Boxers and Saints

Boxers and Saints are two companion graphic novel volumes written and illustrated by Gene Luen Yang, and colored by Lark Pien.[1] The publisher First Second Books released them on September 10, 2013. Together the two volumes have around 500 pages.[2]

| Boxers and Saints | |

|---|---|

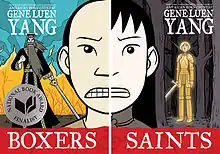

The cover of Boxers (left) and the cover of Saints (right), respectively. | |

| Date | 2013 |

| Publisher | First Second Books |

| Creative team | |

| Writer | Gene Luen Yang |

| Colorist | Lark Pien |

Boxers follows the story of Little Bao, a boy from Shan-tung (Shandong) who becomes a leader of the Boxer Rebellion.[3] Saints follows the story of "Four-Girl", a girl from the same village who becomes a Catholic, adopts the name "Vibiana", and hopes to attain the glory of Joan of Arc.

One book cover shows the left half of Bao's face with Qin Shi Huangdi and the other shows the right half of Vibiana's face with Joan of Arc. Together the covers portray a divided China.[4]

Development

Yang said that he wanted to do two volumes because he was not sure which side in the conflict were "good" or "bad" and he noticed connections between contemporary terrorists and the Boxers. Yang said "So in a lot of ways, I was trying to write the story of a young man who was essentially a terrorist, and I wanted him to be sympathetic, but I also didn't want the book to feel like I was condoning terrorism. So it was kind of a fine line."[2] He explained that he needed two different characters so the reader can "see everything through".[2]

Yang took six years to make the books. The first one or two years went into research.[2] He visited a library on a university campus to read books and compile notes. He visited the library once weekly for a period of one year.[5] Much of the research came from The Origins of the Boxer Uprising by Joseph Esherick.[2] He also visited an archive in Vanves, France made by the Jesuits; this archive included photos depicting violence during the Boxer rebellion, causing Yang to conclude that he needed to portray the said violence in his works.[6] So he himself and his readers could stomach the violence, Yang deliberately used a cartoonish and simple manner of illustration.[7]

The books were different lengths due to the differing natures of the respective stories. Yang stated that he encountered more difficulty writing Saints, in which the Christians stay in the same place and defend themselves, compared to Boxers, in which the characters go on an adventure.[5] The reason was that he wanted to find a visually interesting way to present the converts' internal struggles.[1] Yang outlined both books together and made the volumes separate.[8] He scripted and drew the two volumes separately, scripting Boxers first, then simultaneously scripting Saints while drawing Boxers, and finally drawing Saints. He worked on an unrelated superhero comic in-between drawing the two volumes to deal with his emotions.[5] Yang decided that a reader needed to be able to enjoy each individual book as a story of its own and not only together, so he gave the beginning-middle-end narrative structure to each.[9]

Yang described Boxers and Saints "definitely historical fiction".[2] In Boxers Yang began including more history as the characters reach Peking (Beijing).[2] The author said that his process in making the story was creating Bao, taking "just the bits and pieces that we do know about the beginnings of the Boxer Rebellion and weave it into his fictional life story."[2] In Saints Yang modeled the style off of American autobiographical comics, and the color scheme of Saints is far more limited than that of Boxers.[1]

Since many older American comic books used gibberish writing to portray foreign languages and since Yang wished to use the point of view of the Chinese, he decided that doing this for characters speaking non-Chinese languages would show how the Chinese considered them to be foreign.[7]

The font used for the books' captions was derived from the handwriting style of Yang's wife.[1]

Analysis

Wesley Yang of The New York Times wrote that "Despite the ostensibly evenhanded way Yang presents opposed perspectives, it’s clear he views the Boxer Rebellion as a series of massacres conducted by xenophobes who wound up harming the very culture they had pledged to protect."[10]

Dan Solomon of The Austin Chronicle wrote that the books are "very personal and character-driven, which isn't necessarily what you might anticipate when you have 500 pages in front of you about the Boxer Rebellion."[2]

Sheng-mei Ma, author of Sinophone-Anglophone Cultural Duet, stated that Saints is overall a more comedic work than Boxers and that the scenes of Vibiana being bored of Christian history shows "self-depreciating humor" from the Roman Catholic author.[11]

