Biomimetic architecture

Biomimetic architecture is a branch of the new science of biomimicry defined and popularized by Janine Benyus in her 1997 book (Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature). Biomimicry (bios - life and mimesis - imitate) refers to innovations inspired by nature as one which studies nature and then imitates or takes inspiration from its designs and processes to solve human problems.[1] The book suggests looking at nature as a ‘‘Model, Measure, and Mentor”, suggesting that the main aim of biomimicry is sustainability.

Living beings have adapted to a constantly changing environment during evolution through mutation, recombination, and selection.[2] The core idea of the biomimetic philosophy is that nature’s inhabitants including animals, plants, and microbes have the most experience in solving problems and have already found the most appropriate ways to last on planet Earth. Similarly, biomimetic architecture seeks solutions for building sustainability present in nature, not only by replicating their natural forms, but also by understanding the rules governing those forms.

The 21st century has seen a ubiquitous waste of energy due to inefficient building designs,[3] in addition to the over-utilization of energy during the operational phase of its life cycle. In parallel, recent advancements in fabrication techniques, computational imaging, and simulation tools have opened up new possibilities to mimic nature across different architectural scales.[2] As a result, there has been a rapid growth in devising innovative design approaches and solutions to counter energy problems. Biomimetic architecture is one of these multi-disciplinary approaches to sustainable design that follows a set of principles rather than stylistic codes, going beyond using nature as inspiration for the aesthetic components of built form, but instead seeking to use nature to solve problems of the building's functioning and saving energy.

History

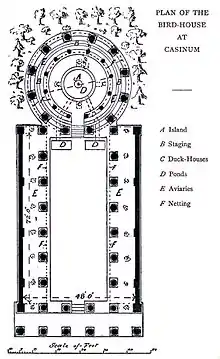

Architecture has long drawn from nature as a source of inspiration. Biomorphism, or the incorporation of natural existing elements as inspiration in design, originated possibly with the beginning of man-made environments and remains present today. The ancient Greeks and Romans incorporated natural motifs into design such as the tree-inspired columns. Late Antique and Byzantine arabesque tendrils are stylized versions of the acanthus plant.[4] Varro's Aviary at Casinum from 64 BC reconstructed a world in miniature.[5][6] A pond surrounded a domed structure at one end that held a variety of birds. A stone colonnaded portico had intermediate columns of living trees.

The Sagrada Família church by Antoni Gaudi begun in 1882 is a well-known example of using nature's functional forms to answer a structural problem. He used columns that modeled the branching canopies of trees to solve statics problems in supporting the vault.[7]

Organic architecture uses nature-inspired geometrical forms in design and seeks to reconnect the human with his or her surroundings. Kendrick Bangs Kellogg, a practicing organic architect, believes that “above all, organic architecture should constantly remind us not to take Mother Nature for granted – work with her and allow her to guide your life. Inhibit her, and humanity will be the loser.”[8] This falls in line with another guiding principle, which is that form should follow flow and not work against the dynamic forces of nature.[9] Architect Daniel Liebermann's commentary on organic architecture as a movement highlights the role of nature in building: “…a truer understanding of how we see, with our mind and eye, is the foundation of everything organic. Man’s eye and brain evolved over aeons of time, most of which were within the vast untrammeled and unpaved landscape of our Edenic biosphere! We must go to Nature for our models now, that is clear!”[8] Organic architects use man-made solutions with nature-inspired aesthetics to bring about an awareness of the natural environment rather than relying on nature's solutions to answer man's problems.

Metabolist architecture, a movement present in Japan post-WWII, stressed the idea of endless change in the biological world. Metabolists promoted flexible architecture and dynamic cities that could meet the needs of a changing urban environment.[10] The city is likened to a human body in that its individual components are created and become obsolete, but the entity as a whole continues to develop. Like the individual cells of a human body that grow and die although human body continues to live, the city, too, is in a continuous cycle of growth and change.[11] The methodology of Metabolists views nature as a metaphor for the man-made. Kisho Kurokawa's Helix City is modeled after DNA, but uses it as a structural metaphor rather than for its underlying qualities of its purpose of genetic coding.

