Blonde Ice

Blonde Ice is a crime film noir released on July 24, 1948, directed by Jack Bernhard with music by Irving Gertz.[1] The film was originally released as a B movie. This means the film is a low budget commercial film along with a feature movie. The film stars Leslie Brooks as Claire Cummings Hanneman, Robert Paige as Les Burns, and Michael Whalen as Stanley Mason. It is based on the 1938 novel Once Too Often by Elwyn Whitman Chambers.[2] Claire is a society reporter and serial killer who is willing to go to extremes if it means publishing a story. She manages to keep herself in the headlines by marrying and seducing a series of wealthy men. However, all of these men die under certain mysterious circumstances. In order to protect her reputation, as well as deflect suspicion from herself, Claire frames her former boyfriend, the sportswriter Les Burns.

| Blonde Ice | |

|---|---|

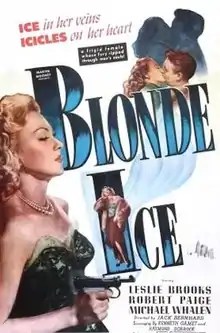

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jack Bernhard |

| Produced by | Martin Mooney |

| Screenplay by | Kenneth Gamet |

| Based on | Once Too Often (1938 novel) by Whitman Chambers |

| Starring | Leslie Brooks Robert Paige Michael Whalen |

| Music by | Irving Gertz |

| Cinematography | George Robinson |

| Edited by | W.L. Bagier Jason H. Bernie |

Production company | Martin Mooney Productions |

| Distributed by | Film Classics |

Release date |

|

Running time | 74 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Plot

Claire Cummings, a society columnist for a San Francisco paper, is about to marry Carl Henneman in his opulent mansion. A small group of men - all Claire's old co-workers from the newspaper - comment about Claire being late to her own wedding. At least two of the men attending - Les Burns and Al Herrick - are ex-lovers of Claire's. Claire appears at the top of the stairs as the wedding march begins, making her way down the stairs and into the ceremony. As the ceremony takes place, Les leaves to go stand on the veranda, and Claire watches him, instead of focusing on her wedding. Immediately following the ceremony Claire slips out to join Les and tells him she still loves him and will continue to see him, despite now being married. She kisses him, which her new husband sees. When Claire re-enters the reception, Carl confronts his new bride, who tells him that Les is like her brother, and the kiss was platonic. Carl believes her.

While on their honeymoon in Los Angeles, Claire and Carl are at the racetrack, arguing about Claire's reckless betting on random horses. Claire thinks it doesn't matter, since Carl's wealthy, but Carl wants her to be more frugal. The couple return to their hotel where Claire writes a love letter to Les. When Carl enters the room she hides the letter under another letter but Carl quickly discovers it and tells her he's going to divorce her. At first she barely reacts, telling Carl that California's a state with community property laws which entitle a spouse to half of a couple's combined holdings. But Carl says he's taking the letter Claire had been writing to Les as proof of adultery so she won't receive any recompense. Carl leaves, heading back to San Francisco to begin divorce proceedings.

Claire hatches a plan; she heads to an airfield where she finds a pilot, Blackie Talon, who is willing to fly her immediately to San Francisco and back. She pays him extra to buy his silence.

The next morning Claire phones Les and tells him Carl has flown to New York on business and she is planning to return to San Francisco where she'll spend the rest of her honeymoon time with him. She asks Les to arrange a flight for her and to pick her up at the airport. After the pick-up Claire asks him to drive to Carl's mansion so she can get some clothes.

Upon arriving, Les makes a gruesome discovery - Carl's dead body in an easy chair, a gun on the carpet. It looks like suicide. Les phones the police, although Claire seems unfazed. The two are questioned at the police station. The police think Carl's death could not have been suicide as there are no fingerprints on the gun, nor powder burns on his hands or clothes. They suspect Claire, but she has a strong alibi; she states that she was in Los Angeles at the time of the murder and has the plane ticket and Les to back her up.

Les and Claire rekindle their romance, as if her whirlwind marriage and the subsequent death of Carl Henneman had never taken place. One night while out to dinner Claire spots Stanley Mason, an attorney who is currently running for congress. She asks Les about him and brings up the idea of his handling Carl's estate. She arranges an introduction and tells Mason that she could use a good lawyer to handle her late husband's estate. He decides to help her and in no time the pair become lovers.

Les finds himself once again losing Claire to another man. At the same time the police are coming down hard on him, as he is their prime suspect. Les realises there are too many holes in the scenario of Carl's "suicide" and confronts Claire, telling her, "You're not a normal woman. You're not warm. You're cold, like ice. Yeah, like ice - blonde ice."[3]

After Claire has thrown Les out Blackie arrives, demanding 50,000 dollars for his silence. He takes her necklace as a first installment. The next evening, Claire and Stanley are joined at dinner by psychologist Dr. Kippinger, who openly comments on the manipulative aspect of her nature.

