Anne de Mortimer

Anne Mortimer, also known as Anne de Mortimer (27 December 1388 – c. 22 September 1411), was a medieval English noblewoman who became an ancestress to the royal House of York, one of the parties in the fifteenth-century dynastic Wars of the Roses. It was her line of descent which gave the Yorkist dynasty its claim to the throne. Anne was the mother of Richard, Duke of York, and thus grandmother of kings Edward IV and Richard III.

| Anne Mortimer | |

|---|---|

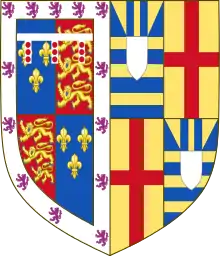

Coat of arms of Anne Mortimer[1] | |

| Born | 27 December 1388 |

| Died | c. 22 September 1411 (aged 22) |

| Burial | Kings Langley, Hertfordshire |

| Spouse | Richard of Conisburgh (m. 1408) |

| Issue Detail | |

| House | Mortimer |

| Father | Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March |

| Mother | Eleanor Holland |

Early life

Born on 27 December 1388,[2][3][4] Anne Mortimer was the eldest of the four children of Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March (1374–1398), and Eleanor Holland (1370–1405).[3] She had two brothers, Edmund, 5th Earl of March (1391–1425), and Roger (1393–1413?), as well as a sister, Eleanor.[3]

Anne's father was a descendant of Lionel, Duke of Clarence, second surviving son of King Edward III of England, an ancestry which made Mortimer a potential heir to the throne during the reign of the childless King Richard II. Upon Roger Mortimer's death in 1398, this claim passed to his son and heir, Anne's brother Edmund, Earl of March.[5] In 1399, Richard II was deposed by Henry IV, of the House of Lancaster, making Edmund Mortimer a dynastic threat to the new king, who in turn placed both Edmund and his brother Roger under royal custody.

Anne and her sister Eleanor remained in the care of their mother, Countess Eleanor, who, not long after her first husband's death, married Lord Edward Charleton of Powys.[5] Following their mother's death in 1405, the sisters fared less well than their brothers and were described as "destitute", needing £100 per annum for themselves and their servants.[6]

Marriage and issue

Around early 1408 (probably after 8 January),[7] Anne married Richard of Conisburgh (1385–1415), the second son of Edmund, Duke of York (fourth son of King Edward III). The marriage was undertaken secretly and probably with haste, without the knowledge of her nearest relatives, and was validated on 23 May 1408 by papal dispensation.[8]

Anne Mortimer and Richard of Conisburgh had two sons and a daughter:[9]

- Isabel of York (1409 – 2 October 1484), who in 1412, at three years of age, was betrothed to Sir Thomas Grey, son and heir of Sir Thomas Grey of Heaton (1384–1415), by whom she had one son.[10] Isabel married secondly, before 25 April 1426 (the marriage being later validated by papal dispensation), Henry Bourchier, 1st Earl of Essex, by whom she had issue.[11]

- Henry of York[12]

- Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York (22 September 1411 – 30 December 1460), Yorkist claimant to the English throne, and father of kings Edward IV and Richard III

Anne Mortimer died soon after the birth of her son Richard on 22 September 1411.[13] She was probably buried at Kings Langley, Hertfordshire, once the site of Kings Langley Palace,[14] perhaps in the conventual church that houses the tombs of her husband's parents Edmund of Langley and Isabella of Castile.

Ancestry

References

- Pinches, John Harvey; Pinches, Rosemary (1974), The Royal Heraldry of England, Heraldry Today, Slough, Buckinghamshire: Hollen Street Press, ISBN 0-900455-25-X

- Gransden 1992, p. 296.

- Tout 1894, p. 146.

- Dugdale, p. 355.

- Griffiths 2004.

- Griffiths 2004; CPR 1907, pp. 173, 392

- CPR 1907, p. 392.

- Pugh 1988, p. 94; Harriss 2012

- Richardson IV 2011, pp. 400–11.

- Burke's Peerage & Baronetage, 106th Edition, Charles Mosley Editor-in-Chief, 1999, Page: 15, 1222

- Richardson IV 2011, p. 402.

- Kirby 1995, entries 469, 472.

- Harriss 2012.

- Richardson IV 2011, p. 400.

- Mortimer, Ian (2007). The Fears of Henry IV: The Life of England's Self-made King. London: Jonathan Cape. pp. 459–460. ISBN 978-0-224-07300-4.

- Pollard, A.F. (1894). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 38. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Fotheringham, J.G. (1891). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 27. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Given-Wilson, C. (2004). "Fitzalan, Richard, third earl of Arundel". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online) (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9534. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Bibliography

- CPR (1907). Calendar of Patent Rolls, Henry IV, vol. 3: 1405–1408. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. hdl:2027/mdp.39015031079588.

- Dugdale, William (1849). John Caley; Henry Ellis & Bulkeley Bandinel (eds.). Monasticon Anglicanum. 6 (1) (new ed.). London: T.G. March. p. 355.

- Gransden, A. (1992). Legends, Traditions and History in Medieval England. London: Hambledon Press (published 1 July 1992). ISBN 978-1-85285-016-6.

- Griffiths, R.A. (2004). "Mortimer, Edmund (V), fifth earl of March". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online) (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/19344. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Harriss, G.L. (2012). "Richard, earl of Cambridge (1385–1415)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online) (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23502. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Kirby, J.L. (1995). Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem, Volume 20: Henry V, 1413–1418. London: HMSO. pp. 138–158.

- Pugh, T.B. (1988). Henry V and the Southampton Plot of 1415. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-86299-549-2.

- Richardson, D. (2011). Kimball G. Everingham (ed.). Magna Carta Ancestry. 4 (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. ISBN 978-1-4609-9270-8.

- Tout, T.F. (1894). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 39. London: Smith, Elder & Co.