. Resultantly, the upper half of the implant is partially beneath the pectoralis major muscle, while the lower half of the implant is in the subglandular plane. This implantation technique achieves maximal coverage of the upper half of the implant, while allowing the expansion of the implant's lower half; however, “animation deformity”, the movement of the implants in the subpectoral plane can be excessive for some patients.[46]

- Submuscular – The breast implant is emplaced beneath the pectoralis major muscle, without releasing the inferior origin of the muscle proper. Total muscular coverage of the implant can be achieved by releasing the lateral muscles of the chest wall – either the serratus muscle or the pectoralis minor muscle, or both – and suturing it, or them, to the pectoralis major muscle. In breast reconstruction surgery, the submuscular implantation approach effects maximal coverage of the breast implants.

Post-surgical recovery

The surgical scars of a breast augmentation mammoplasty heal at 6-weeks post-operative, and fade within several months, according to the skin type of the woman. Depending upon the daily physical activity the woman might require, the augmentation mammoplasty patient usually resumes her normal life activities at about 1-week post-operative. The woman who underwent submuscular implantation (beneath the pectoralis major muscles) usually has a longer post–operative convalescence, and experiences more pain, because of the healing of the deep-tissue cuts into the chest muscles for the breast augmentation. The patient usually does not exercise or engage in strenuous physical activities for about six weeks. Moreover, during the initial convalescence, the patient is encouraged to regularly exercise (flex and move) her arms to alleviate pain and discomfort; and, as required, analgesic medication catheters for alleviating pain.[47][48]

Medical complications

The plastic surgical emplacement of breast-implant devices, either for breast reconstruction or for aesthetic purpose, presents the same health risks common to surgery, such as adverse reaction to anesthesia, hematoma (post-operative bleeding), seroma (fluid accumulation), incision-site breakdown (wound infection). Complications specific to breast augmentation include breast pain, altered sensation, impeded breast-feeding function, visible wrinkling, asymmetry, thinning of the breast tissue, and symmastia, the “bread loafing” of the bust that interrupts the natural plane between the breasts. Specific treatments for the complications of indwelling breast implants – capsular contracture and capsular rupture – are periodic MRI monitoring and physical examinations. Furthermore, complications and re-operations related to the implantation surgery, and to tissue expanders (implant placeholders during surgery) can cause unfavorable scarring in approximately 6–7% of the patients. [28][49][50] Statistically, 20% of women who underwent cosmetic implantation, and 50% of women who underwent breast reconstruction implantation, required their explantation at the 10-year mark.[51] The history of implants are not that long, therefore the more data accumulates, the better, to understand the risks. In 2019 after many years, in the US a direct link was identified between Allergan BIOCELL textured breast implants of Allergan and the breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL), a cancer of the immune system. FDA recalled all Allergan BIOCELL implants.[52]

Implant rupture

Because a breast implant is a Class III medical device of limited product-life, the principal rupture-rate factors are its age and design; Nonetheless, a breast implant device can retain its mechanical integrity for decades in a woman's body.[53] When a saline breast implant ruptures, leaks, and empties, it quickly deflates, and thus can be readily explanted (surgically removed). The follow-up report, Natrelle Saline-filled Breast Implants: a Prospective 10-year Study (2009) indicated rupture-deflation rates of 3–5 percent at 3-years post-implantation, and 7–10 percent rupture-deflation rates at 10-years post-implantation.[54]

When a silicone breast implant ruptures it usually does not deflate, yet the filler gel does leak from it, which can migrate to the implant pocket; therefore, an intracapsular rupture (in-capsule leak) can become an extracapsular rupture (out-of-capsule leak), and each occurrence is resolved by explantation. Although the leaked silicone filler-gel can migrate from the chest tissues to elsewhere in the woman's body, most clinical complications are limited to the breast and armpit areas, usually manifested as granulomas (inflammatory nodules) and axillary lymphadenopathy (enlarged lymph glands in the armpit area).[55][56][57]

- The suspected mechanisms of breast implant rupture:

- Damage during implantation

- Damage during (other) surgical procedures

- Chemical degradation of the breast implant shell

- Trauma (blunt trauma, penetrating trauma or blast trauma)

- Mechanical pressure of traditional mammographic breast examination [58]

Silicone implant rupture can be evaluated using magnetic resonance imaging; from the long-term MRI data for single-lumen breast implants, the European literature about second generation silicone-gel breast implants (1970s design), reported silent device-rupture rates of 8–15 percent at 10-years post-implantation (15–30% of the patients).[59][60][61][62]

The study Safety and Effectiveness of Mentor's MemoryGel Implants at 6 Years (2009), which was a branch study of the U.S. FDA's core clinical trials for primary breast augmentation surgery patients, reported low device-rupture rates of 1.1 percent at 6-years post-implantation.[63] The first series of MRI evaluations of the silicone breast implants with thick filler-gel reported a device-rupture rate of 1.0 percent, or less, at the median 6-year device-age.[64] Statistically, the manual examination (palpation) of the woman is inadequate for accurately evaluating if a breast implant has ruptured. The study, The Diagnosis of Silicone Breast-implant Rupture: Clinical Findings Compared with Findings at Magnetic Resonance Imaging (2005), reported that, in asymptomatic patients, only 30 percent of the ruptured breast implants is accurately palpated and detected by an experienced plastic surgeon, whereas MRI examinations accurately detected 86 percent of breast-implant ruptures.[65] Therefore, the U.S. FDA recommended scheduled MRI examinations, as silent-rupture screenings, beginning at the 3-year-mark post-implantation, and then every two years, thereafter.[28] Nonetheless, beyond the U.S., the medical establishments of other nations have not endorsed routine MRI screening, and, in its stead, proposed that such a radiologic examination be reserved for two purposes: (i) for the woman with a suspected breast-implant rupture; and (ii) for the confirmation of mammographic and ultrasonic studies that indicate the presence of a ruptured breast implant.[66]

Furthermore, The Effect of Study design Biases on the Diagnostic Accuracy of Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Detecting Silicone Breast Implant Ruptures: a Meta-analysis (2011) reported that the breast-screening MRIs of asymptomatic women might overestimate the incidence of breast-implant rupture.[67] In the event, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration emphasised that “breast implants are not lifetime devices. The longer a woman has silicone gel-filled breast implants, the more likely she is to experience complications.”[68]

When one lumen of a structured implant ruptures, it leaks and empties. The other lumen remain intact and the implant only partially deflates, allowing for ease of explant and replacement.[2]

Capsular contracture

The human body's immune response to a surgically installed foreign object – breast implant, cardiac pacemaker, orthopedic prosthesis – is to encapsulate it with scar tissue capsules of tightly woven collagen fibers, in order to maintain the integrity of the body by isolating the foreign object, and so tolerate its presence. Capsular contracture – which should be distinguished from normal capsular tissue – occurs when the collagen-fiber capsule thickens and compresses the breast implant; it is a painful complication that might distort either the breast implant, or the breast, or both.

