Bestiary

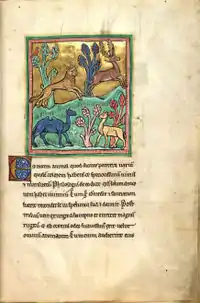

A bestiary (from bestiarum vocabulum) is a compendium of beasts. Originating in the ancient world, bestiaries were made popular in the Middle Ages in illustrated volumes that described various animals and even rocks. The natural history and illustration of each beast was usually accompanied by a moral lesson. This reflected the belief that the world itself was the Word of God and that every living thing had its own special meaning. For example, the pelican, which was believed to tear open its breast to bring its young to life with its own blood, was a living representation of Jesus. Thus the bestiary is also a reference to the symbolic language of animals in Western Christian art and literature.

History

The bestiary — the medieval book of beasts — was among the most popular illuminated texts in northern Europe during the Middle Ages (about 500–1500). Medieval Christians understood every element of the world as a manifestation of God, and bestiaries largely focused on each animal's religious meaning. The earliest bestiary in the form in which it was later popularized was an anonymous 2nd-century Greek volume called the Physiologus, which itself summarized ancient knowledge and wisdom about animals in the writings of classical authors such as Aristotle's Historia Animalium and various works by Herodotus, Pliny the Elder, Solinus, Aelian and other naturalists.

Following the Physiologus, Saint Isidore of Seville (Book XII of the Etymologiae) and Saint Ambrose expanded the religious message with reference to passages from the Bible and the Septuagint. They and other authors freely expanded or modified pre-existing models, constantly refining the moral content without interest or access to much more detail regarding the factual content. Nevertheless, the often fanciful accounts of these beasts were widely read and generally believed to be true. A few observations found in bestiaries, such as the migration of birds, were discounted by the natural philosophers of later centuries, only to be rediscovered in the modern scientific era.

Medieval bestiaries are remarkably similar in sequence of the animals of which they treat. Bestiaries were particularly popular in England and France around the 12th century and were mainly compilations of earlier texts. The Aberdeen Bestiary is one of the best known of over 50 manuscript bestiaries surviving today.

Bestiaries influenced early heraldry in the Middle Ages, giving ideas for charges and also for the artistic form. Bestiaries continue to give inspiration to coats of arms created in our time.[1]

Two illuminated Psalters, the Queen Mary Psalter (British Library Ms. Royal 2B, vii) and the Isabella Psalter (State Library, Munich), contain full Bestiary cycles. The bestiary in the Queen Mary Psalter is found in the "marginal" decorations that occupy about the bottom quarter of the page, and are unusually extensive and coherent in this work. In fact the bestiary has been expanded beyond the source in the Norman bestiary of Guillaume le Clerc to ninety animals. Some are placed in the text to make correspondences with the psalm they are illustrating.[2]

The Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci also made his own bestiary.[3]

A volucrary is a similar collection of the symbols of birds that is sometimes found in conjunction with bestiaries. The most widely known volucrary in the Renaissance was Johannes de Cuba's Gart der Gesundheit[4] which describes 122 birds and which was printed in 1485.[5]

Bestiary content

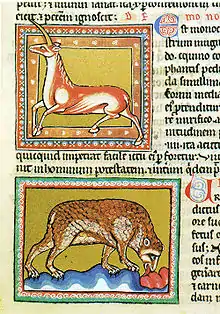

The contents of medieval bestiaries were often obtained and created from combining older textual sources and accounts of animals, such as the Physiologus.[6]

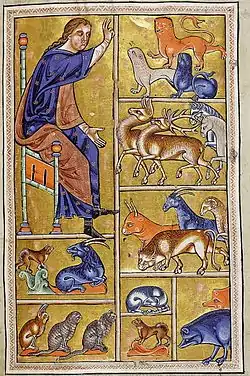

Medieval bestiaries contained detailed descriptions and illustrations of species native to Western Europe, exotic animals and what in modern times are considered to be imaginary animals. Descriptions of the animals included the physical characteristics associated with the creature, although these were often physiologically incorrect, along with the Christian morals that the animal represented. The description was then often accompanied by an artistic illustration of the animal as described in the bestiary.

Bestiaries were organized in different ways based upon the sources they drew upon.[7] The descriptions could be organized by animal groupings, such as terrestrial and marine creatures, or presented in an alphabetical manner. However, the texts gave no distinction between existing and imaginary animals. Descriptions of creatures such as dragons, unicorns, basilisk, griffin and caladrius were common in such works and found intermingled amongst accounts of bears, boars, deer, lions, and elephants.

