Arab Gas Pipeline

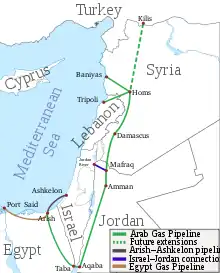

The Arab Gas Pipeline is a natural gas pipeline in the Middle East. It originates near Arish in the Sinai Peninsula and was built to export Egyptian natural gas to Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon, with branch underwater and overland pipelines to and from Israel. It has a total length of 1,200 kilometres (750 mi), constructed at a cost of US$1.2 billion.[1]

| Arab Gas Pipeline | |

|---|---|

Location of Arab Gas Pipeline | |

| Location | |

| Country | Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Turkey |

| General direction | south-north |

| From | Arish |

| Passes through | Aqaba, Amman, El Rehab, Deir Ali, Damascus, Baniyas, Aleppo |

| To | Homs, Tripoli, (Kilis) |

| General information | |

| Type | natural gas |

| Partners | EGAS ENPPI PETROGET GASCO SPC |

| Commissioned | 2003 |

| Technical information | |

| Length | 1,200 km (750 mi) |

| Maximum discharge | 10.3 billion cubic metres (360×109 cu ft) |

History

The pipeline has been used intermittently since its inauguration. Egyptian gas exports were reduced dramatically in 2011 – initially due to sabotage (mostly to its feeder pipeline in Sinai), followed by natural gas shortages in Egypt which forced it to discontinue gas exports by the mid 2010s. Sections of the pipeline continued to operate in Jordan to facilitate domestic transport of gas. The pipeline was reversed to flow gas from Jordan to Egypt from 2015 to 2018 (fed by imported LNG through Jordan's Aqaba LNG reception terminal). The recovery in Egyptian gas production has enabled gas to flow to Jordan through the link from 2018. In 2020 the pipeline also began distributing gas from Israel inside Jordan, while the underwater branch to Israel was reversed to allow gas from Israel to flow to Egypt.

Description

The main section of the pipeline through Egypt and Jordan is 36 inches (910 mm) in diameter, with compressor stations located approximately every 200 km – providing for a maximum annual gas discharge of 10.3 billion cubic meters (BCM). The pipeline's capacity could be increased by 50% by roughly doubling the number of compressor stations (to every 100 km).

Arish–Aqaba section

The first section of pipeline runs from Arish in Egypt to Aqaba in Jordan. It has three segments. The first 250 kilometres (160 mi) long overland segment links Al-Arish to Taba on the Red Sea. It also consists of a compressor station in Arish and a metering station in Taba. The second segment is a 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) long subsea segment from Taba to Aqaba. The third segment, which also includes a metering station, is a 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) long onshore connection to the Aqaba Thermal Power Station.[2]

The $220 million Arish–Aqaba section was completed in July 2003.[3] The diameter of the pipeline is 36 inches (910 mm) and has a capacity of 10.3 billion cubic metres (360 billion cubic feet) of natural gas per year.[4] The Egyptian consortium that developed this section included EGAS, ENPPI, PETROGET and the Egyptian Natural Gas Company (GASCO).

Aqaba–El Rehab section

The second section extended the pipeline in Jordan from Aqaba through Amman to El Rehab, (24 kilometres (15 mi) from the Syrian border). The length of this section is 390 kilometres (240 mi) and it cost $300 million.[5] The second section was commissioned in 2005.

Israel–Jordan connection

As of 2018, a 65 km, 36 inches (910 mm) pipeline is under construction from the Jordan River near kibbutz Neve Ur on the Israel-Jordan border that will connect to the Arab Gas Pipeline near Mafraq in northern Jordan. Inside Israel the pipeline extends 23 km from the border with Jordan to near kibbutz Dovrat in the Jezreel Valley where it connects to the existing Israeli domestic natural gas distribution network. The pipeline is expected to be completed in mid-2019 and will supply Jordan with 3 BCM of natural gas per year starting in 2020.[6]

A 12 inches (300 mm) gas pipeline from Israel also supplies the Jordanian Arab Potash factories near the Dead Sea, however it is located far from the Arab Gas Pipeline and is not connected to it.