The cause of capsular contracture is unknown, but the common incidence factors include bacterial contamination, device-shell rupture, filler leakage, and hematoma. The surgical implantation procedures that have reduced the incidence of capsular contracture include submuscular emplacement, the use of breast implants with a textured surface (polyurethane-coated);[69][70][71] limited pre-operative handling of the implants, limited contact with the chest skin of the implant pocket before the emplacement of the breast implant, and irrigation of the recipient site with triple-antibiotic solutions.[72][73]

The correction of capsular contracture might require an open capsulotomy (surgical release) of the collagen-fiber capsule, or the removal, and possible replacement, of the breast implant. Furthermore, in treating capsular contracture, the closed capsulotomy (disruption via external manipulation) once was a common maneuver for treating hard capsules, but now is a discouraged technique, because it can rupture the breast implant. Non-surgical treatments for collagen-fiber capsules include massage, external ultrasonic therapy, leukotriene pathway inhibitors such as zafirlukast (Accolate) or montelukast (Singulair), and pulsed electromagnetic field therapy (PEMFT).[74][75][76][77]

Repair and revision surgeries

When the woman is unsatisfied with the outcome of the augmentation mammoplasty; or when technical or medical complications occur; or because of the breast implants' limited product life (Class III medical device, in the U.S.), it is likely she might require replacing the breast implants. The common revision surgery indications include major and minor medical complications, capsular contracture, shell rupture, and device deflation.[58] Revision incidence rates were greater for breast reconstruction patients, because of the post-mastectomy changes to the soft-tissues and to the skin envelope of the breast, and to the anatomical borders of the breast, especially in women who received adjuvant external radiation therapy.[58] Moreover, besides breast reconstruction, breast cancer patients usually undergo revision surgery of the nipple-areola complex (NAC), and symmetry procedures upon the opposite breast, to create a bust of natural appearance, size, form, and feel. Carefully matching the type and size of the breast implants to the patient's pectoral soft-tissue characteristics reduces the incidence of revision surgery. Appropriate tissue matching, implant selection, and proper implantation technique, the re-operation rate was 3.0% at the 7-year-mark, compared with the re-operation rate of 20% at the 3-year-mark, as reported by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.[78][79]

Systemic disease and sickness

Since the 1990s, reviews of the studies that sought causal links between silicone-gel breast implants and systemic disease reported no link between the implants and subsequent systemic and autoimmune diseases.[66][80][81][82] Nonetheless, during the 1990s, thousands of women claimed sicknesses they believed were caused by their breast implants, including neurological and rheumatological health problems.

In the study Long-term Health Status of Danish Women with Silicone Breast Implants (2004), the national healthcare system of Denmark reported that women with implants did not risk a greater incidence and diagnosis of autoimmune disease, when compared to same-age women in the general population; that the incidence of musculoskeletal disease was lower among women with breast implants than among women who had undergone other types of cosmetic surgery; and that they had a lower incidence rate than like women in the general population.[83][84]

Follow-up longitudinal studies of these breast implant patients confirmed the previous findings on the matter.[85] European and North American studies reported that women who underwent augmentation mammoplasty, and any plastic surgery procedure, tended to be healthier and wealthier than the general population, before and after implantation; that plastic surgery patients had a lower standardized mortality ratio than did patients for other surgeries; yet faced an increased risk of death by lung cancer than other plastic surgery patients. Moreover, because only one study, the Swedish Long-term Cancer Risk Among Swedish Women with Cosmetic Breast Implants: an Update of a Nationwide Study (2006), controlled for tobacco smoking information, the data were insufficient to establish verifiable statistical differences between smokers and non-smokers that might contribute to the higher lung cancer mortality rate of women with breast implants.[86][87] The long-term study of 25,000 women, Mortality among Canadian Women with Cosmetic Breast Implants (2006), reported that the "findings suggest that breast implants do not directly increase mortality in women."[36]

The study Silicone gel Breast Implant Rupture, Extracapsular Silicone, and Health Status in a Population of Women (2001), reported increased incidences of fibromyalgia among women who suffered extracapsular silicone-gel leakage than among women whose breast implants neither ruptured nor leaked.[88] The study later was criticized as significantly methodologically flawed, and a number of large subsequent follow-up studies have not shown any evidence of a causal device–disease association. After investigating, the U.S. FDA has concluded "the weight of the epidemiological evidence published in the literature does not support an association between fibromyalgia and breast implants."[89][90] The systemic review study, Silicone Breast implants and Connective tissue Disease: No Association (2011) reported the investigational conclusion that “any claims that remain regarding an association between cosmetic breast implants and CTDs are not supported by the scientific literature”.[91]

Platinum toxicity

The manufacture of silicone breast implants requires the metallic element platinum (Pt, 78) as a catalyst to accelerate the transformation of silicone oil into silicone gel for making the elastomer silicone shells, and for making other medical-silicone devices.[92] The literature indicates that trace quantities of platinum leak from such types of silicone breast implant; therefore, platinum is present in the surrounding pectoral tissue(s). The rare pathogenic consequence is an accumulation of platinum in the bone marrow, from where blood cells might deliver it to nerve endings, thus causing nervous system disorders such as blindness, deafness, and nervous tics (involuntary muscle contractions).[92]

In 2002, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (U.S. FDA) reviewed the studies on the human biological effects of breast-implant platinum, and reported little causal evidence of platinum toxicity to women with breast implants.[93] Furthermore, in the journal Analytical Chemistry, the study "Total Platinum Concentration and Platinum Oxidation States in Body Fluids, Tissue, and Explants from Women Exposed to Silicone and Saline Breast Implants by IC-ICPMS" (2006) proved controversial for claiming to have identified previously undocumented toxic platinum oxidative states in vivo.[94] Later, in a letter to the readers, the editors of Analytical Chemistry published their concerns about the faulty experimental design of the study, and warned readers to “use caution in evaluating the conclusions drawn in the paper”.[95]

Furthermore, after reviewing the research data of the study "Total Platinum Concentration and Platinum Oxidation States in Body Fluids, Tissue, and Explants from Women Exposed to Silicone and Saline Breast Implants by IC-ICPMS", and other pertinent literature, the U.S. FDA reported that the data do not support the findings presented; that the platinum used in new-model breast implant devices likely is not ionized, and therefore is not a significant risk to the health of the women.[96]

Non-implant breast augmentation

Non-implant breast augmentation with injections of autologous fat grafts (adipocyte tissue) is indicated for women requiring breast reconstruction, defect correction, and the æsthetic enhancement of the bust.

