Board puzzles with algebra of binary variables

Board puzzles with algebra of binary variables ask players to locate the hidden objects based on a set of clue cells and their neighbors marked as variables (unknowns). A variable with value of 1 corresponds to a cell with an object. Contrary, a variable with value of 0 corresponds to an empty cell—no hidden object.

Overview

These puzzles are based on algebra with binary variables taking a pair of values, for example, (no, yes), (false, true), (not exists, exists), (0, 1). It invites the player quickly establish some equations, and inequalities for the solution. The partitioning can be used to reduce the complexity of the problem. Moreover, if the puzzle is prepared in a way that there exists a unique solution only, this fact can be used to eliminate some variables without calculation.

The problem can be modeled as binary integer linear programming which is a special case of integer linear programming.[1]

History

Minesweeper, along with its variants, is the most notable example of this type of puzzle.

Algebra with binary variables

Below the letters in the mathematical statements are used as variables where each can take the value either 0 or 1 only. A simple example of an equation with binary variables is given below:

- a + b = 0

Here there are two variables a and b but one equation. The solution is constrained by the fact that a and b can take only values 0 or 1. There is only one solution here, both a = 0, and b = 0. Another simple example is given below:

- a + b = 2

The solution is straightforward: a and b must be 1 to make a + b equal to 2.

Another interesting case is shown below:

- a + b + c = 2

- a + b ≤ 1

Here, the first statement is an equation and the second statement is an inequality indicating the three possible cases:

- a = 1 and b = 0,

- a = 0 and b = 1, and

- a = 0 and b = 0,

The last case causes a contradiction on c by forcing c = 2, which is not possible. Therefore, either first or second case is correct. This leads to the fact that c must be 1.

The modification of a large equation into smaller form is not difficult. However, an equation set with binary variables cannot be always solved by applying linear algebra. The following is an example for applying the subtraction of two equations:

- a + b + c + d = 3

- c + d = 1

The first statement has four variables whereas the second statement has only two variables. The latter one means that the sum of c and d is 1. Using this fact on the first statement, the equations above can be reduced to

- a + b = 2

- c + d = 1

The algebra on a board

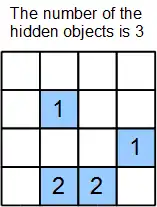

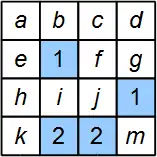

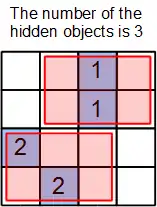

A game based on the algebra with binary variables can be visualized in many different ways. One generic way is to represent the right side of an equation as a clue in a cell (clue cell), and the neighbors of a clue cell as variables. A simple case is shown in Figure 1. The neighbors can be assumed to be the up/down, left/right, and corner cells that are sharing an edge or a corner. The white cells may contain a hidden object or nothing. In other words, they are the binary variables. They take place on the left side of the equations. Each clue cell, a cell with blue background in Figure 1, contains a positive number corresponding to the number of its neighbors that have hidden objects. The total number of the objects on the board can be given as an additional clue. The same board with variables marked is shown in Figure 2.

The reduction into a set of equations with binary variables

The main equation is written by using the total number of the hidden objects given. From the first figure this corresponds to the following equation

- a + b + c + d + e + f + g + h + i + j + k + m = 3

The other equations are composed one by one for each clue cells:

- a + b + c + e + f + h + i + j = 1

- f + g + j + m = 1

- h + i + j + k = 2

- i + j + m = 2

Although there are several ways to solve the equations above, the following explicit way can be applied:

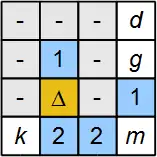

- It is known from the equation set that i + j + m = 2. However, since j and m are neighbors of a cell with number 1, the following is true: j + m ≤ 1. This means that the variable i must be 1.

- Since i = 1 and the variable i is the neighbor to the clue cell with number 1, the variables a, b, c, e, f, h, and j must be zero. The same result can be obtained by replacing i = 1 into the second equation as follows: a + b + c + e + f + h + j = 0. This is equivalent to a = 0, b = 0, c = 0, e = 0, f = 0, h = 0, j = 0.

