Brachypelma hamorii

Brachypelma hamorii is a species of tarantula found in Mexico.[2] It has been confused with B. smithi; both have been called Mexican redknee tarantulas.[3] Many earlier sources referring to B. smithi either do not distinguish between the two species or relate to B. hamorii. B. hamorii is a terrestrial tarantula native to the western faces of the Sierra Madre Occidental and Sierra Madre del Sur mountain ranges in the Mexican states of Colima, Jalisco, and Michoacán.[3][4] The species is a large spider, adult females having a total body length over 50 mm (2 in) and males having legs up to 75 mm (3 in) long. Mexican redknee tarantulas are a popular choice for enthusiasts. Like most tarantulas, it has a long lifespan.[5]

| Brachypelma hamorii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Class: | Arachnida |

| Order: | Araneae |

| Infraorder: | Mygalomorphae |

| Family: | Theraphosidae |

| Genus: | Brachypelma |

| Species: | B. hamorii |

| Binomial name | |

| Brachypelma hamorii Tesmoingt, Cleton & Verdez, 1997[2] | |

Description

Brachypelma hamorii is a large spider. A sample of seven females had a total body length (excluding chelicerae and spinnerets) in the range 52–54 mm (2.0–2.1 in). A sample of 11 males was slightly smaller, with a total body length in the range 46–52 mm (1.8–2.0 in). Although males have slightly shorter bodies, they have longer legs. The fourth leg is the longest, measuring 75 mm (3.0 in) in the type male and 67 mm (2.6 in) in a female. The legs and palps are black to reddish black with three distinctly colored rings, deep orange on the part of the patellae closest to the body with pale orange–yellow further away, pale orange–yellow on the lower part of the tibiae, and yellowish-white at the end of the metatarsi. Adult males have light greyish-red around the border of the carapace with a darker reddish-black marking from the middle of the carapace to the front of the head; the upper surface of the abdomen is black. Adult females vary more in carapace color and pattern. The carapace may be mainly black with a brownish-pink border, or the dark area may be broken up into a "starburst" pattern with pale orange–yellow elsewhere.[3]

Taxonomy

Brachypelma hamorii was initially misidentified as the very similar B. smithi, a species originally described in 1897. In 1968, the holotype of B. smithi was found to be an immature male, and in 1994, A. M. Smith redescribed B. smithi using two adult specimens. The specimens cannot now be found, but his description makes it clear that they actually belonged to what is now B. hamorii, not B. smithi.[3] B. hamorii was first described by Marc Tesmoingt, Frédéric Cleton and Jean Verdez in 1997.[2] They stated that it was close to B. smithi, but could be distinguished by a number of characteristics, including the spermathecae of the females.[6] However, following Smith's description, B. hamorii continued to be misidentified as B. smithi until the situation was clarified by J. Mendoza and O. Francke in 2017.[3]

The two species have very similar color patterns. When viewed from above, the chelicerae of B. hamorii have two brownish-pink bands on a greyish background, not visible on all individuals. B. smithi lacks these bands. Mature males of the two species can be distinguished by the shape of the palpal bulb. When viewed retrolaterally, the palpal bulb of B. hamorii is narrower and less straight than the broad, spoon-shaped one of B. smithi. It also has a narrower keel at the apex. In mature females of B. hamorii, the baseplate of the spermatheca is elliptical, rather than divided and subtriangular as in B. smithi; also, the ventral face of the spermatheca is smooth rather than striated.[3]

DNA barcoding

DNA barcoding has been applied to Mexican species of Brachypelma. In this approach, a portion of about 650 base pairs of the mitochondrial gene cytochrome oxidase I is used, primarily to identify existing species, but also sometimes to support a separation between species. In 2017, Mendoza and Francke showed that although B. hamorii and B. smithi are similar in external appearance, they are clearly distinguished by their DNA barcodes.[3]

Longevity

B. hamorii grows very slowly and matures relatively late. The females of this species can live up to 30 years, but the males tend to live for only 5 years or so.[7]

Molting

Like all tarantulas, B. hamorii is an arthropod, and must go through a molting process to grow. Molting serves several purposes, such as renewing the tarantula's outer cover (shell) and replacing missing appendages. As tarantulas grow, they regularly molt (shed their skin), on multiple occasions during the year, depending on the tarantula's age.[8] Since the exoskeleton cannot stretch, it must be replaced by a new one from beneath for the tarantula to grow. A tarantula may also regenerate lost appendages gradually, with each succeeding molt. Prior to molting, the spider becomes sluggish and stops eating to conserve as much energy as possible. Its abdomen darkens; this is the new exoskeleton beneath. Normally, the spider turns on its back to molt and stays in that position for several hours, as it pushes fluids just beneath its old exoskeleton and wiggles its limbs to loosen off the old and reveal the new exoskeleton. Once this has been accomplished, the tarantula does not eat for several days to weeks, and not uncommonly for up to a month after a molt, as its fangs are still soft; the fangs are also part of the exoskeleton and are shed with the rest of the skin.[9] The whole process can take several hours and sheaths the tarantula with a moist, new skin in place of an old, faded one.