- breast reconstruction: post-mastectomy re-creation of the breast(s); trauma-damaged tissues (blunt, penetrating), disease (breast cancer), and explantation deformity (empty breast-implant socket).

- congenital defect correction: micromastia, tuberous breast deformity, Poland's syndrome, etc.

- primary augmentation: the aesthetic enhancement (contouring) of the size, form, and feel of the breasts.

The operating room time of breast reconstruction, congenital defect correction, and primary breast augmentation procedures is determined by the indications to be treated.

The advent of liposuction technology facilitated medical applications of the liposuction-harvested fat tissue as autologous filler for injection to correct bodily defects, and for breast augmentation. Melvin Bircoll introduced the practice of contouring the breast and for correcting bodily defects with autologous fat grafts harvested by liposuction; and he presented the fat-injection method used for emplacing the fat grafts.[97][98] In 1987, the Venezuelan plastic surgeon Eduardo Krulig emplaced fat grafts with a syringe and blunt needle (lipo-injection), and later used a disposable fat trap to facilitate the collection and to ensure the sterility of the harvested adipocyte tissue.[99][100]

To emplace the grafts of autologous fat-tissue, doctors J. Newman and J. Levin designed a lipo-injector gun with a gear-driven plunger, which allowed the even injection of autologous fat-tissue to the desired recipient sites. The control afforded by the lipo-injector gun assisted the plastic surgeon in controlling excessive pressure to the fat in the barrel of the syringe, thus avoiding over-filling the recipient site.[101] The later-design lipo-injector gun featured a ratchet-gear operation that afforded the surgeon greater control in accurately emplacing grafts of autologous fat to the recipient site; a trigger action injected 0.1 cm3 of filler.[102] Since 1989, most non-surgical, fat-graft augmentations of the breast employ adipocyte fat from sites other than the breast, up to 300 ml of fat in three equal injections, is placed into the subpectoral space and the intrapectoral space of the pectoralis major muscle, as well as the submammary space, to achieve a breast outcome of natural appearance and contour.[103]

Autologous fat grafting

The technique of autologous fat-graft injection to the breast is applied for the correction of breast asymmetry or deformities, for post-mastectomy breast reconstruction (as a primary and as an adjunct technique), for the improvement of soft-tissue coverage of breast implants, and for the aesthetic enhancement of the bust. The careful harvesting and centrifugal refinement of the mature adipocyte tissue (injected in small aliquots) allows the transplanted fat tissue to remain viable in the breast, where it provides the anatomical structure and the hemispheric contour that cannot be achieved solely with breast implants or with corrective plastic surgery.

In fat-graft breast augmentation procedures, there is the risk that the adipocyte tissue grafted to the breast(s) can undergo necrosis, metastatic calcification, develop cysts, and agglomerate into palpable lumps. Although the cause of metastatic calcification is unknown, the post-procedure biological changes occurred to the fat-graft tissue resemble the tissue changes usual to breast surgery procedures such as reduction mammoplasty. The French study Radiological Evaluation of Breasts Reconstructed with Lipo-modeling (2005) indicates the therapeutic efficacy of fat-graft breast reconstruction in the treatment of radiation therapy damage to the chest, the incidental reduction of capsular contracture, and the improved soft-tissue coverage of breast implants.[104][105][106][107][108][109]

The study Fat Grafting to the Breast Revisited: Safety and Efficacy (2007) reported successful transfers of body fat to the breast, and proposed the fat-graft injection technique as an alternative (i.e., non-implant) augmentation mammoplasty procedure instead of the surgical procedures usual for effecting breast augmentation, breast defect correction, and breast reconstruction.

Structural fat-grafting was performed either to one breast or to both breasts of the 17 women; the age range of the women was 25–55 years; the mean age was 38.2 years; the average volume of a tissue-graft was 278.6 cm3 of fat per operation, per breast.

The pre-procedure mammograms were negative for malignant neoplasms. In the 17-patient cohort, it was noted that two women developed breast cancer (diagnosed by mammogram) post-procedure: one at 12 months, and the other at 92 months.[110] Further, the study Cell-assisted Lipotransfer for Cosmetic Breast Augmentation: Supportive Use of Adipose-Derived Stem/Stromal Cells (2007), an approximately 40-woman cohort indicated that the inclusion of adipose stem cells in the grafts of adipocyte fat increased the rate of corrective success of the autologous fat-grafting procedure.[111]

Fat grafting techniques

- Fat harvesting and contouring

The centrifugal refinement of the liposuction-harvested adipocyte tissues removes blood products and free lipids to produce autologous breast filler. The injectable filler-fat is obtained by centrifuging (spinning) the fat-filled syringes for sufficient time to allow the serum, blood, and oil (liquid fat) components to collect, by density, apart from the refined, injection-quality fat.[112] To refine the fat for facial injection quality, the fat-filled syringes are centrifuged for 1.0 minute at 2,000 RPM, which separates the unnecessary solution, leaving refined filler-fat.[113] Moreover, centrifugation at 10,000 RPM for 10 minutes produces a "collagen graft"; the histologic composition of which is cell residues, collagen fibres, and 5.0 percent intact fat cells. Furthermore, because the patient's body naturally absorbs some of the fat grafts, the breasts maintain their contours and volumes for 18–24 months.[114][115]