Other historic attempts have been made, which are not directly related to the built environment. Some of these earliest successful attempts at mimicking nature include the electric battery, mimicking the living torpedo, by Alessandro Volta which dates back to the 1800s, as well as the first successful airplane built by Otto Lilienthal after 1889, looking at birds as biological role models.[2]

Characteristics

The term Biomimetic architecture refers to the study and application of construction principles which are found in natural environments and species, and are translated into the design of sustainable solutions for architecture.[2] Biomimetic architecture uses nature as a model, measure and mentor for providing architectural solutions across scales, which are inspired by natural organisms that have solved similar problems in nature. Using nature as a measure refers to using an ecological standard of measuring sustainability, and efficiency of man-made innovations, while the term mentor refers to learning from natural principles and using biology as an inspirational source.[1]

Biomorphic architecture, also referred to as Bio-decoration,[2] on the other hand, refers to the use of formal and geometric elements found in nature, as a source of inspiration for aesthetic properties in designed architecture, and may not necessarily have non-physical, or economic functions. A historic example of biomorphic architecture dates back to Egyptian, Greek and Roman cultures, using tree and plant forms in the ornamentation of structural columns.[12]

Within Biomimetic architecture, two basic procedures can be identified, namely, the bottom-up approach (biology push) and top-down approach (technology pull).[13] The boundary between these is blurry with the possibility of transitioning between the two approaches depending on individual cases. Biomimetic architecture is typically carried out in highly interdisciplinary teams in which biologists and other natural scientists work in collaboration with engineers, scientists, and designers. In the bottom-up approach, the starting point is a new result from basic biological research promising for biomimetic implementation. For example, developing a biomimetic material system after the quantitative analysis of the mechanical, physical, and chemical properties of a biological system. In the top-down approach, biomimetic innovations are sought for already existing developments that have been successfully established on the market. The cooperation focuses on the improvement or further development of an existing product.

Mimicking nature requires understanding the differences between biological and technical systems. Their evolution is dissimilar: biological systems have been evolving for millions of years, whereas the technical systems have been developing for only a few hundred years. Biological systems evolved based on their genetic codes governed by natural selection, while technical systems developed based on human design for performing functions. In general, functions in technical systems aim to develop a system as a result of design, while in biological systems, functions can occasionally be an unsystematic genetic evolutionary change that leads to a particular function that is not prearranged. Their differences are wide: technical systems function within extensive environments, while biological systems work within restricted living constraints.[14]

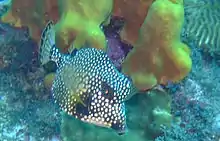

Architectural innovations that are responsive to architecture do not have to resemble a plant or an animal. Where form is intrinsic to an organism's function, then a building modeled on a life form's processes may end up looking like the organism too. Architecture can emulate natural forms, functions and processes. Though a contemporary concept in a technological age, biomimicry does not entail the incorporation of complex technology in architecture. In response to prior architectural movements biomimetic architecture strives to move towards radical increases in resource efficiency, work in a closed loop model rather than linear (work in a closed cycle that does not need a constant intake of resources to function), and rely on solar energy instead of fossil fuels. The design approach can either work from design to nature or from nature to design. Design to nature means identifying a design problem and finding a parallel problem in nature for a solution. An example of this is the DaimlerChrysler bionic car that looked to the boxfish to build an aerodynamic body.[15] The nature to design method is a solution-driven biologically inspired design. Designers start with a specific biological solution in mind and apply it to design. An example of this is Sto's Lotusan paint, which is self-cleaning, an idea presented by the lotus flower, which emerges clean from swampy waters.[16]