Behavior

Like most New World tarantulas, they kick urticating hairs from their abdomens and their back legs if disturbed, rather than bite. They are only slightly venomous to humans and are considered extremely docile, though, as with all tarantulas, their large fangs can cause very painful puncture wounds, which can lead to secondary bacterial infection if not properly treated and allergies may intensify with any bite.[10]

Distribution and habitat

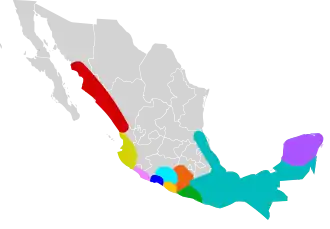

██ B. hamorii

██ B. smithi

These two were formerly often treated as the same species under the name B. smithi.

B. hamorii and the very similar B. smithi are found along the Pacific Coast of Mexico on opposite sides of the Balsas River basin as it opens onto the Pacific. B. hamorii is found to the north, in the states of Colima, Jalisco, and Michoacán. The natural habitat of the species is in hilly deciduous tropical forests. It constructs or extends burrows under logs, rocks, and tree roots, among thorny shrubs and tall grass.[3]

Their burrows were described in 1999 by a source that did not distinguish between B. hamorii and B. smithi. The deep burrows keep them protected from predators, such as the white-nosed coati, and enable them to ambush passing prey. The females spend the majority of their lives in their burrows, which are typically located in, or not far from, vegetation, and consist of a single entrance with a tunnel leading to one or two chambers. The entrance is just slightly larger than the body size of the spider. The tunnel, usually about three times the tarantula's leg span in length, leads to a chamber that is large enough for the spider to safely molt. Further down the burrow, via a shorter tunnel, a larger chamber is located where the spider rests and eats its prey. When the tarantula needs privacy, e.g. when molting or laying eggs, the entrance is sealed with silk, sometimes supplemented with soil and leaves.[4]

Conservation

In 1985, B. smithi (then not distinguished from B. hamorii) was placed on CITES Appendix II.[11] Wild-caught specimens shipped for the Chinese market were decreasing in size. The smaller sizes were suspected to be a consequence of a declining population due to excessive export. Exporting is not the only threat, though; some local people have reportedly made a habit of killing these spiders in a nearly systematic way using pesticides, pouring gasoline into burrows, or simply killing migrating spiders on sight.[10] The reasons for these actions seem to be an irrational fear based on myth surrounding B. hamorii and related species.[10] Thus, whether the listing strengthened the wild population or not remains uncertain. The species has been bred successfully in captivity.[10] In 1994, all remaining Brachypelma species were added to Appendix II.[11] Large numbers of Mexican redknee tarantulas caught in the wild continue to be smuggled out of Mexico. At least 3,000 specimens of Mexican tarantulas were reported to have been sent to the United States or Europe a few years prior to 2017, most of which were Mexican redknee tarantulas.[3]

References

- World Conservation Monitoring Centre (1996). "Brachypelma smithi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T8152A12893193. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T8152A12893193.en.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) (B. hamorii not then distinguished from B. smithi.)

- "Taxon details Brachypelma hamorii Tesmoingt, Cleton & Verdez, 1997". World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum Bern. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- Mendoza, J. & Francke, O. (2017). "Systematic revision of Brachypelma red-kneed tarantulas (Araneae: Theraphosidae), and the use of DNA barcodes to assist in the identification and conservation of CITES-listed species". Invertebrate Systematics. 31 (2): 157–179. doi:10.1071/IS16023.

- Locht, A.; Yáñez, M.; Vázquez, I. (1999). "Distribution and Natural History of Mexican Species of Brachypelma and Brachypelmides (Theraphosidae, Theraphosinae) with Morphological Evidence for Their Synonymy" (PDF). The Journal of Arachnology. 27: 196–200.

- "Tarantulas". National Wildlife Association. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- Tesmoingt, M.; Cleton, F. & Verdez, J.M. (1997). "Description de Brachypelma annitha n. sp. et de Brachypelma hamorii n. sp. mâles et femelles, nouvelles espèces proches de Brachypelma smithi (Cambridge, 1897) du Mexique". Arachnides (in French). 32 (8–20).

- "Mexican Red Knee Tarantula".

- Ramel, Gordon. "Caring for your Tarantula". Earthlife Web. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- Overton, Martin (April 4, 2007). "An Introduction to Tarantulas and Scorpions". arachnophiliac.info. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- Schultz, Stanley A. and Schultz, Marguerite J. (2009) The Tarantula Keeper's Guide: Comprehensive Information on Care, Housing, and Feeding (Revised Edition). Barrons.

- "Brachypelma smithi (F. O. Pickard-Cambridge, 1897): Documents", Species+, UNEP-WCMC & CITES Secretariat, retrieved 2017-09-22

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brachypelma hamorii. |

- Hijmensen, Eddy (2011). "Brachypelma hamorii". mantid.nl. Retrieved 2017-10-05. (Photographs taken in the wild.)

- Ondrej Rehak. "Photography of Brachypelma smithi". Tarantulas breeding.

- Mexican Red Knee Tarantula Care and guide