El Rehab–Homs section

The third section has a total length of 319 kilometres (198 mi) from Jordan to Syria. A 90 kilometres (56 mi) stretch runs from the Jordan–Syrian border to the Deir Ali power station. From there the pipeline runs through Damascus to the Al Rayan gas compressor station near Homs. This sections includes four launching/receiving stations, 12 valve stations and a fiscal metering station with a capacity of 1.1 billion cubic metres (39 billion cubic feet), and it supplies Tishreen and Deir Ali power stations. The section was completed in February 2008, and it was built by the Syrian Petroleum Company and Stroytransgaz, a subsidiary of Gazprom.[7][8]

Homs–Tripoli connection

The Homs–Tripoli connection runs from the Al Rayan compressor station to Baniyas in Syria and then via 32-kilometre (20 mi) long stretch to Tripoli, Lebanon. The agreement to start supplies was signed on 2 September 2009 and test run started on 8 September 2009.[4] Regular gas supplies started on 19 October 2009 and gas is delivered to the Deir Ammar power station.[9]

There is a proposal to extend the branch from Banias to Cyprus.[10]

Syria–Turkey connection

In 2006 Egypt, Syria, Jordan, Turkey, Lebanon, and Romania reached an agreement to build the pipeline's extension through Syria to the Turkish border. From there, the pipeline would have been connected to the proposed Nabucco Pipeline for the delivery of gas to Europe. Turkey forecasted buying up to 4 billion cubic metres per annum (140 billion cubic feet per annum) of natural gas from the Arab Gas Pipeline.[11] In 2008 Turkey and Syria signed an agreement to construct a 63 kilometres (39 mi) pipeline between Aleppo and Kilis as a first segment of the Syria-Turkey connection of the Arab Gas Pipeline[12][13] and Stroytransgaz signed a US$71 million contract for the construction of this section.[14] However, this contract was annulled at the beginning of 2009 and re-tendered. This section was awarded to PLYNOSTAV Pardubice Holding, a Czech Contracting Company, who finished the project in May 2011. From Kilis, a 15-kilometre (9.3 mi) long pipeline with a diameter of 12 inches (300 mm) would connect the pipeline with the Turkish grid thus allowing the Turkish grid to be supplied via the Syrian grid even before completing the Homs–Aleppo segment.

Arish–Ashkelon pipeline

The Arish–Ashkelon pipeline is a 90-kilometre (56 mi) long submarine gas pipeline with a diameter of 26 inches (660 mm), connecting the Arab Gas Pipeline with Israel. The physical capacity of the pipeline is 7 billion cubic metres (250 billion cubic feet) of gas per year, although technical upgrades can increase its capacity to a total of 9 billion cubic metres (320 billion cubic feet) per year. While it is not officially a part of the Arab Gas Pipeline project, it branches off from the same pipeline in Egypt. The pipeline is built and operated by the East Mediterranean Gas Company (EMG), a joint company of Mediterranean Gas Pipeline Ltd (28%), the Israeli company Merhav (25%), PTT (25%), EMI-EGI LP (12%), and Egyptian General Petroleum Corporation (10%).[15] The pipeline became operational in February 2008, at a cost of $180–$550 million (the exact figure is disputed).[16] It has since ceased operation due to sabotage of its feeder pipeline in Sinai and gas shortages in Egypt. However, although originally intended for transporting gas from Egypt to Israel, the gas shortages in Egypt have raised the possibility of operating the pipeline in the opposite direction, i.e., from Israel to Egypt beginning in 2019.[17]

Initial supply agreement

Egypt and Israel had originally agreed to supply through the pipeline 1.7 billion cubic metres (60 billion cubic feet) of natural gas per year for use by the Israel Electric Corporation.[18] This amount was later raised to 2.1 billion cubic metres (74 billion cubic feet) per year to be delivered through the year 2028. In addition, by late 2009, EMG signed contracts to supply through the pipeline an additional 2 billion cubic metres (71 billion cubic feet) per year to private electricity generators and various industrial concerns in Israel and negotiations with other potential buyers were ongoing. In 2010, the pipeline supplied approximately half of the natural gas consumed in Israel, with the other half being supplied from domestic resources. With the capacity to supply 7 billion cubic metres (250 billion cubic feet) per year, it made Israel one of Egypt's most important natural gas export markets. In 2010 some Egyptian activists appealed for a legal provision against governmental authorities to stop gas flow to Israel according to the obscure contract and very low price compared to the global rates, however the provision was denied by Mubarak regime for unknown reasons. In 2011, after the Egyptian revolution against Mubarak regime, many Egyptians called for stopping the gas project with Israel due to low prices. After a fifth bombing of the pipeline, flow had to be stopped for repair.[19][20]

2012 cancellation

Following the removal of Hosni Mubarak as head of state, and a perceived souring of ties between the two states, the standing agreement fell into disarray. According to Mohamed Shoeb, the head of the state-owned EGAS, the "decision we took was economic and not politically motivated. We canceled the gas agreement with Israel because they have failed to meet payment deadlines in recent months". Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu also said that according to him the cancellation was not "something that is born out of political developments". However, Shaul Mofaz said that the cancellation was "a new low in the relations between the countries and a clear violation of the peace treaty".[21] Eventually, gas shortages forced Egypt to cancel most of its export agreements to all countries it previously sold gas to in order to meet internal demand.