Three Levels of Mimicry

Biomimicry can work on three levels: the organism, its behaviors, and the ecosystem. Buildings on the organism level mimic a specific organism. Working on this level alone without mimicking how the organism participates in a larger context may not be sufficient to produce a building that integrates well with its environment because an organism always functions and responds to a larger context. On a behavior level, buildings mimic how an organism behaves or relates to its larger context. On the level of the ecosystem, a building mimics the natural process and cycle of the greater environment. Ecosystem principles follow that ecosystems (1) are dependent on contemporary sunlight; (2) optimize the system rather than its components; (3) are attuned to and dependent on local conditions; (4) are diverse in components, relationships and information; (5) create conditions favorable to sustained life; and (6) adapt and evolve at different levels and at different rates.[17] Essentially, this means that a number of components and processes make up an ecosystem and they must work with each other rather than against in order for the ecosystem to run smoothly. For architectural design to mimic nature on the ecosystem level it should follow these six principles.

Examples of biomimicry in architecture

Organism Level

On the organism level, the architecture looks to the organism itself, applying its form and/or functions to a building.

.JPG.webp)

Norman Foster’s Gherkin Tower (2003) has a hexagonal skin inspired by the Venus Flower Basket Sponge. This sponge sits in an underwater environment with strong water currents and its lattice-like exoskeleton and round shape help disperse those stresses on the organism.[18]

The Eden Project (2001) in Cornwall, England is a series of artificial biomes with domes modeled after soap bubbles and pollen grains. Grimshaw Architects looked to nature to build an effective spherical shape. The resulting geodesic hexagonal bubbles inflated with air were constructed of Ethylene Tetrafluoroethylene (ETFE), a material that is both light and strong.[19] The final superstructure weighs less than the air it contains.

Behavior Level

On the behavior level, the building mimics how the organism interacts with its environment to build a structure that can also fit in without resistance in its surrounding environment.

The Eastgate Centre designed by architect Mick Pearce in conjunction with engineers at Arup Associates is a large office and shopping complex in Harare, Zimbabwe. To minimize potential costs of regulating the building's inner temperature Pearce looked to the self-cooling mounds of African termites. The building has no air-conditioning or heating but regulates its temperature with a passive cooling system inspired by the self-cooling mounds of African termites.[20] The structure, however, does not have to look like a termite mound to function like one and instead aesthetically draws from indigenous Zimbabwean masonry.

The Qatar Cacti Building designed by Bangkok-based Aesthetics Architects for the Minister of Municipal Affairs and Agriculture is a projected building that uses the cactus's relationship to its environment as a model for building in the desert. The functional processes silently at work are inspired by the way cacti sustain themselves in a dry, scorching climate. Sun shades on the windows open and close in response to heat, just as the cactus undergoes transpiration at night rather than during the day to retain water.[21] The project reaches out to the ecosystem level in its adjoining botanical dome whose wastewater management system follows processes that conserve water and has minimum waste outputs. Incorporating living organisms into the breakdown stage of the wastewater minimizes the amount of external energy resources needed to fulfill this task.[21] The dome would create a climate and air controlled space that can be used for the cultivation of a food source for employees.

Ecosystem Level

Building on the ecosystem level involves mimicking of how the environments many components work together and tends to be on the urban scale or a larger project with multiple elements rather than a solitary structure.

The Cardboard to Caviar Project founded by Graham Wiles in Wakefield, UK is a cyclical closed-loop system using waste as a nutrient.[22] The project pays restaurants for their cardboard, shreds it, and sells it to equestrian centers for horse bedding. Then the soiled bedding is bought and put into a composting system, which produces a lot of worms. The worms are fed to roe fish, which produce caviar, which is sold back to the restaurants. This idea of waste for one as a nutrient for another has the potential to be translated to whole cities.[19]