In the study Fat Grafting to the Breast Revisited: Safety and Efficacy (2007), the investigators reported that the autologous fat was harvested by liposuction, using a 10-ml syringe attached to a two-hole Coleman harvesting cannula; after centrifugation, the refined breast filler fat was transferred to 3-ml syringes. Blunt infiltration cannulas were used to emplace the fat through 2-mm incisions; the blunt cannula injection method allowed greater dispersion of small aliquots (equal measures) of fat, and reduced the possibility of intravascular fat injection; no sharp needles are used for fat-graft injection to the breasts. The 2-mm incisions were positioned to allow the infiltration (emplacement) of fat grafts from at least two directions; a 0.2 ml fat volume was emplaced with each withdrawal of the cannula.[116]

The breasts were contoured by layering the fat grafts into different levels within the breast, until achieving the desired breast form. The fat-graft injection technique allows the plastic surgeon precise control in accurately contouring the breast – from the chest wall to the breast skin envelope – with subcutaneous fat grafts to the superficial planes of the breast. This greater degree of breast sculpting is unlike the global augmentation realised with a breast implant emplaced below the breast or below the pectoralis major muscle, respectively expanding the retromammary space and the retropectoral space. The greatest proportion of the grafted fat usually is infiltrated to the pectoralis major muscle, then to the retropectoral space, and to the prepectoral space, (before and behind the pectoralis major muscle). Moreover, although fat grafting to the breast parenchyma usually is minimal, it is performed to increase the degree of projection of the bust.[110]

Fat-graft injection

The biologic survival of autologous fat tissue depends upon the correct handling of the fat graft, of its careful washing (refinement) to remove extraneous blood cells, and of the controlled, blunt-cannula injection (emplacement) of the refined fat-tissue grafts to an adequately vascularized recipient site. Because the body resorbs some of the injected fat grafts (volume loss), compensative over-filling aids in obtaining a satisfactory breast outcome for the patient; thus the transplantation of large-volume fat grafts greater than required, because only 25–50 percent of the fat graft survives at 1-year post-transplantation.[117]

The correct technique maximizes fat graft survival by minimizing cellular trauma during the liposuction harvesting and the centrifugal refinement, and by injecting the fat in small aliquots (equal measures), not clumps (too-large measures). Injecting minimal-volume aliquots with each pass of the cannula maximizes the surface area contact, between the grafted fat-tissue and the recipient breast-tissue, because proximity to a vascular system (blood supply) encourages histologic survival and minimizes the potential for fat necrosis.[110] Transplanted autologous fat tissue undergoes histologic changes like those undergone by a bone transplant; if the body accepts the fat-tissue graft, it is replaced with new fat tissue, if the fat-graft dies it is replaced by fibrous tissue. New fat tissue is generated by the activity of a large, wandering histocyte-type cell, which ingests fat and then becomes a fat cell.[118] When the breast-filler fat is injected to the breasts in clumps (too-large measures), fat cells emplaced too distant from blood vessels might die, which can lead to fat tissue necrosis, causing lumps, calcifications, and the eventual formation of liponecrotic cysts.

The operating room time required to harvest, refine, and emplace fat to the breasts is greater than the usual 2-hour OR time; the usual infiltration time was approximately 2-hours for the first 100 cm3 volume, and approximately 45 minutes for injecting each additional 100 cm3 volume of breast-filler fat. The technique for injecting fat grafts for breast augmentation allows the plastic surgeon great control in sculpting the breasts to the required contour, especially in the correction of tuberous breast deformity. In which case, no fat-graft is emplaced beneath the nipple-areola complex (NAC), and the skin envelope of the breast is selectively expanded (contoured) with subcutaneously emplaced body-fat, immediately beneath the skin. Such controlled contouring selectively increased the proportional volume of the breast in relation to the size of the nipple-areola complex, and thus created a breast of natural form and appearance; greater verisimilitude than is achieved solely with breast implants. The fat-corrected, breast-implant deformities, were inadequate soft-tissue coverage of the implant(s) and capsular contracture, achieved with subcutaneous fat-grafts that hid the implant-device edges and wrinkles, and decreased the palpability of the underlying breast implant. Furthermore, grafting autologous fat around the breast implant can result in softening the breast capsule.[119]

External tissue expansion

The successful outcome of fat-graft breast augmentation is enhanced by achieving a pre-expanded recipient site to create the breast-tissue matrix that will receive grafts of autologous adipocyte fat. The recipient site is expanded with an external vacuum tissue-expander applied upon each breast. The biological effect of negative pressure (vacuum) expansion upon soft tissues derives from the ability of soft tissues to grow when subjected to controlled, distractive, mechanical forces. (see distraction osteogenesis) The study reported the technical effectiveness of recipient-site pre-expansion. In a single-group study, 17 healthy women (aged 18–40 years) wore a brassiere-like vacuum system that applied a 20-mmHg vacuum (controlled, mechanical, distraction force) to each breast for 10–12 hours daily for 10 weeks. Pre- and post-procedure, the breast volume (size) was periodically measured; likewise, a magnetic resonance image (MRI) of the breast-tissue architecture and water density was taken during the same phase of the patient's menstrual cycle; of the 17-woman study group, 12 completed the study, and 5 withdrew, because of non-compliance with the clinical trial protocol.[120]

The breast volume (size) of all 17 women increased throughout the 10-week treatment period, the greatest increment was at week 10 (final treatment) – the average volume increase was 98+/–67 percent over the initial breast-size measures. Incidences of partial recoil occurred at 1-week post-procedure, with no further, significant, breast volume decrease afterwards, nor at the follow-up treatment at 30-weeks post-procedure. The stable, long-term increase in breast size was 55 percent (range 15–115%). The MRI visualizations of the breasts showed no edema, and confirmed the proportionate enlargement of the adipose and glandular components of the breast-tissue matrices. Furthermore, a statistically significant decrease in body weight occurred during the study, and self-esteem questionnaire scores improved from the initial-measure scores.[120]

Because external vacuum expansion of the recipient-site tissues permits injecting large-volume fat grafts (+300 cc) to correct defects and enhance the bust, the histologic viability of the breast filler (adipocyte fat) and its volume must be monitored and maintained. The long-term, volume maintenance data reported in Breast Augmentation using Pre-expansion and Autologous Fat Transplantation: a Clinical Radiological Study (2010) indicate the technical effectiveness of external tissue expansion of the recipient site for a 25-patient study group, who had 46 breasts augmented with fat grafts. The indications included micromastia (underdevelopment), explantation deformity (empty implant pocket), and congenital defects (tuberous breast deformity, Poland's syndrome).[121]

