Bürgi–Dunitz angle

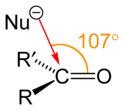

The Bürgi–Dunitz angle (BD angle) is one of two angles that fully define the geometry of "attack" (approach via collision) of a nucleophile on a trigonal unsaturated center in a molecule, originally the carbonyl center in an organic ketone, but now extending to aldehyde, ester, and amide carbonyls, and to alkenes (olefins) as well.[2][3][4] Precisely, in the case of nucleophilic attack at a carbonyl, it is defined as the Nu-C-O bond angle, where Nu is used here to identify the atom of the nucleophile that forms the bond with the carbon atom, C. The angle was named after crystallographers Hans-Beat Bürgi and Jack D. Dunitz, its first senior investigators. The second angle defining the geometry describes the "offset" of the nucleophile's approach toward one of the two substituents attached to the carbonyl carbon or other electrophilic center, and was named the Flippin–Lodge angle by Clayton Heathcock after his contributing collaborators Lee A. Flippin and Eric P. Lodge.[5] These angles are generally construed to mean the angle measured or calculated for a given system, and not the historically observed value range for the original Bürgi–Dunitz aminoketones, or an idealized value computed for a particular system (such as hydride addition to formaldehyde, image at left). That is, the BD and FL angles of the hydride-formadehyde system produce a given pair of values, while the angles observed for other systems may vary relative to this simplest of chemical systems.[2][4][6]

The BD angle adopted during an approach by a nucleophile to a trigonal unsaturated electrophile depends primarily on the molecular orbital (MO) shapes and occupancies of the unsaturated carbon center (e.g., carbonyl center), and only secondarily on the molecular orbitals of the nucleophile.[2] The original Bürgi-Dunitz measurements were of a series of intramolecular amine-ketone carbonyl interactions, in crystals of compounds bearing both functionalities—e.g., methadone and protopine (images at left and right). These gave a narrow range of BD angle values (105 ± 5°); corresponding computations—molecular orbital calculations of the SCF-LCAO-type—describing the approach of the s-orbital of a hydride anion (H−) to the pi-system of the simplest aldehyde, formaldehyde (H2C=O), gave a BD angle value of 107°.[3] Hence, Bürgi, Dunitz, and thereafter many others noted that the crystallographic measurements of the aminoketones and the computational estimate for the simplest nucleophile-electrophile system were quite close to a theoretical ideal, the tetrahedral angle (internal angles of a tetrahedron, 109.5°), and so consistent with a geometry understood to be important to developing transition states in nucleophilic attacks at trigonal centers.

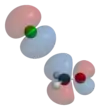

The convergence of observed BD angles can be viewed as arising from the need to maximize overlap between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) of the nucleophile, and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of the unsaturated, trigonal center of the electrophile.[2] (See, in comparison, the related inorganic chemistry concept of the angular overlap model.[7][8][9]) In the case of addition to a carbonyl, the HOMO is often a p-type orbital as shown in the figure (e.g., on an amine nitrogen or halide anion), and the LUMO is generally understood to be the antibonding π* molecular orbital perpendicular to the plane containing the ketone C=O bond and its substituents (see figure at right above). The BD angle observed for nucleophilic attack is believed to approach the angle that would produce optimal overlap between HOMO and LUMO (based on the principle of the lowering of resulting new MO energies after such mixing of orbitals of similar energy and symmetry from the participating reactants). At the same time, the nucleophile avoids overlap with other orbitals of the electrophilic group that are unfavorable for bond formation (not apparent in image at right, above, because of the simplicity of the R=R'=H in formaldehyde).

To understand cases of real chemical reactions, the HOMO-LUMO-centered view is modified by understanding of further complex, electrophile-specific repulsive and attractive electrostatic and van der Waals interactions that alter the altitudinal BD angle, and bias the azimuthal Flippin-Lodge angle toward one substituent or the other (see graphic above).[10] In addition, any dynamics at play in the system (e.g., easily changed torsional angles) are taken into account in real cases. (Recall, BD angle theory was developed based on "frozen" interactions in crystals; much of the chemistry of general interest and use takes place via collisions of molecules tumbling in solution.) Moreover, in constrained reaction environments such as in enzyme and nanomaterial binding sites, early evidence suggests that BD angles for reactivity can be quite distinct, since reactivity concepts assuming orbital overlaps during random collision are not directly applicable.[11][6] For instance, the BD value determined for enzymatic cleavage of an amide by a serine protease (subtilisin) was 88°, quite distinct from the hydride-formaldehyde value of 107°; moreover, compilation of literature crystallographic BD angle values for the same reaction mediated by different protein catalysts clustered at 89 ± 7° (i.e., only slightly offset from directly above or below the carbonyl carbon). At the same time, the subtilisin FL value was 8°, and FL angle values from the careful compilation clustered at 4 ± 6° (i.e., only slightly offset from directly behind the carbonyl; see the Flippin–Lodge angle article).[6]

