Apracharajas

The Apracharajas (also known as Apracarajas, Apraca, Avacas) were an Indo-Scythian ruling dynasty of western Pakistan. The Apracharaja capital, known as Apracapura (also Avacapura), was located in the Bajaur district of the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Apraca rule of Bajaur existed from the 1st century BCE to the 1st century CE. Its rulers formed the dynasty which is referred to as the Apracharajas.

Apracharajas | |

|---|---|

| 15 BCE–50 CE | |

Approximate location of the Apracharajas. | |

| Capital | Bajaur |

| Common languages | Scythian language Prakrit (Kharoshthi script) Greek (coinage) |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| Government | Monarchy |

| Historical era | Antiquity |

• Established | 15 BCE |

• Disestablished | 50 CE |

Origins

Before the arrival of the Indo-Greeks and the Indo-Scythians, Apracan territory was the stronghold of the warlike Aspasioi tribe of Arrian, recorded in Vedic Sanskrit texts as Ashvakas. The Apracas are known in history for having offered a stubborn resistance to the Macedonian invader, Alexander the Great in 326 BCE.

The Indo-Scythians of the Apracharajas dynasty were successors of the Indo-Scythian king Azes. It seems that they established their dynasty from around 12 BCE.[1] Their territory seems to have centered in Bajaur and extended to Swat, Gandhāra, Taxila, and parts of eastern Afghanistan.[2]

Buddhism

The Apracharajas embraced Buddhism: they are known for their numerous Buddhist dedications on reliquaries. On their coins Hellenic designs, derived from the coinage of the Indo-Greeks, continued to appear alongside Buddhist ones.

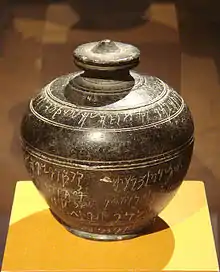

- Vijayamitra (ruled 12 BCE - 15 CE) personally dedicated in his name a Buddhist reliquary, the Shinkot casket.[4][5] Some of his coins bear the Buddhist triratna symbol.

- Indravarman, while still a Prince, personally dedicated in 5-6 CE a Buddhist reliquary, the Bajaur casket, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Numerous Buddhist dedications were made by the rulers of the Apracas:

"Members of the Apraca family in the northwestern borderlands of Pakistan and Afghanistan made numerous Buddhist donations recorded in Kharosṭḥī inscriptions dated in the era of Azes. Although most of these inscriptions lack specific provenance, the domain of the Aparacas was probably centered in Bajaur and extended to Swat, Gandhāra, Taxila, and parts of eastern Afghanistan in the last half of the first century BCE and the early decades of the first century CE. Since the discovery of an inscribed reliquary casket from Shinkot in Bajaur donated by the Apraca king Vijayamitra (who evidently founded the dynasty), other inscriptions record donations of relics by at least four generations of kings, queens, and court officials. Apraca kings known from Kharosṭḥī inscriptions, coins, and seals included Indravasu, Visṇuvarman (perhaps identical to Viśpavarman), and Indravarman, but the dynastic genealogy remains uncertain."

— Neelis, Jason, Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and Exchange.[6]

A recently discovered inscription in Kharoshthi on a Buddhist reliquary, the Bajaur reliquary inscription, gives a relationship between several eras of the period and mentions several Apraca rulers:

"In the twenty-seventh year in the reign of Lord Viyeemitro, the King of the Apraca; in the seventy-third year which is called the era of Azo, in the two hundred and first - 201 - year of the Yonas (Greeks), on the eighth day of the month of Sravana; on this day was established [this] stupa by Rukhana, the wife of the King of Apraca, [and] by Viyeemitro, the king of Apraca, [and] by Iṃdravarmo (Iṃdravaso), the commander (stratega), [together] with their wives and sons."

This inscription would date to c. 15 CE, according to the new dating for the Azes era which places its inception c. 47 BCE.[9] The rulers seem to have been related to Kharaostes.[10]

Dr. Prashant Srivastava, an Indian professor from the University of Lucknow, has in a research monograph highlighted the significant role played by the Apraca Dynasty rulers, and has connected the Apraca kings of Pakistan to the Ashvaka clan of Vedic literature.[11]

The Apraca kings are also mentioned in the Bajaur casket.[12]

Apraca Rulers and their Queens

- Vijayamitra (12 BCE - 15 CE), Queen: Rukhana

- Indravasu (c. 20 CE), Queen: Vasumitra

- Vispavarma or Visnuvarma, Queen: Śiśirena

- Iṃdravarmo, Queen: Utara

- Aspo [10] or Aspavarmo (15 - 45 CE)

- Sasan [10]

See also

References

- Greek Gods in the East, Stančo, Ladislav, Charles University in Prague, Karolinum Press, 2012, p.45

- Neelis, Jason, Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and Exchange., Brill, Leiden and Boston. 2011, pp. 117-118. ISBN 978 90 04 18159 5.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art notice

- "Afghanistan, carrefour en l'Est et l'Ouest" p.373. Also Senior 2003

- Des Indo-Grecs aux Sassanides, Rika Gyselen, Peeters Publishers, 2007, p.103

- Neelis, Jason, Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and Exchange. Brill, Leiden and Boston. 2011, pp. 117-118. ISBN 978 90 04 18159 5.

- Bopearachchi, O. (December 31, 2005). Afghanistan, ancien carrefour en l'Est et l'Ouest (in French). p. 373. ISBN 978-2503516813.

- Senior, R.C. (2006). Indo-Scythian coins and history. IV. Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. ISBN 978-0-9709268-6-9.

- Falk; Bennett (2009). Macedonian Intercalary Months and the Era of Azes.

- Salomon, Richard (1996). "An Inscribed Silver Buddhist Reliquary of the Time of King Kharaosta and Prince Indravarman". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 116 (3). University of Washington. p. 418. JSTOR 605147.

- Srivastava, Prashant (2007). The Apracharajas: A History Based on Coins and Inscriptions. University of Lucknow. ISBN 978-81-7320-074-8.

- Loeschner, Hans."Kanishka in Context with the Historical Buddha and Kushan Chronology." In: Glory of the Kushans – Recent Discoveries and Interpretations. Edited by Professor Vidula Jayasval, Aryan Books, New Delhi, 2013, p. 142.