Pre-procedure, every patient used external vacuum expansion of the recipient-site tissues to create a breast tissue matrix to be injected with autologous fat grafts of adipocyte tissue, refined via low G-force centrifugation. Pre- and post-procedure, the breast volumes were measured; the patients underwent pre-procedure and 6-month post-procedure MRI and 3D volumetric imaging examinations. At six months post-procedure, each woman had a significant increase in breast volume, ranging 60–200 percent, per the MRI (n=12) examinations. The size, form, and feel of the breasts was natural; post-procedure MRI examinations revealed no oil cysts or abnormality (neoplasm) in the fat-augmented breasts. Moreover, given the sensitive, biologic nature of breast tissue, periodic MRI and 3-D volumetric imaging examinations are required to monitor the breast-tissue viability and the maintenance of the large volume (+300 cc) fat grafts.[121]

Post-mastectomy procedures

Surgical post-mastectomy breast reconstruction requires general anaesthesia, cuts the chest muscles, produces new scars, and requires a long post-surgical recovery for the patient. The surgical emplacement of breast implant devices (saline or silicone) introduces a foreign object to the patient's body (see capsular contracture). The TRAM flap (Transverse Rectus Abdominis Myocutaneous flap) procedure reconstructs the breast using an autologous flap of abdominal, cutaneous, and muscle tissues. The latissimus myocutaneous flap employs skin fat and muscle harvested from the back, and a breast implant. The DIEP flap (Deep Inferior Epigastric Perforators) procedure uses an autologous flap of abdominal skin and fat tissue.[122]

Post-mastectomy fat-graft reconstruction

The reconstruction of the breast(s) with grafts of autologous fat is a non-implant alternative to further surgery after a breast cancer surgery, be it a lumpectomy or a breast removal – simple (total) mastectomy, radical mastectomy, modified radical mastectomy, skin-sparing mastectomy, and subcutaneous (nipple sparing) mastectomy. The breast is reconstructed by first applying external tissue expansion to the recipient-site tissues (adipose, glandular) to create a breast-tissue matrix that can be injected with autologous fat grafts (adipocyte tissue); the reconstructed breast has a natural form, look, and feel, and is generally sensate throughout and in the nipple-areola complex (NAC).[122] The reconstruction of breasts with fat grafts requires a three-month treatment period – begun after 3–5 weeks of external vacuum expansion of the recipient-site tissues. The autologous breast-filler fat is harvested by liposuction from the patient's body (buttocks, thighs, abdomen), is refined and then is injected (grafted) to the breast-tissue matrices (recipient sites), where the fat will thrive.

One method of non-implant breast reconstruction is initiated at the concluding steps of the breast cancer surgery, wherein the oncological surgeon is joined by the reconstructive plastic surgeon, who immediately begins harvesting, refining, and seeding (injecting) fat grafts to the post-mastectomy recipient site. After that initial post-mastectomy fat-graft seeding in the operating room, the patient leaves hospital with a slight breast mound that has been seeded to become the foundation tissue matrix for the breast reconstruction. Then, after 3–5 weeks of continual external vacuum expansion of the breast mound (seeded recipient-site) – to promote the histologic regeneration of the extant tissues (fat, glandular) via increased blood circulation to the mastectomy scar (suture site) – the patient formally undergoes the first fat-grafting session for the reconstruction of her breasts. The external vacuum expansion of the breast mound created an adequate, vascularised, breast-tissue matrix to which the autologous fat is injected; and, per the patient, such reconstruction affords almost-normal sensation throughout the breast and the nipple-areola complex. Patient recovery from non-surgical fat graft breast reconstruction permits her to resume normal life activities at 3-days post-procedure.[122]

Tissue engineering

- I. The breast mound

The breast-tissue matrix consists of engineered tissues of complex, implanted, biocompatible scaffolds seeded with the appropriate cells. The in-situ creation of a tissue matrix in the breast mound is begun with the external vacuum expansion of the mastectomy defect tissues (recipient site), for subsequent seeding (injecting) with autologous fat grafts of adipocyte tissue. A 2010 study, reported that serial fat-grafting to a pre-expanded recipient site achieved (with a few 2-mm incisions and minimally invasive blunt-cannula injection procedures), a non-implant outcome equivalent to a surgical breast reconstruction by autologous-flap procedure. Technically, the external vacuum expansion of the recipient-site tissues created a skin envelope as it stretched the mastectomy scar, and so generated a fertile breast-tissue matrix to which were injected large-volume fat grafts (150–600 ml) to create a breast of natural form, look, and feel.[123]

The fat graft breast reconstructions for 33 women (47 breasts, 14 irradiated), whose clinical statuses ranged from zero days to 30 years post-mastectomy, began with the pre-expansion of the breast mound (recipient site) with an external vacuum tissue-expander for 10 hours daily, for 10–30 days before the first grafting of autologous fat. The breast mound expansion was adequate when the mastectomy scar tissues stretched to create a 200–300 ml recipient matrix (skin envelope), that received a fat-suspension volume of 150–600 ml in each grafting session.[123]

At one week post-procedure, the patients resumed using the external vacuum tissue-expander for 10 hours daily, until the next fat grafting session; 2–5 outpatient procedures, 6–16 weeks apart, were required until the plastic surgeon and the patient were satisfied with the volume, form, and feel of the reconstructed breasts. The follow-up mammogram and MRI examinations found neither defects (necrosis) nor abnormalities (neoplasms). At six months post-procedure, the reconstructed breasts had a natural form, look, and feel, and the stable breast-volumes ranged 300–600 ml per breast. The post-procedure mammographies indicated normal, fatty breasts with well-vascularized fat, and few, scattered, benign oil cysts. The occurred complications included pneumothorax and transient cysts.[123]

- II. Explantation deformity

The autologous fat graft replacement of breast implants (saline and silicone) resolves medical complications such as: capsular contracture, implant shell rupture, filler leakage (silent rupture), device deflation, and silicone-induced granulomas, which are medical conditions usually requiring re-operation and explantation (breast implant removal). The patient then has the option of surgical or non-implant breast corrections, either replacement of the explanted breast implants or fat-graft breast augmentation. Moreover, because fat-grafts are biologically sensitive, they cannot survive in the empty implantation pocket, instead, they are injected to and diffused within the breast-tissue matrix (recipient site), replacing approximately 50% of the volume of the removed implant – as permanent breast augmentation. The outcome of the explantation correction is a bust of natural appearance; breasts of volume, form, and feel, that – although approximately 50% smaller than the explanted breast size – are larger than the original breast size, pre-procedure.

