Boston Port Act

The Boston Port Act was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain[1] which became law on March 31, 1774, and took effect on June 1, 1774.[2] It was one of five measures (variously called the Intolerable Acts, the Punitive Acts or the Coercive Acts) that were enacted during the spring of 1774 to punish Boston for the Boston Tea Party.[3]

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Long title | An act to discontinue, in such manner, and for such time as are therein mentioned, the landing and discharging, shipping of goods, wares, and merchandise, at the town, and within the harbour, of Boston, in the province of Massachusetts Bay, in North America. |

|---|---|

| Citation | 14 Geo. III. c. 19 |

| Territorial extent | Province of Massachusetts Bay |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | March 20, 1774 |

| Commencement | June 1, 1774 |

| Other legislation | |

| Relates to | Intolerable Acts |

Status: Repealed | |

Background

The Act was a response to the Boston Tea Party. King George III's speech of March 7, 1774 charged the colonists with attempting to injure British commerce and subvert the constitution. On March 18, Lord North brought in the Port Bill, which outlawed the use of the Port of Boston (by setting up a barricade/blockade) for "landing and discharging, loading or shipping, of goods, wares, and merchandise" until restitution was made to the King's treasury (for customs duty lost) and to the East India Company for damages suffered. In other words, it closed Boston Port to all ships, no matter what business the ship had. It also provided that Massachusetts Colony's seat of government should be moved to Salem and Marblehead made a port of entry. The Act was to take effect on June 1.[4]

Passage

Even some of the strongest allies of America in Parliament at first approved the Act as moderate and reasonable and argued that the town could end the punishment at any time by paying for the merchandise destroyed in the riot and allowing law and order to have their course. However, the Whig opposition soon collected itself, and the bill was fought in its various stages by Edmund Burke, Isaac Barré, Thomas Pownall and others. In spite of them, the Act became a law on March 31, without a division in the Commons and by a unanimous vote in the Lords.[4]

Aftermath

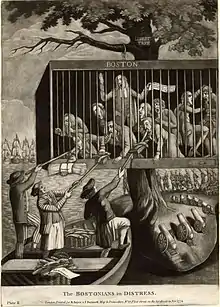

Royal Navy warships subsequently began patrols at the mouth of Boston Harbor to enforce the acts. The British Army also joined in enforcing the blockade, and Boston was filled with troops, Thomas Gage, commander-in-chief.[4] Colonists protested that the Port Act penalized thousands of residents and violated their rights as subjects of George III.[2] As the Port of Boston was a major source of supplies for the citizens of Massachusetts, sympathetic colonies as far away as South Carolina sent relief supplies to the settlers of Massachusetts Bay. So great was the response that the Boston leaders boasted that the town would become the chief grain port of America unless the act was not repealed.[4]

June 1 was widely observed as a day of fasting and prayer, bells being tolled, flags placed at half-mast, and houses draped in mourning.[5] That was the first step in the unification of the thirteen colonies since they now had a cause for which to work together.

The First Continental Congress was convened in Philadelphia on September 5, 1774 to co-ordinate a colonial response to the Port Act and the other Coercive Acts.[6]

References

- 14 Geo. III. c. 19

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory, ed. (2007). "Boston Port Act (1774)". Encyclopedia of the Age of Political Revolutions and New thoughts, 1760-1815. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 84–85. ISBN 9780313049514.

- Ciment, James (2016). Colonial America: An Encyclopedia of Social, Political, Cultural, and Economic History. Routledge. p. 684. ISBN 9781317474166.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- Ciment (2016), p. 684.

Further reading

- Frothingham, Richard (1873). The Rise of the Republic of the United States. Boston: Little, Brown and Co.

- Halsey, R. T. H. (1904). The Boston Port Bill. Grolier Club.

External links

- Full text of the Boston Port Act

- Observations on the act of Parliament commonly called the Boston port-bill : with thoughts on civil society and standing armies Boston, N.E.; London: Re-printed for Edward and Charles Dilly