This lack of separation has often been associated with the assumption that people during this time believed in what the modern period classifies as nonexistent or "imaginary creatures". However, this assumption is currently under debate, with various explanations being offered. Some scholars, such as Pamela Gravestock, have written on the theory that medieval people did not actually think such creatures existed but instead focused on the belief in the importance of the Christian morals these creatures represented, and that the importance of the moral did not change regardless if the animal existed or not. The historian of science David C. Lindberg pointed out that medieval bestiaries were rich in symbolism and allegory, so as to teach moral lessons and entertain, rather than to convey knowledge of the natural world.[8]

Modern bestiaries

In modern times, artists such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Saul Steinberg have produced their own bestiaries. Jorge Luis Borges wrote a contemporary bestiary of sorts, the Book of Imaginary Beings, which collects imaginary beasts from bestiaries and fiction. Nicholas Christopher wrote a literary novel called "The Bestiary" (Dial, 2007) that describes a lonely young man's efforts to track down the world's most complete bestiary. John Henry Fleming's Fearsome Creatures of Florida[9] (Pocol Press, 2009) borrows from the medieval bestiary tradition to impart moral lessons about the environment. Caspar Henderson's The Book of Barely Imagined Beings[10] (Granta 2012, Chicago University Press 2013), subtitled "A 21st Century Bestiary", explores how humans imagine animals in a time of rapid environmental change. In July 2014, Jonathan Scott wrote The Blessed Book of Beasts,[11] Eastern Christian Publications, featuring 101 animals from the various translations of the Bible, in keeping with the tradition of the bestiary found in the writings of the Saints, including Saint John Chrysostom.

The lists of monsters to be found in modern games such as roguelikes and RPGs (for example Monster Hunter and Pokémon) are often termed bestiaries.

See also

References

- "The Medieval Bestiary", by James Grout, part of the Encyclopædia Romana.

- McCulloch, Florence. (1962) Medieval Latin and French Bestiaries.

- Clark, Willene B. and Meradith T. McMunn. eds. (1989) Beasts and Birds of the Middle Ages. The Bestiary and its Legacy.

- Payne, Ann. (1990) "Mediaeval Beasts.

- George, Wilma and Brunsdon Yapp. (1991) The Naming of the Beasts: Natural History in the Medieval Bestiary.

- Benton, Janetta Rebold. (1992) The Medieval Menagerie: Animals in the Art of the Middle Ages.

- Lindberg, David C. (1992) The Beginnings of Western Science. The European Tradition in Philosophhical, Religious and Institutional Context, 600 B. C. to A. D. 1450

- Flores, Nona C. (1993) "The Mirror of Nature Distorted: The Medieval Artist's Dilemma in Depicting Animals".

- Hassig, Debra (1995) Medieval Bestiaries: Text, Image, Ideology.

- Gravestock, Pamela. (1999) "Did Imaginary Animals Exist?"

- Hassig, Debra, ed. (1999) The Mark of the Beast: The Medieval Bestiary in Art, Life, and Literature.

Notes

- Friar, Stephen, ed. (1987). A New Dictionary of Heraldry. London: Alphabooks/A&C Black. p. 342. ISBN 0-906670-44-6.

- The Queen Mary psalter: a study of affect and audience By Anne Rudloff Stanton, p44ff, Diane Publishing

- Evans, Oliver (Oct–Dec 1951). "Selections from the Bestiary of Leonardo da Vinci". The Journal of American Folklore. 64 (254): 393–396. doi:10.2307/537007. JSTOR 537007.

- de Cuba, Jean (1501). Garden Of Health (in French). Verard Antoine (Paris). Archived from the original (758 scanned pages with black & white illustrations) on 2007.

- Hortus sanitatis deutsch. Mainz (Peter Schöffer) 1485; Neudrucke München 1924 and 1966.

- Clark, Willene B.; McMunn, Meradith T. (2005). "Introduction". In Clark, Willene B.; McMunn, Meradith T. (eds.). Beasts and Birds of the Middle Ages. The Bestiary and Its Legacy. Nation Books. pp. 2–4. ISBN 0-8122-8147-0.

- McCulloch, Florence (1962). Mediaeval Latin and French Bestiaries. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 3.

- Lindberg, David C. (1992). The Beginnings of Western Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 354-356. ISBN 0-226-48231-6.

- "Fearsome Creatures of Florida by John Henry Fleming". Fearsomecreatures.com. Retrieved 2016-12-06.

- "The Book of Barely Imagined Beings". Barelyimaginedbeings.com. Retrieved 2016-12-06.

- "Religion News Association & Foundation". Rna.org. 2016-11-21. Archived from the original on 2014-10-19. Retrieved 2016-12-06.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bestiaries. |

- The Bestiary: The Book of Beasts, T.H. White's translation of a medieval bestiary in the Cambridge University library; digitized by the University of Wisconsin–Madison libraries.

- The Medieval Bestiary online, edited by David Badke.

- The Bestiaire of Philippe de Thaon at the National Library of Denmark.

- The Bestiary of Anne Walshe at the National Library of Denmark.

- The Aberdeen Bestiary at the University of Aberdeen.

- Exhibition (in English, but French version is fuller) at the Bibliothèque nationale de France

- Christian Symbolology Animals and their meanings in Christian texts.

- Bestiairy - Monsters & Fabulous Creatures of Greek Myth & Legend with pictures