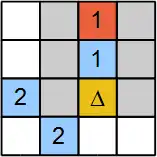

- Figure 3 is obtained after Step 1 and Step 2. The grayed cells with '–' are the variables with value 0. The cell with the symbol Δ corresponds to the variable with value 1. The variable k is the only neighbor of the left most clue cell with value 2. This clue cell has one neighbor with an object and only one remaining cell with variable k. Therefore, k must be 1.

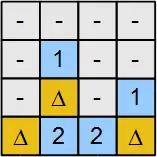

- Similarly, the variable m must be 1 too because it is the only remaining variable neighbor to the right most clue cell with value 2.

- Since k = 1, m = 1 and i = 1, we complete the marking of three hidden objects therefore d = 0, and g = 0. The final solution is given in Figure 4.

Figure 2: Binary variables are marked |

Figure 3: The example solved partially |

Figure 4: The example solved |

Use of uniqueness

In the example above (Figure 2), the variables a, b, c, and e are the neighbors of the clue cell 1 and they are not neighbors of any other cell. It is obvious that the followings are possible solutions:

- a = 1, b = 0, c = 0, e = 0

- a = 0, b = 1, c = 0, e = 0

- a = 0, b = 0, c = 1, e = 0

- a = 0, b = 0, c = 0, e = 1

However, if the puzzle is prepared so that we should have one only one (unique) solution, we can set that all these variables a, b, c, and e must be 0. Otherwise there become more than one solutions.

Use of partitioning

Some puzzle configurations may allow the player to use partitioning[2] for complexity reduction. An example is given in Figure 5. Each partition corresponds to a number of the objects hidden. The sum of the hidden objects in the partitions must be equal to the total number of objects hidden on the board. One possible way to determine a partitioning is to choose the lead clue cells which have no common neighbors. The cells outside of the red transparent zones in Figure 5 must be empty. In other words, there are no hidden objects in the all-white cells. Since there must be a hidden object within the upper partition zone, the third row from top shouldn't contain a hidden object. This leads to the fact that the two variable cells on the bottom row around the clue cell must have hidden objects. The rest of the solution is straightforward.

Use of try-and-check method

At some cases, the player can set a variable cell as 1 and check if any inconsistency occurs. The example in Figure 6 shows an inconsistency check. The cell marked with an hidden object Δ is under the test. Its marking leads to the set all the variables (grayed cells) to be 0. This follows the inconsistency. The clue cell marked red with value 1 does not have any remaining neighbor that can include a hidden object. Therefore, the cell under the test must not include a hidden object. In algebraic form we have two equations:

- a + b + c + d = 1

- a + b + c + d + e + f + g = 1

Here a, b, c, and d correspond to the top four grayed cells in Figure 6. The cell with Δ is represented by the variable f, and the other two grayed cells are marked as e and g. If we set f = 1, then a = 0, b = 0, c = 0, d = 0, e = 0, g = 0. The first equation above will have the left hand side equal to 0 while the right hand side has 1. A contradiction.

Try-and-check may need to be applied consequently in more than one step on some puzzles in order to reach a conclusion. This is equivalent to binary search algorithm[3] to eliminate possible paths which lead to inconsistency.

Complexity

Because of binary variables, the equation set for the solution does not possess linearity property. In other words, the rank of the equation matrix may not always address the right complexity.

The complexity of this class of puzzles can be adjusted in several ways. One of the simplest method is to set a ratio of the number of the clue cells to the total number of the cells on the board. However, this may result a largely varying complexity range for a fixed ratio. Another method is to reduce clue cells based on some problem solving strategies step by step. The complex strategies may be enabled for high complexity levels such as subtracting an equation with another one, or the higher depth of try-and-check steps. When the board size increases, the range of the problem cases increases. The ratio of the number of hidden objects to the total number of cells affects the complexity of the puzzle too.

Notes

- Schrijver 1986

- Halmos 1960

- Drozdek 2000

References

- Paul Halmos, Naive set theory. Princeton, NJ: D. Van Nostrand Company, 1960. Reprinted by Springer-Verlag, New York, 1974. ISBN 0-387-90092-6 (Springer-Verlag edition).

- Alexander Schrijver, Theory of Linear and Integer Programming. John Wiley & Sons, 1986. Reprinted in 1999. ISBN 0-471-98232-6.

- Adam Drozdek, Data Structures and Algorithms in C++, Brooks/Cole, second edition, 2000. ISBN 0-534-37597-9.