The Sahara Forest Project designed by the firm Exploration Architecture is a greenhouse that aims to rely on solar energy alone to operate as a zero waste system.[23] The project is on the ecosystem level because its many components work together in a cyclical system. After finding that the deserts used to be covered by forests, Exploration decided to intervene at the forest and desert boundaries to reverse desertification. The project mimics the Namibian desert beetle to combat climate change in an arid environment.[19] It draws upon the beetle's ability to self-regulate its body temperature by accumulating heat by day and to collect water droplets that form on its wings. The greenhouse structure uses saltwater to provide evaporative cooling and humidification. The evaporated air condenses to fresh water allowing the greenhouse to remain heated at night. This system produces more water than the interior plants need so the excess is spewed out for the surrounding plants to grow. Solar power plants work off of the idea that symbiotic relationships are important in nature, collecting sun while providing shade for plants to grow. The project is currently in its pilot phase.

Lavasa, India is a proposed 8000-acre city by HOK (Hellmuth, Obata, and Kassabaum) planned for a region of India subject to monsoon flooding.[24] The HOK team determined that the site's original ecosystem was a moist deciduous forest before it had become an arid landscape. In response to the season flooding, they designed the building foundations to store water like the former trees did. City rooftops mimic native the banyan fig leaf looking to its drip-tip system that allows water to run off while simultaneously cleaning its surface.[25] The strategy to move excess water through channels is borrowed from local harvester ants, which use multi-path channels to divert water away from their nests.

Criticisms

Biomimicry has been criticized for distancing man from nature by defining the two terms as separate and distinct from one another. The need to categorize human as distinct from nature upholds the traditional definition of nature, which is that it is those things or systems that come into existence independently of human intention. Joe Kaplinsky further argues that in basing itself on nature's design, biomimicry risks presuming the superiority of nature-given solutions over the manmade.[26] In idolizing nature's systems and devaluing human design, biomimetic structures cannot keep up with the man-made environment and its problems. He contends that evolution within humanity is culturally based in technological innovations rather than ecological evolution. However, architects and engineers do not base their designs strictly off of nature but only use parts of it as inspiration for architectural solutions. Since the final product is actually a merging of natural design with a human innovation, biomimicry can actually be read as bringing man and nature in harmony with one another.

See also

HOK (Hellmuth, Obata, and Kassabaum) Biomimicry

Further reading

- Benyus, Janine. Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature. New York: Perennial, 2002. ISBN 978-0060533229

- "Biomimicry 3.8 Institute", Biomimicry 3.8 Institute, http://biomimicry.net/.

- Pawlyn, Michael. Biomimicry in Architecture. London: RIBA Publishing, 2011. ISBN 978-1859463758

- Vincent, Julian. Biomimetic Patterns in Architectural Design. Architectural Design 79, no. 6 (2009): 74-81. doi:10.1002/ad.982

- Al-Obaidi, Karam M., et al. Biomimetic building skins: An adaptive approach. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 79 (2017): 1472-1491. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.05.028

References

- Benyus, Janine M. (1997). Biomimicry : innovation inspired by nature (1st ed.). New York: Morrow. ISBN 0-688-13691-5. OCLC 36103979.

- Knippers, Jan; Nickel, Klaus G.; Speck, Thomas, eds. (2016). Biomimetic Research for Architecture and Building Construction. Biologically-Inspired Systems. 8. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46374-2. ISBN 978-3-319-46372-8.

- Radwan, Gehan.A.N.; Osama, Nouran (2016). "Biomimicry, an Approach, for Energy Effecient Building Skin Design". Procedia Environmental Sciences. 34: 178–189. doi:10.1016/j.proenv.2016.04.017.

- Alois Riegl, “The Arabesque” from Problems of style: foundations for a history of ornament, translated by Evelyn Kain, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, 1992), 266-305.

- A. W. van Buren and R. M. Kennedy, “Varro’s Aviary at Casinum,” The Journal of Roman Studies 9 (1919): 63.

