Bernoulli's inequality

In mathematics, Bernoulli's inequality (named after Jacob Bernoulli) is an inequality that approximates exponentiations of 1 + x. It is often employed in real analysis.

The inequality states that

for every integer r ≥ 0 and every real number x ≥ −1.[1] If the exponent r is even, then the inequality is valid for all real numbers x. The strict version of the inequality reads

for every integer r ≥ 2 and every real number x ≥ −1 with x ≠ 0.

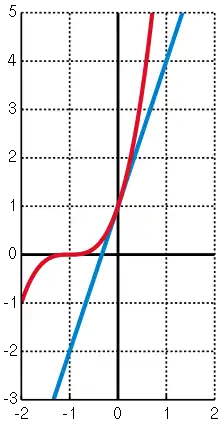

There is also a generalized version that says for every real number r ≥ 1 and real number x ≥ −1,

while for 0 ≤ r ≤ 1 and real number x ≥ −1,

Bernoulli's inequality is often used as the crucial step in the proof of other inequalities. It can itself be proved using mathematical induction, as shown below.

History

Jacob Bernoulli first published the inequality in his treatise “Positiones Arithmeticae de Seriebus Infinitis” (Basel, 1689), where he used the inequality often.[2]

According to Joseph E. Hofmann, Über die Exercitatio Geometrica des M. A. Ricci (1963), p. 177, the inequality is actually due to Sluse in his Mesolabum (1668 edition), Chapter IV "De maximis & minimis".[2]

Proof of the inequality

We proceed with mathematical induction in the following form:

- we prove the inequality for ,

- from validity for some r we deduce validity for r + 2.

For r = 0,

is equivalent to 1 ≥ 1 which is true.

Similarly, for r = 1 we have

Now suppose the statement is true for r = k:

Then it follows that

since as well as . By the modified induction we conclude the statement is true for every non-negative integer r.

Generalizations

Generalization of exponent

The exponent r can be generalized to an arbitrary real number as follows: if x > −1, then

for r ≤ 0 or r ≥ 1, and

for 0 ≤ r ≤ 1.

This generalization can be proved by comparing derivatives. Again, the strict versions of these inequalities require x ≠ 0 and r ≠ 0, 1.

Generalization of base

Instead of the inequality holds also in the form where are real numbers, all greater than -1, all with the same sign. The Bernoulli's inequality is special case when . This generalized inequality can be proved by mathematical induction.

Proof

In the first step we take . In this case inequality is obviously true.

In the second step we assume validity of inequality for numbers and deduce validity for numbers.

We assume that

is valid. After multiplying both sides with a positive number we get:

As have all equal sign, the products are all positive numbers. So the quantity on the right-hand side can be bounded as follows:

what was to be shown.

Related inequalities

The following inequality estimates the r-th power of 1 + x from the other side. For any real numbers x, r with r > 0, one has

where e = 2.718.... This may be proved using the inequality (1 + 1/k)k < e.

Alternative form

An alternative form of Bernoulli's inequality for and is:

This can be proved (for any integer t) by using the formula for geometric series: (using y = 1 − x)

or equivalently

Alternative proof

Using AM-GM

An elementary proof for and x ≥ -1 can be given using weighted AM-GM.

Let be two non-negative real constants. By weighted AM-GM on with weights respectively, we get

Note that

and

so our inequality is equivalent to

After substituting (bearing in mind that this implies ) our inequality turns into

which is Bernoulli's inequality.

Using the formula for geometric series

Bernoulli's inequality

-

(1)

is equivalent to

-

(2)

and by the formula for geometric series (using y = 1 + x) we get

-

(3)

which leads to

-

(4)

Now if then by monotony of the powers each summand , and therefore their sum is greater and hence the product on the LHS of (4).

If then by the same arguments and thus all addends are non-positive and hence so is their sum. Since the product of two non-positive numbers is non-negative, we get again (4).

Using the binomial theorem

One can prove Bernoulli's inequality for x ≥ 0 using the binomial theorem. It is true trivially for r = 0, so suppose r is a positive integer. Then Clearly and hence as required.

Notes

- Brannan, D. A. (2006). A First Course in Mathematical Analysis. Cambridge University Press. p. 20. ISBN 9781139458955.

- mathematics - First use of Bernoulli's inequality and its name - History of Science and Mathematics Stack Exchange

References

- Carothers, N.L. (2000). Real analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-521-49756-5.

- Bullen, P. S. (2003). Handbook of means and their inequalities. Dordercht [u.a.]: Kluwer Academic Publ. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-4020-1522-9.

- Zaidman, S. (1997). Advanced calculus : an introduction to mathematical analysis. River Edge, NJ: World Scientific. p. 32. ISBN 978-981-02-2704-3.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Bernoulli Inequality". MathWorld.

- Bernoulli Inequality by Chris Boucher, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Arthur Lohwater (1982). "Introduction to Inequalities". Online e-book in PDF format.