With the police having closed Carl's murder case, due to insufficient evidence, Claire is able to relax somewhat. But then Blackie phones, demanding money. Claire drives to meet him but shoots him as he gets out of the car.

At the victory party where Stanley celebrates his election victory, he also announces that he is going to marry Claire. Les leaves in consternation. He is home alone, having a drink, when Claire walks in and tells him she really loves him. He calls her poison. She puts her arms around him and at that moment Stanley walks in. He has come to break off their engagement and nothing Claire can say will dissuade him.

Claire murders Stanley with a knife and when Les walks in, he picks up the knife, making it easy for her to pin the murder on him. The police come and arrest Les but Dr. Kippinger is certain the real murderer is Claire. He confronts her at her newspaper office and discovers that she has written a confession about the murders of Carl, Blackie and Stanley. Claire tries to shoot Dr. Kippinger but misses and as she and Al grapple for the gun she shoots and kills herself.

In the final scene a bunch of people come into the office and look down at the body. Les leaves last, shutting the door behind him.

Cast

- Robert Paige as Les Burns

- Leslie Brooks as Claire Cummings Hanneman

- Russ Vincent as Blackie Talon, the Pilot

- Michael Whalen as Stanley Mason, Attorney

- James Griffith as Al Herrick

- Emory Parnell as Police Capt. Bill Murdock

- Walter Sande as Hack Doyle

- John Holland as Carl Hanneman

- Mildred Coles as June Taylor

- Selmer Jackson as District Attorney Ed Chalmers

- David Leonard as Dr. Geoffrey Kippinger

Crew

- Director: Jack Bernhard

- Producer: Martin Mooney

- Associate Producer: Robert E. Callahan

- Music Composed and Arranged by Irving Gertz

- Special Effects: Ray Mercer, a.s.c

- Assistant Director: Frank Fox

- Make-up Artist: Teo Larsen

- Set Director: Joe Kirsch

- Sound Engineer: Ferol Redo

- Props Master: George Bahr

- Production Manager: George Moskov

- Assistant to Producer: William Stirling

- Director of Photography: George Robinson

- Set Designer: George Van Marter

- Film Editors: Jason H. Bernie and Douglas W. Bagier

Film noir

The term film noir first came to vision by the French film critic, Nino Frank in 1946. The dark themes of the films corresponded with the popular looks of American crime/detective films which were released post World War II. The Maltese Falcon, Laura, and The Woman in the Window are popular films released during this time that fit well with common film noir themes. The introduction of film noirs provided a more serious counterpart to musicals and comedies which were popular during the 1940s in Hollywood.

A misconception with film noir is that it's a genre, however, it falls under the category of mood or style. It is a reference to the films produced post World War II. This style of film lasted for around ten years. When movies began to be rapidly produced in color, the style died out. However, the popularity of television greatly contributed to the fall of film noir. Film noirs have inspired current Hollywood cult classics like L.A. Confidential, Cast a Deadly Spell, and Fight Club. Generally, these are classified as neo-noirs.

A film with a detective and a voice-over can usually be marked as a film noir. Dark and oppressive lighting, a script based on an "American pulp fiction." And for fun, add in a bleak view of humanity. Sure, there are more indicators of a film noir, such as an obsession with the past or heavy smoking and drinking, but the real elements of a film noir comes from the frame composition and cinematic focus of a film. Since gritty elements like sex and violence were restricted during the filming of Blonde Ice, dramatic placement of characters and creative camera angles had to be used in order to convey the kind of tension one would receive from a movie that was not allowed to portray an inordinate amount of violence and sex.

There is a scene were we see Stanley Mason in his office after his engagement to Claire. This scene draws a lot of importance as Claire, struggles with Herrick and with a handgun. She ends up getting shot in the struggle.

The deep focus shot provides the building suspense to viewers. The deep focus shots and asymmetrical balance to the frame in this instance is so important to the film makers so they could adequately convey the right amount of tension in the a time period where violence was restricted.

Lighting is probably one of the most defining features of a film noir. High contrast, no fill light, and extremely long shadows. The darker the better. We see the use of extreme high and low angles as well as "choker" close up shots, so the film is able to convey intensity.