Litigation and settlement

The Egyptian state entities supplying the pipeline attempted to declare force majeure in cancelling the gas agreement with EMG and the Israel Electric Corporation, while the latter contented the cancellation amounted to a unilateral breach of contract. The matter was referred to the International Court of Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce in Geneva. After four years of proceedings the arbitration panel ruled against Egypt and ordered it to pay approximately US$2 billion in fines and damages to EMG and the IEC for unilaterally cancelling the contract. Egypt then appealed the panel's decision to the Swiss courts, who also ruled against Egypt in 2017.[22][23] Eventually, a settlement over the fine was reached in 2019 underwhich Egypt will pay the IEC US$500 million over the course of 8.5 years as compensation for halting the gas supplies. The settlement clears the way for gas exports from Israel to Egypt to begin.[24]

Reverse flow agreement

Since the Egyptian revolution, Egypt has been experiencing significant domestic shortages of natural gas, causing disruptions and financial losses to various Egyptian businesses who rely on it, as well as curtailing exports of natural gas from Egypt through the Arab Gas Pipeline (even during periods when it has been available for operation) and via LNG export terminals located in Egypt. This situation raised the possibility of using the Arish-Ashkelon Pipeline to send natural gas in the reverse mode.

In March 2015, the consortium operating Israel's Tamar gas field announced it reached an agreement, subject to regulatory approvals in both countries, for the sale of at least 5 billion cubic metres (180 billion cubic feet) of natural gas over three years through the pipeline to Dolphinus Holdings – a firm representing non-governmental, industrial and commercial consumers in Egypt.[25][26] In November 2015 a preliminary agreement for the export of up to 4 billion cubic metres per annum (140 billion cubic feet per annum) of natural gas from Israel's Leviathan gas field to Dolphinus via the pipeline was also announced.[27][28] The cost of rehabilitating the pipeline and converting it to allow for flow in the reverse direction is estimated at US$30 million.

In September 2018 it was announced that the consortium operating the Tamar and Leviathan fields and an Egyptian partner will spend US$518 million to buy a 39% stake in EMG in anticipation of beginning gas exports from Israel to Egypt through the Arish–Ashkelon pipeline.[29] Test flows through the pipeline from Israel to Egypt are expected to begin in summer 2019. If tests are successful, small amounts of gas will be exported on an interruptible basis until after the Leviathan field comes online in late 2019 at which point more substantial amounts could be supplied.

Discontinuation and resumption of service

The Egyptian pipelines carrying natural gas to Israel and Jordan stopped operating following at least 26 insurgent attacks since the start of the uprising in early 2011 until October 2014.[30] These attacks have mostly taken place on GASCO's pipeline in northern Sinai to El-Arish which feeds the Arab Gas Pipeline and the pipeline to Israel. The attacks have been carried out by Bedouin complaining of economic neglect and discrimination by the central Cairo government.[31][32] By spring 2013 the pipeline returned to continuous operation, however, due to persistent natural gas shortages in Egypt, the gas supply to Israel was suspended indefinitely while the supply to Jordan was resumed, but at a rate substantially below the contracted amount.[33] Since then the pipeline was targeted by militants several more times.

In the mid-2010s the pipeline did not export Egyptian gas due to domestic gas shortages which forced Egypt to stop exporting gas to all countries. Exports were resumed in 2018 as gas supply in Egypt was increased (thanks mainly to the Zohr gas field coming online). In 2020 it began distributing gas from Israel to Jordan through the Israel–Jordan pipeline connection in northern Jordan. With the reversing of the Arish–Ashkelon pipeline in Sinai and the northern Jordan connection it is now feasible to supply natural gas from Israel into the pipeline at two separate points which should make it more resilient to supply disruptions.