- III. Breast augmentation

The outcome of a breast augmentation with fat-graft injections depends upon proper patient selection, preparation, and correct technique for recipient site expansion, and the harvesting, refining, and injecting of the autologous breast filler fat. Technical success follows the adequate external vacuum expansion of the recipient-site tissues (matrix) before the injection of large-volume grafts (220–650 cc) of autologous fat to the breasts.[124] After harvesting by liposuction, the breast-filler fat was obtained by low G-force syringe centrifugation of the harvested fat to separate it, by density, from the crystalloid component. The refined breast filler then was injected to the pre-expanded recipient site; post-procedure, the patient resumed continual vacuum expansion therapy upon the injected breast, until the next fat grafting session. The mean operating room (OR) time was 2-hours, and there occurred no incidences of infection, cysts, seroma, hematoma, or tissue necrosis.[121]

The breast-volume data reported in Breast Augmentation with Autologous Fat Grafting: A Clinical Radiological Study (2010) indicated a mean increase of 1.2 times the initial breast volume, at six months post-procedure. In a two-year period, 25 patients underwent breast augmentation by fat graft injection; at three weeks pre-procedure, before the fat grafting to the breast-tissue matrix (recipient site), the patients were photographed, and examined via intravenous contrast MRI or 3-D volumetric imaging, or both. The breast-filler fat was harvested by liposuction (abdomen, buttocks, thighs), and yielded fat-graft volumes of 220–650 cm3 per breast. At six months post-procedure, the follow-up treatment included photographs, intravenous contrast MRI or 3-D volumetric imaging, or both. Each woman had an increased breast volume of 250 cm3 per breast, a mean volume increase confirmed by quantitative MRI analysis. The mean increase in breast volume was 1.2 times the initial breast volume measurements; the statistical difference between the pre-procedure and the six-month post-procedure breast volumes was (P< 00.0000007); the percentage increase basis of the breast volume was 60–80% of the initial, pre-procedure breast volume.[121]

Non-surgical procedures

In 2003, the Thai government endorsed a regimen of self-massage exercises as an alternative to surgical breast augmentation with breast implants. The Thai government enrolled more than 20 women in publicly funded courses for the teaching of the technique; nonetheless, beyond Thailand, the technique is not endorsed by the mainstream medical community. Despite the promising results of a six-month study of the therapeutic effectiveness of the technique, the research physician recommended to the participant women that they also contribute to augmenting their busts by gaining weight.[125]

Complications and limitations

Medical complications

In every surgical and nonsurgical procedure, the risk of medical complications exists before, during, and after a procedure, and, given the sensitive biological nature of breast tissues (adipocyte, glandular), this is especially true in the case of fat graft breast augmentation. Despite its relative technical simplicity, the injection (grafting) technique for breast augmentation is accompanied by post-procedure complications – fat necrosis, calcification, and sclerotic nodules – which directly influence the technical efficacy of the procedure, and of achieving a successful outcome. The Chinese study Breast Augmentation by Autologous Fat-injection Grafting: Management and Clinical analysis of Complications (2009), reported that the incidence of medical complications is reduced with strict control of the injection-rate (cm3/min) of the breast-filler volume being administered, and by diffusing the fat-grafts in layers to allow their even distribution within the breast tissue matrix. The complications occurred to the 17-patient group were identified and located with 3-D volumetric and MRI visualizations of the breast tissues and of any sclerotic lesions and abnormal tissue masses (malignant neoplasm). According to the characteristics of the defect or abnormality, the sclerotic lesion was excised and liquefied fat was aspirated; the excised samples indicated biological changes in the intramammary fat grafts – fat necrosis, calcification, hyalinization, and fibroplasia.[126]

The complications associated with injecting fat grafts to augment the breasts are like, but less severe, than the medical complications associated with other types of breast procedure. Technically, the use of minuscule (2-mm) incisions and blunt-cannula injection much reduce the incidence of damaging the underlying breast structures (milk ducts, blood vessels, nerves). Injected fat-tissue grafts that are not perfused among the tissues can die, and result in necrotic cysts and eventual calcifications – medical complications common to breast procedures. Nevertheless, a contoured abdomen for the patient is an additional benefit derived from the liposuction harvesting of the adipocyte tissue injected to the breasts. (see abdominoplasty)

Technical limitations

When the patient's body has insufficient adipocyte tissue to harvest as injectable breast filler, a combination of fat grafting and breast implants might provide the desired outcome. Although non-surgical breast augmentation with fat graft injections is not associated with implant-related medical complications (filler leakage, deflation, visibility, palpability, capsular contracture), the achievable breast volumes are physically limited; the large-volume, global bust augmentations realised with breast implants are not possible with the method of structural fat grafting. Global breast augmentation contrasts with the controlled breast augmentation of fat-graft injection, in the degree of control that the plastic surgeon has in achieving the desired breast contour and volume. The controlled augmentation is realised by infiltrating and diffusing the fat grafts throughout the breast; and it is feather-layered into the adjacent pectoral areas until achieving the desired outcome of breast volume and contour. Nonetheless, the physical fullness-of-breast achieved with injected fat-grafts does not visually translate into the type of buxom fullness achieved with breast implants; hence, patients who had plentiful fat-tissue to harvest attained a maximum breast augmentation of one bra cup size in one session of fat grafting to the breast.[110]

Breast cancer

Detection

A contemporary woman's lifetime probability of developing breast cancer is approximately one in seven;[127] yet there is no causal evidence that fat grafting to the breast might be more conducive to breast cancer than are other breast procedures; because incidences of fat tissue necrosis and calcification occur in every such procedure: breast biopsy, implantation, radiation therapy, breast reduction, breast reconstruction, and liposuction of the breast. Nonetheless, detecting breast cancer is primary, and calcification incidence is secondary; thus, the patient is counselled to learn self-palpation of the breast and to undergo periodic mammographic examinations. Although the mammogram is the superior diagnostic technique for distinguishing among cancerous and benign lesions to the breast, any questionable lesion can be visualized ultrasonically and magnetically (MRI); biopsy follows any clinically suspicious lesion or indeterminate abnormality appeared in a radiograph.[110]