A great example that makes this film a film noir is the poetic language used in the script. Les, our male lead says, "I once said I couldn’t figure you out. I can now. You’re not a normal woman. You’re not warm. You’re cold like ice. Yeah, like ice. Blonde ice." A quick firing conversation filled with poetic turn arounds, marks the film as a definite film noir.[5]

Critical response

Film critic Dennis Schwartz called the film a "minor film noir." He wrote, "A minor film noir about a cold-hearted femme fatale who is capable of not only deceit but of murder. It's a precursor to the more hardboiled neo-noir films of today. Jack Bernhard directs a film that is based on a Whitney Chambers story, and allows the storyline to remain an oddity because of how ruthlessly cold and insane the femme fatale character played by Leslie Brooks is presented."[6]

Critic Gary Johnson discussed the production and the storyline in his review, "The acting is merely adequate and the direction is severely hampered by the low budget (although director Jack Bernhard and cameraman George Robinson do manage a few surprising camera angles). But the screenplay is a deliciously nasty and audacious exposé on the twisted psyche of a truly lethal femme fatale. Claire Cummings is a gold digger with no conscience whatsoever. She's out for herself and if anyone gets in the way, well ... she packs a revolver and a sharp knife. Claire Cummings is one of the most deadly femme fatales in the history of film noir, easily fitting alongside such other brutal dames as Phyllis Dietrichson from Double Indemnity, Kathie Moffat from Out of the Past, Annie Laurie Starr from Gun Crazy, and Vera from Edgar G. Ulmer's own Detour.[7]

When the movie was released, there was confusion about who the screenwriter was. Some sources state that much acclaimed B movie director Edgar G. Ulmer was the uncredited original screenwriter of Blonde Ice. However, this theory has been disproven. In a conversation with Peter Bogdanovich, a film director and writer, Ulmer claimed that after the huge box office success of Double Indemnity (1944) he wrote a rip-off script with the working title Single Indemnity for film producer Sigmund Neufeld. He erroneously believed that Neufeld's film was released under the title Blonde Ice.[8] However, Blonde Ice was neither produced by Neufeld nor does its plot resemble that of Double Indemnity. Therefore, there is no connection between Ulmer and the screenplay of Blonde Ice. It is believed the film Ulmer was actually referring to is Apology for Murder (1945)

Restoration

Blonde Ice was in originality directed by Jack Bernhard, a British-American director responsible for films such as Decoy (1946), Unknown Island (1948), and The Second Face (1950).[9] The film, which in its own time was glanced over by most movie-goers due to its status as a B Movie, had been considered lost until its reappearance in 2003, when it was restored and re-released to the public by VCI entertainment.[10] Blonde Ice was originally created through the production company Film Classics, yet was re-discovered through private collectors and restored by historian Jay Fenton.[11] The restored DVD release of Blonde Ice includes an interview with Jay Fenton himself, where he describes his role as a film collector. It was illegal to privately own a print copy of a film due to the imposing threat of pirating and re-selling of the movies, though many people such as Jay Fenton saved works despite the law, providing the present day with many previously lost works such as Blonde Ice.

Novel

Much like the film, most copies of the novel have been lost, yet few still remain in circulation. "Once Too Often" was released in 1938, yet is often referenced as a similar novel published in the same year, "Murder Lady", which was widely released by Chambers in the United Kingdom.[12] The title of this work is now shared with that of a novel written by author Dorothy Simpson in 2016.[13] The two works have no relation to one another, yet the popularity of Simpson's novel decreased the ease of locating the work written by Chambers. Many websites that are known for selling antique titles no longer carry Chambers' "Once Too Often", and few copies exist in public and educational libraries. Private collectors make up the majority of ownership with this title, making it difficult for historians to track them all down or know the true total of books left in circulation.

References

- Blonde Ice (1948), 2018-10-21, retrieved 2019-03-01

- SFE Chambers, Whitman, 2018-08-11, retrieved 2019-02-28

- Bernhard, Jack; Mooney, Martin. "Blonde Ice".

- Blonde Ice (1948), retrieved 2019-02-27

- Dirks, Tim. "Film Noir". AMC Film Site. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- Schwartz, Dennis Archived 2017-12-12 at the Wayback Machine. Ozus' World Movie Reviews, film review, October 13, 2002. Accessed: July 23, 2013.

- Johnson, Gary. Images Journal, film review, 2003. Accessed: July 23, 2013.

- Bogdanovich, Peter. Who The Devil Made It: Conversations with Legendary Film Directors, 1997. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-679-44706-7.

- Jack Bernhard, 2014-02-28

- Film-Noir-of-the-Week, 2010-08-22, retrieved 2019-02-28

- Jay Fenton On "Blonde Ice", retrieved 2019-02-28

- Chambers, Whitman, 2008-06-09, retrieved 2019-02-28

- Simon & Schuster, retrieved 2019-03-01

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Blonde Ice. |

- Blonde Ice complete film on YouTube

- Blonde Ice at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Blonde Ice at IMDb

- Blonde Ice at AllMovie

- Blonde Ice at the TCM Movie Database

- Blonde Ice at Rotten Tomatoes

- Blonde Ice is available for free download at the Internet Archive