Betsy Perk

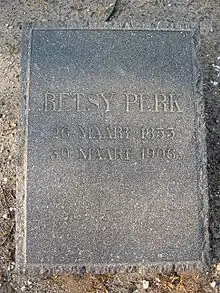

Christina Elizabeth (Betsy) Perk (Delft, March 26, 1833 - Nijmegen, March 30, 1906), was a Dutch author of novels and plays, and a pioneer of the Dutch women's movement,[1] who wrote under the pen names Philemon, Liesbeth van Altena, and Spirito. She is known as the founding member of the Algemeene Nederlandsche Vrouwenvereeniging Arbeid Adelt ("General Dutch Women's Association 'Labor Ennobles'") in 1871, the women's magazine Onze Roeping, and the weekly magazine for women Ons Streven in 1869, the latter publication being the country's first women's periodical. In later years, her influence and activism diminished due to poor health, and she mainly focused on writing historical novels. From 1880 to 1890, she lived in Belgium. She is buried at the cemetery Rustoord in Nijmegen.[2]

Betsy Perk | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Christina Elizabeth Perk March 26, 1833 Delft, Netherlands |

| Died | March 30, 1906 (aged 73) Nijmegen, Netherlands |

| Resting place | Rustoord Cemetery, Nijmegen |

| Pen name | Philemon, Liesbeth van Altena, Spirito |

| Occupation | author and a pioneer of the Dutch women's movement |

| Language | Dutch |

Early years and education

Perk grew up in a fairly wealthy and large family; her parents were Adrianus Perk and Lessina Elizabeth Visser. Her father, a merchant,[1] married three times and she was the third daughter of the second marriage. As a result, Perk had three brothers, three half-sisters and five half-brothers. She lived with her step-mother Theodora Veeren until 1876. One of her brothers was the father of the poet Jacques Perk.[3]

Career

From an early age she was interested in writing: she published some stories at age 19, and her first novel, Een kruis met rozen, was published in 1864.[4] Her father had been wealthy enough to send his sons for an academic education, but not his daughters, and in the 1860s her life was turned upside down: her fiancee broke off their engagement in 1866, and the next year her father died. Perk began publishing feminist articles, arguing that men and women should be valued equally, even if they had biological differences.[4]

She started Ons Streven ("Our Striving") in 1870, the country's first women's periodical, but left the magazine after the first edition since the publisher had placed two male editors on equal footing with her, and she feared the magazine would publish anti-emancipatory articles. In response she founded another magazine, Onze Roeping ("Our Calling"),[4] in which she suggested, among other things, that the work of unmarried and married women would promote the country's wellbeing.[2] In 1871, she established Arbeid Adelt, a women's association, for which Onze Roeping was the official journal, but quickly had a dispute with fellow associates: the organization sold poor women's needlework at bazaars, and unlike her colleagues Perk wished the names of the creators to be known: "her ambition was the recognition of labor as a worthy manner of life". A number of associates split off and founded a competing organization, and within her own organization she was soon pushed aside.[5]

Her last attempt to make her ideas known and simultaneously earn a living was in 1873, when she became a lecturer and went on tour with fellow-feminist Mina Kruseman, and while both women also published their ideas in the same magazines, the flamboyancy of Kruseman was compared in the press with Perk's modesty. When the tour ended, so did Perk's public work in feminism.[4] These years had asked a lot of her weak physique, and she withdrew to Valkenburg, where she toured the area on a donkey, and wrote an autobiography, Mijn ezeltje en ik. Een boek voor vriend en vijand ("My donkey and I: A book for friend and enemy", 1874), in which she settled her accounts with the world of literature and feminism. It was clear, though, that she may have been finished with the feminist movement, but she remained a firm proponent of emancipation.[4]

Later years

Perk had been a proponent of women's right to vote, and in 1894 joined the newly-founded Vereeniging voor Vrouwenkiesrecht. The women's movement seemed to have forgotten her: she was not invited to attend the large National Exhibition of Women's Labor in 1898. By then, she was back in the Netherlands, having moved to Arnhem in 1890 and to Nijmegen in 1903. She devoted her last years to art.[4]

Selected works

- Een kruis met rozen, 1864

- Wenken voor jonge dames ter bevordering van huiselijk geluk, 1868

- Elisabeth van Frankrijk, 1870

- Mijn ezeltje en ik. Een boek voor vriend en vijand, 1874

- De sterren liegen niet!, 1875

- Elisabeth de Jonkvrouw van 't kasteel te Valkenburg. Drama in voetmaat en vijf bedrijven uit 1355, 1878

- Valse schaamte, 1880

- Mejonkvrouw de Laval onder de keizers Alexander I en Nikolaas van Rusland, 1883

- De laatste der Bourgondiërs in Gent en Brugge 1477-1481, 1885

- Yline, prinses Daschkoff-Worenzoff. Uit de geschiedenis van Rusland, in de laatste helft der vorige eeuw, 1885

- Een recruut op Corsica onder luitenant Napoleon Bonaparte, 1887

- De wees van Averilo, 1888

- Kijkjes in België, 1888

- In het paleis der Bourgondiërs te Brussel, 1889

- Kapitein Flahol, 1890

- Een moederhart, 1896

- Jacques Perk, 1902

References

- Altena, Peter (1998). "Betsy Perk (1833-1906), schrijfster, feministe en tante". In van Wissing, P. W.; Kuys, J. A. E. (eds.). Biografisch woordenboek Gelderland: bekende en onbekende mannen en vrouwen uit de Gelderse geschiedenis. 2. Verloren. pp. 86–88. ISBN 9789065506245.

- "Betsy Perk en de eerste landelijke vrouwenvereniging - IsGeschiedenis". www.isgeschiedenis.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- Dieteren, Fia (12 November 2013). "Perk, Christina Elizabeth (1833-1906)". Biografisch Woordenboek van Nederland (in Dutch). 4. Den Haag. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- Paletschek, Sylvia (2005). Women's Emancipation Movements in the Nineteenth Century: A European Perspective. Stanford UP. p. 56. ISBN 9780804767071.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Betsy Perk. |