Therapy

Breast augmentation via autologous fat grafts allows the oncological breast surgeon to consider conservative breast surgery procedures that usually are precluded by the presence of alloplastic breast implants, e.g. lumpectomy, if cancer is detected in an implant-augmented breast. In previously augmented patients, aesthetic outcomes cannot be ensured without removing the implant and performing mastectomy.[128][129] Moreover, radiotherapy treatment is critical to reducing cancerous recurrence and to the maximal conservation of breast tissue; yet, radiotherapy of an implant-augmented breast much increases the incidence of medical complications – capsular contracture, infection, extrusion, and poor cosmetic outcome.[110]

Post-cancer breast reconstruction

After mastectomy, surgical breast reconstruction with autogenous skin flaps and with breast implants can produce subtle deformities and deficiencies resultant from such global breast augmentation, thus the breast reconstruction is incomplete. In which case, fat graft injection can provide the missing coverage and fullness, and might relax the breast capsule. The fat can be injected as either large grafts or as small grafts, as required to correct difficult axillary deficiencies, improper breast contour, visible implant edges, capsular contracture, and tissue damage consequent to radiation therapy.[110]

References

- Cell-assisted Lipotransfer for Cosmetic Breast Augmentation: Supportive Use of Adipose-Derived Stem/Stromal Cells (2007) Yoshimura, K.; Sato, K.; Aoi, N.; Kurita, M.; Hirohi, T.; Harii, K. (2007). "Cell-Assisted Lipotransfer for Cosmetic Breast Augmentation: Supportive Use of Adipose-Derived Stem/Stromal Cells". Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 32 (1): 48–55, discussion 56–7. doi:10.1007/s00266-007-9019-4. PMC 2175019. PMID 17763894.

- Nichter, Larry S.; Hardesty, Robert A.; Anigian, Gregg M. (July 2018). "IDEAL IMPLANT Structured Breast Implants: Core Study Results at 6 Years". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 142 (1): 66–75. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000004460. PMC 6045953. PMID 29489559.

- Stevens WG, Hirsch EM, Stoker DA, Cohen R (2006). "In vitro Deflation of Pre-filled Saline Breast Implants". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 118 (2): 347–349. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000227674.65284.80. PMID 16874200. S2CID 41156555.

- Arion HG (1965). "Retromammary Prosthesis". C R Société Française de Gynécologie. 5.

- Eisenberg, TS (2009). "Silicone Gel Implants Are Back—So What?". American Journal of Cosmetic Surgery. 26: 5–7. doi:10.1177/074880680902600103. S2CID 136191732.

- Cronin TD, Gerow FJ (1963). "Augmentation Mammaplasty: A New "natural feel" Prosthesis". Excerpta Medica International Congress Series. 66: 41.

- Luu HM, Hutter JC, Bushar HF (1998). "A Physiologically based Pharmacokinetic Model for 2,4-toluenediamine Leached from Polyurethane foam-covered Breast Implants". Environ Health Perspect. 106 (7): 393–400. doi:10.2307/3434066. JSTOR 3434066. PMC 1533137. PMID 9637796.

- Hester TR Jr; Tebbetts JB; Maxwell GP (2001). "The Polyurethane-covered Mammary Prosthesis: Facts and Fiction (II): A Look Back and a "peek" Ahead". Clinical Plastic Surgery. 28 (3): 579–86. doi:10.1016/S0094-1298(20)32397-X. PMID 11471963.

- Brown, M. H.; Shenker, R.; Silver, S. A. (2005). "Cohesive silicone gel breast implants in aesthetic and reconstructive breast surgery". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 116 (3): 768–779, discussion 779–1. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000176259.66948.e7. PMID 16141814. S2CID 35392851.

- Fruhstorfer, B. H.; Hodgson, E. L.; Malata, C. M. (2004). "Early experience with an anatomical soft cohesive silicone gel prosthesis in cosmetic and reconstructive breast implant surgery". Annals of Plastic Surgery. 53 (6): 536–542. doi:10.1097/01.sap.0000134508.43550.6f. PMID 15602249. S2CID 24661896.

- Hedén, P.; Jernbeck, J.; Hober, M. (2001). "Breast augmentation with anatomical cohesive gel implants: The world's largest current experience". Clinics in Plastic Surgery. 28 (3): 531–552. doi:10.1016/S0094-1298(20)32393-2. PMID 11471959.

- Zannis, John (2017). Tales for Tagliacozzi: An Inside Look at Modern-Day Plastic Surgery. ISBN 9781524659073. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- "What types of breast implants are available?". American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

- Tortora, Gerard J. Introduction to the Human Body, Fifth Edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, 2001. p. 560.

- Berlin, C. M. (1994). "Silicone Breast Implants and Breast-feeding". Pediatrics. 94 (4 Pt 1): 546–549. PMID 7936870.

- Berlin, Cheston M., Jr. Silicone Breast Implants and Breastfeeding Archived 2010-12-31 at the Wayback Machine, Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, Pennsylvania; from Breastfeeding Abstracts. February 1996, Volume 15, Number 3, pp. 17–18.

- Breastfeeding after Breast Surgery Archived 2010-12-30 at the Wayback Machine, La Leche League (2009-09-05).

- Breastfeeding and Breast Implants Archived 2010-12-31 at the Wayback Machine, Selected Bibliography April 2003, LLLI Center for Breastfeeding Information.

- Beam, Christopher (2009-12-11). Inorganic Milk: Can Kendra Wilkinson breast-feed her baby even though she has implants? Archived 2016-05-07 at the Wayback Machine, Slate.com.

- Brinton L, Brown S, Colton T, Burich M, Lubin J (2000). "Characteristics of a Population of Women with Breast Implants Compared with Women Seeking other Types of Plastic Surgery". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 105 (3): 919–927. doi:10.1097/00006534-200003000-00014. PMID 10724251. S2CID 32599107.

- Jacobsen, P. H.; Hölmich, L. R.; McLaughlin, J. K.; Johansen, C.; Olsen, J. H.; Kjøller, K.; Friis, S. (2004). "Mortality and Suicide Among Danish Women with Cosmetic Breast Implants". Archives of Internal Medicine. 164 (22): 2450–2455. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.22.2450. PMID 15596635.

