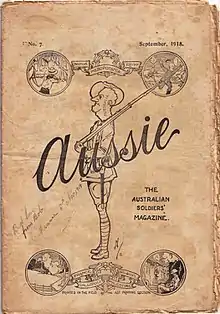

Aussie: The Australian Soldiers' Magazine

Aussie: The Australian Soldiers' Magazine was a magazine printed in the field on the Western Front, in France, during World War One by the Australian Imperial Forces Printing Section. The publication was an incredible endeavour that helped to celebrate the distinctive Australian identity at war, as well as shaping a sense of community and played a significant role in articulating what it meant to be a 'digger'.

| Editor: Lieut. Phillip Harris |

| First Issue Published: January 18, 1918. |

| Ceased Publication: 1932. |

It was started in 1918 by Lieut. Phillip L. Harris, a former journalist who was to become its first and only editor.[1] Harris acquired a small printing plant and accessories from various firms in Sydney and Melbourne in 1914, and the press was first used on the troopship Ceramic to produce a small regimental paper, Honk![2] The plant consisted of a Platen press, type and accessories, and a small amount of paper. In 1916 the press was then used to produce a paper called The Rising Sun, which was only in print for three months, following which Harris presented the idea of making a magazine for Australian troops on the front-line.[2] Despite facing the extreme difficulties of finding an adequate supply of paper and skilled help, Harris was able to print 10,000 copies of the first issue of Aussie in the field at Flêtre.[3] The thirteen issues of the magazine were sold to the troops for ten centimes a copy, with much of the proceeds going to the A.I.F Trust Fund,[2] and to raise money for Australia's national War Museum.[2]

The magazine contained some biographical clips and works by well-known Australian writers such as 'Banjo' Paterson, Henry Lawson, C.J Dennis, Louise Mack and John Le Gay Brereton. Most of the troops would have been familiar with these writers due to the popularity as contributors to The Bulletin. But the majority of Aussie's content came from the diggers (soldiers) themselves. Harris claimed that the articles within the magazine were stories from the soldiers, and he "merely caught them and put them on to paper".[2] Aussie was a magazine for Australian soldiers, made by Australian soldiers and as Sir Colin Hines put it, the magazine "shows in its humour, pathos, and tales of comradeship, the spirit which created the entity of the Australian at War" (Harris, i)[2]

Aussie in the field

The first issue of Aussie was printed in the field at Fletre on January 18, 1918.[2] Ten thousand copies were printed of the sixteen page volume. For most of its wartime publication the magazine was wholly put together by Lieut. Phillip Harris with the help of a member of Harris' battalion, Bill Littleton.[2] The first issue found success and there was demand for sixty thousand copies of the second issue. However, the small Platen printing press being used for the magazine was only able to print one page at a time, making it impractical and almost impossible to print sixty thousand copies on that equipment. Harris went in search of a new printing press, looking through the remains of villages that had been shelled. Most of the machines that he came across had been too badly damaged, but Harris was able to pull one from the wreckage at Dunkirk.[2] The machine had been damaged but was brought back to life by the Australian troops. Harris still faced the challenge of sourcing enough paper to print the magazine, collecting it from various ruined printing works near the Line and a paper mill near Saint Omer.[2] As the magazine continued, sourcing paper remained an issue until Harris discovered a printing works in a cellar in Armentieres. Harris had picked up on a consistent habit of printers to move their machinery and supplies into basements as warfare moved through the towns and so searched through the ruins of Armentieres until he came across the printing works and ten tons of paper, enabling the printing of 100,000 copies of the third issue of Aussie. With this many copies of the third issue, Harris was unable to get a sufficient labour to fold the sheets of the magazine. Harris searched through a number of towns for a folding machine but came up empty handed. It wasn't until one was donated by Lady McIlwraith that the third issue was able to be completed. Sourcing paper remained an issue for Harris, until he eventually approached Brig-General Dodds with his problem. Dodds organised with the War Office to send three tons of paper per issue from London.[2]

Before the fourth issue was printed the printing plant was moved from Fletre to Fauquembergues, both of which were subsequently bombed by German forces in April, 1918.[3] The press was damaged, but remained in working order. To ensure the accurate representation of soldiers on the front line, Harris would travel by lorry or troop-train to the frontline to gather his material from the troops for following issues. The final three issues of the wartime Aussie magazine were then printed in Marchienne-au-Pont after the Armistice. By the end of the war Aussie had a circulation of 80-100,000 and a reputation as the leading Australian troop publication, being praised as "'the most remarkable trench paper on any front during the war'" (Laugesen, 15).[1]

After the war

Following the end of the war Harris repatriated Aussie and published an issue of Aussie "now in civvies" (Lindesay, 95).[3] The peacetime magazine was titled Aussie: The Cheerful Monthly and was to retain the good humour, stories and cartoons that made the field magazine so popular and sustain that digger culture and community. It was only ever intended as a commercial magazine of good humour, opinions and literary works and commentary. It was published by one of Sydney's major presses, New Century Press, which also published Lone Hand, Humour magazine and the Australian Quarterly.[4] The new Aussie featured colour covers, and a thicker issue of sixty-one larger pages printed on quality paper.[3] Aussie didn't employ permanent staff writers or artists, instead continuing its previous set up of featuring freelance submissions. Some of the better known contributors included Roderic Quinn, A.G. Stephens, Fred Bloomfield, Les Robinson, Myra Morris, Will Lawson, Hugh McCrae and illustrators Emile Mercier, Cecil White, Percy Lindsay, Esther and Betty Paterson and Mick Armstrong.[3]