- Pawlyn, Michael. Biomimicry in architecture (Second ed.). Newcastle upon Tyne. ISBN 978-0-429-34677-4. OCLC 1112508488.

- George R. Collins, “Antonio Gaudi: Structure and Form,” Perspecta 8 (1963): 89.

- David Pearson, New Organic Architecture: the breaking wave (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2001), 10.

- David Pearson, New Organic Architecture: the breaking wave (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2001), 14.

- Raffaele Pernice, “Metabolism Reconsidered: Its Role in the Architectural Context of the World,” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 3, no. 2 (2004), 359.

- Kenzo Tange, “A Plan for Tokyo, 1960: Toward a Structural Reorganization,” in Architecture Culture 1943-1968: A Documentary Anthology, ed. Joan Ockman, 325-334 (New York: Rizzoli, 1993), 327.

- Aziz, Moheb Sabry; El sherif, Amr Y. (March 2016). "Biomimicry as an approach for bio-inspired structure with the aid of computation". Alexandria Engineering Journal. 55 (1): 707–714. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2015.10.015.

- Speck, Thomas; Speck, Olga (2019), Wegner, Lars H.; Lüttge, Ulrich (eds.), "Emergence in Biomimetic Materials Systems", Emergence and Modularity in Life Sciences, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 97–115, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-06128-9_5, ISBN 978-3-030-06127-2, retrieved 2020-11-16

- Al-Obaidi, Karam M.; Azzam Ismail, Muhammad; Hussein, Hazreena; Abdul Rahman, Abdul Malik (13 June 2017). "Biomimetic building skins: An adaptive approach". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 79: 1472–1491. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.05.028. ISSN 1364-0321.

- “The Mercedes-Benz bionic car: Streamlined and light, like a fish in water - economical and environmentally friendly thanks to the latest diesel technology,” Daimler, last modified June 7, 2005, .

- “StoColor Lotusan Lotus-Effect façade paint,” Sto Ltd., http://www.sto.co.uk/25779_EN-Facade_paints-StoColor_Lotusan.htm Archived 2013-06-08 at the Wayback Machine.

- Salma Ashraf El Ahmar, “Biomimicry as a Tool for Sustainable Architectural Design: Towards Morphogenetic Architecture” (master’s thesis, Alexandria University, 2011), 22.

- Ehsaan, “Lord Foster’s Natural Inspiration: The Gherkin Tower,” biomimetic architecture (blog), March 24, 2010, http://www.biomimetic-architecture.com/2010/lord-fosters-natural-inspiration-the-gherkin-tower/ Archived 2012-05-18 at the Wayback Machine.

- Michael Pawlyn, “Using nature’s genius in architecture” (2011, February), [video file] Retrieved from http://www.ted.com/talks/michael_pawlyn_using_nature_s_genius_in_architecture.html?embed=true.

- Jill Fehrenbacher, “Biomimetic Architecture: Green Building in Zimbabwe Modeled After Termite Mounds,” Inhabitat, last modified November 29, 2012, http://inhabitat.com/building-modelled-on-termites-eastgate-centre-in-zimbabwe/.

- Bridgette Meinhold, “Qatar Sprouts a Towering Cactus Skyscraper,” Inhabitat, last modified March 17, 2009, http://inhabitat.com/qatar-cactus-office-building/.

- Michael Pawlyn, “Biomimicry,” in Green Design: From Theory to Practice, edited by Ken Yeang and Arthur Spector, (London: Black Dog, 2011), 37.

- “Sahara Forest Project,” Sahara Forest Project, Inc., http://saharaforestproject.com.

- “Lavasa is India’s planned hill city,” Lavasa Corporation Ltd., http://www.lavasa.com.

- John Gendall, “Architecture That Imitates Life,” Harvard Magazine, last modified October 2009, http://harvardmagazine.com/2009/09/architecture-imitates-life.

- Joe Kaplinsky, “Biomimicry versus humanism,” Architectural Design 76, (2006), 68.