Timeline

On 5 February 2011, amidst the 2011 Egyptian protests an explosion was reported at the pipeline near the El Arish natural gas compressor station, which supplies pipelines to Israel and Jordan.[34][35][36][37][38] As a result, supplies to Israel and Jordan were halted.[39]

On 27 April 2011, an explosion at the pipeline near Al-Sabil village in the El-Arish region halted natural gas supplies to Israel and Jordan.[40] According to the Ministry of Petroleum and Mineral Resources unidentified saboteurs blew up a monitoring room of the pipeline.[41]

On 4 July 2011, an explosion at the pipeline near Nagah in the Sinai Peninsula halted natural gas supplies to Israel and Jordan.[42] An official said that armed men with machine guns forced guards at the station to leave before planting an explosive charge there.[42]

An overnight explosion on 26–27 September 2011 caused extensive damage to the pipeline at a location 50 kilometres (31 mi) from Egypt's border with Israel. As the pipeline had not been supplying gas to Israel since an earlier explosion in July, it did not affect Israel's natural gas supply. According to Egyptian authorities, local Bedouin Islamists were behind the attack.[43]

On 14 October 2014, an explosion targeted the pipeline for the 26th time near Al-Qurayaa region south east of El-Arish city.[44]

On 31 May 2015, the pipeline was targeted by unknown attackers for the 29th time.[45]

It was targeted by unknown assailants again on 7 January 2016, and Wilayat Sinai claimed responsibility.[46]

Between 2013 and 2018, the Aqaba–El Rehab section was the only section of the Arab Gas Pipeline outside Egypt that was in operation. It transported gas domestically within Jordan, mostly from an LNG reception terminal in Aqaba built after the discontinuation of gas imports from Egypt.

Starting in 2015 Egypt also occasionally used the Aqaba LNG terminal to import gas which was transported to Egypt in the reverse direction through the Arish–Aqaba section.

In 2018, Egypt resumed gas exports through the pipeline.

In 2020, exports of gas from Israel to Jordan through the Israel-Jordan pipeline connection in northern Jordan commenced. An agreement was also reached to allow gas from Israel to flow to Egypt over the Arab Gas Pipeline fed by the Israel-Jordan connection via Jordan and Sinai.

Exports of gas from Israel to Egypt through the Arish–Ashkelon pipeline began in 2020.

On 24 August 2020, an attack on a section of the pipeline north of Damascus caused widespread power outages in Syria.[47]

References

- "Lebanon minister in Syria to discuss the Arab Gas Pipeline". Ya Libnan. 23 February 2008. Archived from the original on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 10 March 2008.

- "Natural Gas Pipeline (Al-Arish – Aqaba). Project fact sheet". The Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development. Archived from the original on 5 April 2008. Retrieved 12 August 2008.

- "Arab gas pipeline agreement". Gulf Oil & Gas. 26 January 2004. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- "Arab Gas Pipeline Primes Lebanon Branch". Oil and Gas Insight. 4 September 2009. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- "Iraq Joins the Arab Gas Pipeline Project". Gulf Oil & Gas. 26 September 2004. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- Ghazal, Mohammad (5 July 2018). "Israeli gas to Jordan expected in 2020 — official". The Jordan Times. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- "Syria Completes First Stage of Arab Gas Pipeline". Downstream Today. Xinhua News Agency. 18 February 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- "Stroitransgaz wins tender to build the third part of Arab gas pipeline". The Canadian Trade Commissioner Service. November 2005. Archived from the original on 12 July 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2008.

- "Lebanon Receives Egypt Gas To Run Power Plant". Downstream Today. McClatchy-Tribune Information Services. 20 October 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- "Timetable for extending Arab gas pipelines inside Jordan and Syria discussed". ArabicNews.com. 25 September 2004. Archived from the original on 22 October 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- "Ministers agree to extend Arab gas pipeline to Turkey". Alexander's Gas & Oil Connections. 29 March 2006. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- "Syria to Buy Iranian Gas Via Turkey". Syria Times, BBC Monitoring. Downstream Today. 9 January 2008. Retrieved 14 January 2008.

-

"The Euro–Arab Mashreq Gas Market Project – Progress November 2007" (PDF). Euro-Arab Mashreq Gas Co-operation Centre. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Russians Build Turkey-Syria Pipeline". Kommersant. 14 October 2008. Archived from the original on 10 March 2010. Retrieved 26 October 2008.