Practically speaking, the Bürgi–Dunitz and Flippin–Lodge angles were central to the development of understanding of chiral chemical synthesis, and specifically of the phenomenon of asymmetric induction during nucleophilic attack at hindered carbonyl centers (see the Cram–Felkin–Anh and Nguyen models).[5][12] As well, the stereoelectronic principles that underlie nucleophiles adopting a proscribed range of Bürgi–Dunitz angles may contribute to the conformational stability of proteins[13][14] and are invoked to explain the stability of particular conformations of molecules in one hypothesis of a chemical origin of life.[15]

See also

References

- Hall, S. R.; Ahmed, F. R. (1968). "The crystal structure of protopine, C20H19O5N". Acta Crystallogr. B. 24 (3): 337–346. doi:10.1107/S0567740868002347.

- Fleming, I. (2010) Molecular Orbitals and Organic Chemical Reactions: Reference Edition, John Wiley & Sons, pp. 214–215.

- Bürgi, H.-B.; Dunitz, J. D.; Lehn. J.-M.; Wipff, G. (1974). "Stereochemistry of reaction paths at carbonyl centres". Tetrahedron. 30 (12): 1563–1572. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)90678-7.

- Cieplak, A.S. (2008) Organic addition and elimination reactions: Transformation paths of carbonyl derivatives In Structure Correlation, Vol. 1 (H.-B. Bürgi & J. D. Dunitz, eds.), New York:John Wiley & Sons, pp. 205–302, esp. 216-218. [doi:10.1002/9783527616091.ch06; ISBN 9783527616091 ]

- Heathcock, C.H. (1990) Understanding and controlling diastereofacial selectivity in carbon-carbon bond-forming reactions, Aldrichimica Acta 23(4):94-111, esp. p. 101, see , accessed 9 June 2014.

- Radisky, E.S. & Koshland, D.E. (2002), A clogged gutter mechanism for protease inhibitors, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 99(16):10316-10321, see , accessed 28 November 2014.

- Hoggard, P.E. (2004) Angular overlap model parameters, Struct. Bond. 106, 37.

- Burdett, J.K. (1978) A new look at structure and bonding in transition metal complexes, Adv. Inorg. Chem. 21, 113.

- Purcell, K.F. & Kotz, J.C. (1979) Inorganic Chemistry, Philadelphia, PA:Saunders Company.

- Lodge, E.P. & Heathcock, C.H. (1987) Steric effects, as well as sigma*-orbital energies, are important in diastereoface differentiation in additions to chiral aldehydes, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 109:3353-3361.

- See for instance, Light, S.H.; Minasov, G.; Duban, M.-E. & Anderson, W.F. (2014) Adherence to Bürgi-Dunitz stereochemical principles requires significant structural rearrangements in Schiff-base formation: Insights from transaldolase complexes, Acta Crystallogr. D 70(Pt 2):544-52, DOI: 10.1107/S1399004713030666, see , accessed 10 June 2014.

- Gawley, R.E. & Aube, J. 1996, Principles of Asymmetric Synthesis (Tetrahedron Organic Chemistry Series, Vo. 14), pp. 121-130, esp. pp. 127f.

- Bartlett, G.J.; Choudhary, A.; Raines, R.T.; Woolfson, D.N. (2010). "n→π* interactions in proteins". Nat. Chem. Biol. 6 (8): 615–620. doi:10.1038/nchembio.406. PMC 2921280. PMID 20622857.

- Fufezan, C. (2010). "The role of Buergi‐Dunitz interactions in the structural stability of proteins". Proteins. 78 (13): 2831–2838. doi:10.1002/prot.22800. PMID 20635415. S2CID 41838636.

- Choudhary, A.; Kamer, K.J.; Powner, M.W.; Sutherland, J.D.; Raines, R.T. (2010). "A stereoelectronic effect in prebiotic nucleotide synthesis". ACS Chem. Biol. 5 (7): 655–657. doi:10.1021/cb100093g. PMC 2912435. PMID 20499895.