- Young, V. L.; Nemecek, J. R.; Nemecek, D. A. (1994). "The efficacy of breast augmentation: Breast size increase, patient satisfaction, and psychological effects". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 94 (7): 958–969. doi:10.1097/00006534-199412000-00009. PMID 7972484. S2CID 753343.

- Crerand, C. E.; Franklin, M. E.; Sarwer, D. B. (2006). "Body Dysmorphic Disorder and Cosmetic Surgery". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 118 (7): 167e–180e. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000242500.28431.24. PMID 17102719. S2CID 8925060.

- Sarwer, D. B.; Larossa, D.; Bartlett, S. P.; Low, D. W.; Bucky, L. P.; Whitaker, L. A. (2003). "Body Image Concerns of Breast Augmentation Patients". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 112 (1): 83–90. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000066005.07796.51. PMID 12832880. S2CID 45574374.

- Chahraoui, K.; Danino, A.; Frachebois, C.; Clerc, A. S.; Malka, G. (2006). "Chirurgie esthétique et qualité de vie subjective avant et quatre mois après l'opération". Annales de Chirurgie Plastique et Esthétique. 51 (3): 207–210. doi:10.1016/j.anplas.2005.07.010. PMID 16181718.

- Cash, T. F.; Duel, L. A.; Perkins, L. L. (2002). "Women's psychosocial outcomes of breast augmentation with silicone gel-filled implants: A 2-year prospective study". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 109 (6): 2112–2121, discussion 2121–3. doi:10.1097/00006534-200205000-00049. PMID 11994621.

- Figueroa-Haas, C. L. (2007). "Effect of breast augmentation mammoplasty on self-esteem and sexuality: A quantitative analysis". Plastic Surgical Nursing. 27 (1): 16–36. doi:10.1097/01.PSN.0000264159.30505.c9. PMID 17356451. S2CID 23169107.

- "Important Information for Women About Breast Augmentation with Inamed Silicone Gel-Filled Implants" (PDF). 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-01-03. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- Handel, N.; Cordray, T.; Gutierrez, J.; Jensen, J. A. (2006). "A Long-Term Study of Outcomes, Complications, and Patient Satisfaction with Breast Implants". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 117 (3): 757–767, discussion 767–72. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000201457.00772.1d. PMID 16525261. S2CID 15228702.

- They Need Bosoms, too – Women Weight Lifters Archived 2016-10-22 at the Wayback Machine, Cosmeticsurgery.com

- "Breast Implants Linked with Suicide in Study". Reuters. 2007-08-08.

- Manning, Anita (2007-08-06). "Breast Implants Linked to Higher Suicide Rates". USA Today. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- Brinton, L. A.; Lubin, J. H.; Burich, M. C.; Colton, T.; Hoover, R. N. (2001). "Mortality among augmentation mammoplasty patients". Epidemiology. 12 (3): 321–326. doi:10.1097/00001648-200105000-00012. PMID 11337605.

- Koot, V. C. M.; Peeters, P. H.; Granath, F.; Grobbee, D. E.; Nyren, O. (2003). "Total and cause specific mortality among Swedish women with cosmetic breast implants: Prospective study". BMJ. 326 (7388): 527–528. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7388.527. PMC 150462. PMID 12623911.

- Pukkala, E.; Kulmala, I.; Hovi, S. L.; Hemminki, E.; Keskimäki, I.; Lipworth, L.; Boice, J. D.; McLaughlin, J. K.; McLaughlin, J. K. (2003). "Causes of Death Among Finnish Women with Cosmetic Breast Implants, 1971–2001". Annals of Plastic Surgery. 51 (4): 339–342, discussion 342–4. doi:10.1097/01.sap.0000080407.97677.A5. PMID 14520056. S2CID 34929987.

- Villenueve PJ, et al. (June 2006). "Mortality among Canadian Women with Cosmetic Breast Implants". American Journal of Epidemiology. 164 (4): 334–341. doi:10.1093/aje/kwj214. PMID 16777929.

- Brinton, L. A.; Lubin, J. H.; Murray, M. C.; Colton, T.; Hoover, R. N. (2006). "Mortality Rates Among Augmentation Mammoplasty Patients". Epidemiology. 17 (2): 162–169. doi:10.1097/01.ede.0000197056.84629.19. PMID 16477256. S2CID 22285852.

- National Plastic Surgery Procedural Statistics, 2006. Arlington Heights, Illinois, American Society of Plastic Surgeons, 2007

- Nauert, Rick. (2007-03-23) Plastic Surgery Helps Self-Esteem | Psych Central News. Psychcentral.com. Retrieved on 2012-07-15.

- "Brustvergrösserung". plasticsurgerydubaiuae.com. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- Kearney, Robert. "Breast Augmentation". Robert Kearney MD FACS. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- Johnson, G. W.; Christ, J. E. (1993). "The endoscopic breast augmentation: The transumbilical insertion of saline-filled breast implants". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 92 (5): 801–808. doi:10.1097/00006534-199392050-00004. PMID 8415961.

- Wallach, S. G. (2004). "Maximizing the Use of the Abdominoplasty Incision". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 113 (1): 411–417, discussion 417. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000091422.11191.1A. PMID 14707667. S2CID 44430032.

- Graf RM, et al. (2003). "Subfascial Breast Implant: A New Procedure". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 111 (2): 904–908. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000041601.59651.15. PMID 12560720.

- Tebbetts JB (2004). "Does Fascia Provide Additional, Meaningful Coverage over a Breast Implant?". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 113 (2): 777–779. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000104516.13465.96. PMID 14758271.

- Tebbetts T (2002). "A System for Breast Implant Selection Based on Patient Tissue Characteristics and Implant-soft tissue Dynamics". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 109 (4): 1396–1409. doi:10.1097/00006534-200204010-00030. PMID 11964998. S2CID 33418455.

- Pacik, P.; Nelson, C.; Werner, C. (2008). "Pain Control in Augmentation Mammaplasty: Safety and Efficacy of Indwelling Catheters in 644 Consecutive Patients". Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 28 (3): 279–284. doi:10.1016/j.asj.2008.02.001. PMID 19083538.

- Pacik, P.; Nelson, C.; Werner, C. (2008). "Pain Control in Augmentation Mammaplasty Using Indwelling Catheters in 687 Consecutive Patients: Data Analysis". Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 28 (6): 631–641. doi:10.1016/j.asj.2008.09.001. PMID 19083591.