- "PTT buys 25% of East Mediterranean Gas Co". Oil & Gas Journal. PennWell Corporation. 7 December 2007. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- Barkat, Amiram (27 September 2011). "IEC may seek partial ownership of Egyptian pipeline". Globes. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- Magdy, Mirette (8 October 2018). "Egypt to Receive First Israeli Gas as Early as March". Bloomberg. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Shirkani, Nassir (10 March 2008). "Egyptian gas flows to Israel". Upstream Online. NHST Media Group. (subscription required). Retrieved 10 March 2008.

-

"Egypt's Dilemma After Israel Attacks". Business Insider. Stratfor. 19 August 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

Such groups, whose ability to operate in this area depends heavily on cooperation from local Bedouins, have been suspected of responsibility for attacks on police stations and patrols as well as most if not all of five recent successful attacks on the El Arish natural gas pipeline that runs from Egypt to Israel.

-

Buck, Tobias; Saleh, Heba (18 August 2011). "Seventeen killed in Israel attacks". Financial Times. Jerusalem, Cairo. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

In the past six months, suspected Islamist militants in the Sinai have blown up a pipeline carrying natural gas to Israel five times.

- Sanders, Edmund (23 April 2012). "Egypt-Israel natural gas deal revoked for economic reasons". Los Angeles Times.

- Rigby, Ben (11 May 2017). "Egyptian companies lose major ICC energy dispute to Israel". African Law & Business. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- "Swiss court tells Egyptian energy companies to compensate Israel". Reuters. 28 April 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- "Egypt in $500 million settlement with Israel Electric Corp". Reuters. 16 June 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- Rabinovitch, Ari (18 March 2015). "Israel's Tamar group to sell gas to Egypt via pipeline". Reuters. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- Gutman, Lior (5 May 2015). "דולפינוס פתחה במו"מ עם EMG להולכת הגז ממאגר תמר למצרים" [Dolphinus commences negotiations for the use of EMG's pipeline] (in Hebrew). Calcalist. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- Scheer, Steven; Rabinovitch, Avi (25 November 2015). "Developers of Israel's Leviathan field sign preliminary Egypt gas deal". Reuters. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- Feteha, Ahmed; Elyan, Tamim (2 December 2015). "Egypt's Dolphinus Sees Gas Import Deal With Israel in Months". Reuters. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- Yaacov, Yaacov; Magdy, Mirette (27 September 2018). "Israel, Egypt Gas Partners Buy Control of Key Export Pipeline". Bloomberg. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- "Egyptian pipeline attacked for the 26th time". Youm7. 15 October 2014.

- Bar'el, Zvi (24 March 2012). "Economic distress, not ideological fervor, is behind Sinai's terror boom". Haaretz. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- Elyan, Tamim (1 April 2012). "Insight: In Sinai, militant Islam flourishes - quietly". Reuters. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- "Egyptian gas supply to Jordan stabilises at below contract rate". Al-Ahram. 3 June 2013. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- Sweilam, Ashraf (5 February 2011). "Egypt TV reports explosion, fire at gas pipeline in northern Sinai Peninsula near Gaza Strip". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- Blair, Edmund (5 February 2011). "Leaders inside, outside Egypt seek exit from impasse". Reuters. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- Issacharoff, Avi; Ravid, Barak (5 February 2011). "Egypt holds gas supply to Israel and Jordan after pipeline explosion". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 5 February 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- Razzouk, Nayla; Galal, Ola (5 February 2011). "Egypt Gas Exports to Israel, Jordan Halted After Sinai Pipeline Explosion". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 5 February 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- "Gas pipeline to Jordan, Syria set ablaze in Egypt". CNN. 5 February 2011. Archived from the original on 5 February 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- "Egypt gas pipeline attacked; Israel, Jordan flow hit". Reuters. 5 February 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- Saleh, Heba; Bekker, Vita (27 April 2011). "Gunmen attack Egyptian gas terminal". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- Razzouk, Nayla; Galal, Ola; Shahine, Alaa (27 April 2011). "Blast Hits Egypt-Israel Gas Pipeline, Forcing Supply Halt, Ministry Says". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- "Blast hits Egyptian gas pipeline". Al Jazeera. 4 July 2011. Archived from the original on 4 July 2011. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- "6th attack on Sinai gas pipeline". Globes. 27 September 2011. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- "For the 26th time, Egyptian gas pipeline attacked". youm7.com (in Arabic). 14 October 2014.

- Sweillam, Ashraf. "Natural gas pipeline blown up in Sinai". www.timesofisrael.com.

- "IS-linked militants claim attack on Sinai pipeline to Jordan". Middle East Eye.

- "Blast hits pipeline in Syria, causing wide power outages". AP NEWS. 24 August 2020.