Aussie attempted to move further into civilian life, at first mimicking the wartime magazine before altering its layout to incorporate more lifestyle feature articles and women's pages.[5] In 1923 Harris was succeeded as publisher by the husband of Henry Lawson's daughter Bertha, Walter Jago, as editor. Jago had previously been working as a freelance writer and editor of the Lone Hand 1919-1921.[4]

By 1924 the new civilian Aussie had reached the original's circulation of 100,000 before the magazine readership began to decline, leading to its eventual collapse in 1932. In a promotion of the returned soldiers continued honour as exemplary citizens, Aussie created the character of 'Dave' who was a witty bushman, the quintessential returned digger now supporting the Australian pastoral community. This was coupled with articles and cartoons that dealt with the returned servicemen's struggle to return to work or to start new careers after the war. Many returned soldiers were dealing with varying forms of post-traumatic stress or were simply returned to their previous employment to find their job now belonged to someone else.[4]

The Editor

Lieutenant Phillip Harris was a journalist from a publishing family who ran the Hebrew Standard from George Street in Sydney.[4] Harris was also a contributor to other publications such as The Bulletin and Lone Hand. He enlisted in the army in 1914 and quickly rose through the ranks. The idea for Aussie began in November, 1914 when Harris first collected the small Platen printing plant and accessories from various firms in Sydney and Melbourne before heading off to war.[2] At the end of 1917 Harris pitched the idea of Aussie to Major-General Sir C.B.B. White who was then Chief-of-Staff of the Australian Corps, and Harris was given the go-ahead to put together the trench magazine.[2] Harris then created one of the most successful wartime magazines and brought it back to Australian shores after the war. In 1922 Lieut. Harris and George Robertson, of Angus and Robertson Book Publishers, were the ones to approach the state government to request a state funeral for the famous Australian writer, Henry Lawson. The request was turned down but Harris persisted and joined with Mary Gilmore to take the request all the way to the Prime Minister of Australia, Billy Hughes, who then ordered the funeral for the next day at St Andrew's Cathedral in Sydney.[6]

Aussie's heavy use of slang, which Harris referred to as 'Slanguage',[2] that was both written and read by Australian soldiers helped to create a sense of separate national character from that of the British or American soldiers. Well used slang terms included "'cobber', 'dinkum', and 'furphy'" (Laugesen, 16),[1] with the first issue of Aussie leaving room for an Aussie Dictionary of slang which was labelled as 'For the use of those at Home'.[2] Harris knew the Australian digger as a man who would put humour into everything. A man whose humour was "more spontaneous than that of the Yank… the Yank was funny, the Aussie witty" (Harris, 3)[2] Aussie was an extremely significant publication in Australian history – one that created and nurtured national identity and pride for Australian soldiers fighting in France during World War One, as well as going on to become a significant publication for returned servicemen and the general public following the war. Many writers and artists began their careers with Aussie,[3] and the magazine also played a role in furthering the readership of some of the literary greats of this country. It is a magazine to be noted as a significant part of Australian history and nation building.

References

- Laugesen, Amanda (2003). ""Aussie Magazine and the Making of Digger Culture during the Great War."". National Library of Australia News.

- Harris, Phillip (1920). "Aussie: The Australian Soldier's Magazine." Aussie. Western Australia: Veritas Publishing Company. pp. i-3.

- Lindesay, Vane (1983). The Way We Were: Australian Popular Magazines 1856 to 1969. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. pp. 87–97.

- Carter, David (2008). ""'Esprit De Nation' and Popular Modernity: Aussie Magazine 1920–1931"". History Australia. 5:3: 74.1–74.22.

- Chapman, Jane (2016). ""The Aussie 1918-1931: Cartoons, Digger Remembrance and First World War Identity"". Journalism Studies. 17, 4: 415–431.

- Moorhouse, Frank (2017). The Drover's Wife. North Sydney: Knopf. p. 15.

- Carter, David. "'Esprit De Nation' and Popular Modernity: Aussie Magazine 1920–1931," History Australia, 5:3, (2008) 74.1-74.22.

- Chapman, Jane. "The Aussie 1918-1931: Cartoons, Digger Remembrance and First World War Identity." Journalism Studies 17, no. 4 (2016): 415-431.

- Harris, Phillip L. and Australia. Australian Army. Australian Imperial Force (1914-1921). "Aussie: The Australian Soldier's Magazine." Aussie (1920).

- Harris, Phillip L. "Aussie Dictionary." Aussie: The Australian Soldiers Magazine, no.1 (1918): 10-11.

- Laugesen, Amanda. "Aussie Magazine and the Making of Digger Culture during the Great War." National Library of Australia News 14, no. 2 (2003): 15-18.

- Lindesay, Vane. The Way We Were: Australian Popular Magazines 1856 to 1969. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1983.

- Moorhouse, Frank. The Drover's Wife. North Sydney: Knopf, 2017.