Characters

- Lee Bao[12] or "Little Bao" - Becomes the leader of the boxer rebellion. Bao grows up in Shan-tung and starts a rebellion after his fellow villagers are killed by imperial authorities acting under the direction of foreign powers. As Bao continues his quest, he begins committing more gruesome killings. His given name means "treasure".[13] Jee Yoon Lee of Hyphen Magazine wrote that "As the story draws to an end, Yang shows Bao as a morally complicated hero whose decisions expose the inevitable tragedy of civil warfare."[14]

- Yang wrote that he wanted to make his actions understandable but he did not want to justify them.[8] Yang stated "The Boxers have a lot in common with many of today's extremist movements in the Middle East. Little Bao would probably be labeled a terrorist if he were real and alive today."[8] Yang stated that he did not want to have the comic approve of terrorism, but he also wanted Bao to be a sympathetic character.[2] Sheng-mei Ma stated that since Bao shows excitement over Chinese culture, Bao serves as the "alter ego" of the U.S.-born Yang, who would find Chinese history to be exotic from his point of view.[11]

- Four-Girl/Vibiana - Chinese girl who converts to Catholicism. She was named "Four-Girl" due to her birth order. The character for four (Chinese: 四; pinyin: sì) sounds similar to that of "death" (死; sǐ) in Chinese, so her name has a negative connotation. Many people around her call her "devil" so she thinks of herself one. She stumbles onto a group of Catholics, thinking it is "devil training". She initially comes for food, but becomes a Catholic and does missionary work.[14] Bao kills her when she refuses to renounce Catholicism. Vibiana's inspiration was a relative of Yang who had been mistreated by her family due to her birth date, as it was unlucky in Chinese culture, who converted to Catholicism.[1] Sheng-mei Ma states that the comedic scenes of Vibiana being bored with Christian stories reflects Yang's familiarity with Christianity, which a typical American would have.[11]

- Red Lantern Chu - A cooking oil salesperson and martial arts master, Chu serves as Bao's mentor. Yang found Chu in the book The Origins of the Boxer Uprising.[2]

- Kong - A former thief, Kong and Vibiana have an odd relationship. Kong eventually tells Vibiana about his past, and how he ended up at the Semerian. He explains how he got his rat whisker scars, and why he is indebted to the priest, Father Bey. Vibiana suggest marriage teasingly. He later proposes, but she rejects him, saying she was over the idea, after hearing about the boxers, and is not willing to marry at such hard times, but indicates that she may have feelings for him. Kong then, (after some convincing) teaches her how to fight, so that she can be a Maiden Warrior. Kong later dies, shot in the head.

- Mei-wen - Bao's love interest and leader of the Red Lanterns, treasures the ancient Hanlin Academy library in Peking (Beijing). After Bao sets the library on fire, Mei-wen harshly criticizes him.[14] Mei-wen goes into the library with a foreign scholar and attempts to salvage books until the library collapses, killing her.

- Father Bey - A French missionary working in China. Disgusted by church corruption in his own country, he decided to go to China after hearing largely false propaganda about Chinese religion. He first appears in Bao's village and smashes the idol of the local harvest god. After seeing this, Bao grows up with a general hatred of Europeans. Four-Girl, however, is inspired by his action to join the church and become a 'devil' herself. When she runs away from home Father Bey allows her to travel with him. He is eventually killed by the Society, along with all of his congregation. He was based on several missionaries spreading Catholicism in China.[5]

- Dr. Won - An acupuncturist in Bao and Four-Girl's village who converts to Catholicism. He is a gentle man who embraces the non-violent side of his religion. He becomes Four-Girl's friend and introduces her to the Catholic faith. He introduces her to Father Bey when she tells him of her vision of Joan of Arc, and encourages her actions afterward. Father Bey, however, rejects Dr. Won when he finds he is an opium addict. Vibiana loses faith in him when she discovers this. He is killed by the Society trying to defend Father Bey. He is based on Saint Mark Ji Tianxiang, one of the Martyr Saints of China.[5]

- Joan of Arc- Joan is the spirit of the French heroine Joan of Arc. She appears around Vibiana and guides her through Catholicism, even on the day that Vibiana is killed. Yang stated that Joan of Arc was a character in the story "because I was struck by this common humanity between the Europeans and the Chinese."[5] Yang compared Joan's battles against the English, done to free France from foreign rule, with the Boxers' fight against foreigners.[5]

- There is a raccoon character who serves as an evil spirit who tries to influence Vibiana to do harmful acts. Sheng-mei Ma suggested that the raccoon reflected Yang's western background as raccoons are not common in Chinese stories.[15]

Awards and nominations

- National Book Awards Finalist, Young People's Literature 2013 [16]

- Booklist Top 10 Religion and Spirituality Books for Youth 2013 [17]

- School Library Journal Best Books of the Year 2013[18]

- 2013 Los Angeles Times Book Prize (Young adult literature) winner.[19]

See also

References

- Clark, Noelene (2013-09-10). "'Boxers & Saints': Gene Yang blends Chinese history, magical realism". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- Solomon, Dan. "One-Two Punch." Austin Chronicle. Friday September 20, 2013. Retrieved on October 4, 2013.

- Burns, Elizabeth. "Review: Boxers." School Library Journal. September 3, 2013. Retrieved on October 4, 2013.

- Ay-Leen the Peacemaker. "A Divided Nation in Gene Luen Yang’s Boxers & Saints." Tor Books, Macmillan Publishing. Monday August 26, 2013. Retrieved on October 4, 2013.

- Davidson, Danica (2013-09-06). "'THERE ARE ALWAYS TWO SIDES': GENE LUEN YANG ON 'BOXERS & SAINTS'". MTV. Retrieved 2018-03-15.

- Tarbox, Gwen Athene. "Violence and Tableau Vivant Effect in Clear Line Comics of Herge and Gene Luen Yang" (Chapter 9, in Section 3: Section Three: Talking Back to Hergé). In: Sanders, Joe Sutliff (editor). The Comics of Hergé: When the Lines Are Not So Clear. University Press of Mississippi, July 28, 2016. ISBN 1496807278, 9781496807274. Google Books PT 142.

- Roney, Tyler (2014-08-08). "Meanwhile, During the Boxer Rebellion…". The World of Chinese. The Commercial Press. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- Mayer, Peter. "'Boxers & Saints' & Compassion: Questions For Gene Luen Yang." National Public Radio. October 22, 2013. Retrieved on November 1, 2013.

- "Exclusive: Gene Luen Yang Announces New Boxers and Saints Graphic Novels". Wired. 2013-01-23. Retrieved 2018-07-31.

- Yang, Wesley (2013-10-13). "Views of the Rebellion Gene Luen Yang's 'Boxers' and 'Saints'". The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- Ma, Sheng-mei. Chapter 7 in Part II: Anglo. Sinophone-Anglophone Cultural Duet. Springer Company, July 26, 2017. ISBN 3319580337, 9783319580333. Chapter start p. 103. CITED: p. 113.

- "Boxers & Saints in the Classroom Part 1." Gene Luen Yang Official site. Retrieved on March 13, 2018.

- "TEACHERS’ GUIDE with Common Core State Standards Connections Boxers & Saints by Gene Luen Yang." Gene Luen Yang Official site. Retrieved on March 13, 2018. p. 5. "The protagonist of Boxers, Bao, on the other hand, is given a name that means treasure."

- Lee, Jee Yoon. "Books: The Complicated Non-Heroic Lives of Heroes." Hyphen Magazine. September 26, 2013. Retrieved on October 4, 2013.

- Ma, Sheng-mei. Chapter 7 in Part II: Anglo. Sinophone-Anglophone Cultural Duet. Springer Company, July 26, 2017. ISBN 3319580337, 9783319580333. Chapter start p. 103. CITED: p. 112.

- "2013 National Book Award Finalist, Young People's Literature". Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- Cooper, Ilene (November 15, 2013). Top 10 Religion and Spirituality Books for Youth: 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- "SLJ Best Books 2013 Fiction". November 21, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- Kellogg, Carolyn (April 11, 2014). "Jacket Copy: The winners of the Los Angeles Times Book Prizes are ..." Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

External links

- Boxers and Saints - Macmillan Books

- Boxers and Saints - Gene Luen Yang official site