Anicia Juliana

Anicia Juliana (Constantinople, 462 – 527/528) was a Late Antique Roman imperial princess, wife of the magister militum of the eastern Roman empire, Areobindus Dagalaiphus Areobindus, patron of the great Church of St Polyeuctus in Constantinople, and owner of the Vienna Dioscurides. She was the daughter of the Roman emperor Olybrius (r. 472) and his wife Placidia, herself the daughter of the emperor Valentinian III (r. 425–455) and Licinia Eudoxia, through whom Anicia Juliana was also great-granddaughter of the emperor Theodosius II (r. 408–450) and the sainted empress Aelia Eudocia. During the rule of the Leonid dynasty and the rise of the later Justinian dynasty, Anicia Juliana was thus the most prominent member of both the preceding imperial dynasties, the Valentinianic dynasty established by Valentinian the Great (r. 364–375) and the related Theodosian dynasty established by Theodosius the Great (r. 379–395).

.jpg.webp)

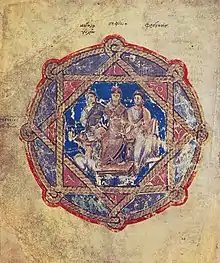

(Codex Vindobonensis med. gr. 1., folio 6v.)

Her son Olybrius Junior served as a Roman consul whilst only a child and married the niece of the emperor Anastasius I (r. 491–518), the daughter of Anastasius's brother Paulus. Despite Anicia Juliana's ambitions her son never became emperor, being ignored in the accession of Justin I (r. 518–527) after the death of Anastasius and the fall of the Leonid dynasty.

Life

She married Flavius Areobindus Dagalaiphus Areobindus, and their children included Olybrius, consul for 491. With her husband, she spent her life at the pre-Justinian court of Constantinople, of which she was considered "both the most aristocratic and the wealthiest inhabitant".[1]

Her glittering genealogy aside, Juliana is primarily remembered as one of the first non-reigning female patrons of art in recorded history. From what little we know about her personal predilections, it appears that she "directly intervened in determining the content, as well, perhaps, as the style" of the works she commissioned.[2]

Her pro-Roman political views, as espoused in her letter to Pope Hormisdas (preserved in the royal library of El Escorial) are reflected in the Chronicle of Marcellinus Comes, who has been associated with her literary circle. Whether Juliana entertained political ambitions of her own is uncertain, but it is known that her husband declined to take up the crown during the 512 riots. Although she resolutely opposed the Monophysite leanings of Emperor Anastasius, she permitted her son Olybrius to marry the Emperor's niece.[3]

Artistic patronage

Juliana's name is attached to the Vienna Dioscurides, also known as the Anicia Juliana Codex, an illuminated manuscript codex copy of Pedanius Dioscorides's De materia medica, known as the one of the earliest and most lavish manuscripts still in existence. It has a frontispiece with a donor portrait of Anicia Juliana, the oldest surviving such portrait in the history of manuscript illumination. The patrikia is shown enthroned and flanked by the personifications of Megalopsychia (Magnanimity) and Phronesis (Prudence), with a small female allegory labelled "Gratitude of the Arts" (Byzantine Greek: Eucharistia ton technon) performing proskynesis in honour of the patrikia, kissing her feet.[4] A putto is at Anicia Juliana's right side, handing her a codex and labelled with the Greek: ΠΟΘΟΣ ΤHΣ ΦΙΛΟΚΤΙΣΤΟΥ, romanized: pothos tes philoktistou, lit. 'yearning of the creation-lover', added in a later scribe's handwriting, interpreted as "the Desire to build", "the Love of building", or "the Desire of the building-loving woman".[4] The same hand has labelled the central figure as Sophia (Wisdom).[4]

The badly damaged encircling inscription proclaims Juliana as a great patron of art and identifies the people of Honoratae (a town on the Asiatic shore of the Bosporus) as having given the codex to Anicia Juliana.[4] She probably received the book in gratitude for her having built a church in the town.[4] The inscription is corroborated by the 8th–9th-century chronicler Theophanes Confessor in a notice of the year 512 that Anicia Juliana dedicated a church to the Theotokos in Honoratae that year.[4] Emphasizing her membership of the ancient patrician Anicia gens through her father Flavius Anicius Olybrius, the inscription reads:[4]

ΙΟΥ ΔΟΞΑΙϹΙ(Ν ΑΝΑϹϹΑ?) |

Hail, oh princess, Honoratae extols |

| —Codex Vindobonensis med. gr. 1. f. 6v.[5][6] | —translation from Iohannis Spatharakis (1976) and Bente Kiilerich (2001) |

Of her architectural projects, we know only three churches which she commissioned to be erected and embellished in Constantinople. The ornate basilica of St Polyeuctus was built on her extensive family estates during the last three years of her life, with the goal of highlighting her illustrious pedigree which ran back to Theodosius I and Constantine the Great. Until Justinian's extension of the Hagia Sophia, it was the largest church in the imperial capital, and its construction was probably seen as a challenge to the reigning dynasty.[7] The dedicatory inscription compares Juliana to King Solomon and overtly alludes to Aelia Eudocia, Juliana's great-grandmother, who founded this church:

Eudocia the empress, eager to honor God, first built here a temple of Polyektos the servant of God. But she did not make it as great and beautiful as it is... because her prophetic soul told her that she would leave a family well knowing how to adorn it. Whence Juliana, the glory of her blessed parents, inheriting their royal blood in the fourth generation, did not disappoint the hopes of the empress, the mother of a noble race, but raised this from a small temple to its present size and beauty. (Greek Anthology, I.10)

See also

References

- Maas, Michael. The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian. Cambridge University Press, 2005. Page 439.

- Natalie Harris Bluestone, Double Vision: Perspectives on Gender and the Visual Arts (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1995), p. 76 ISBN 0-8386-3540-7

- G.W. Bowersock, Oleg Grabar, Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World (Harvard University Press, 1999), pp. 300-301

- Kiilerich, Bente (2001-01-01). "The Image of Anicia Juliana in the Vienna Dioscurides: Flattery or Appropriation of Imperial Imagery?". Symbolae Osloenses. 76 (1): 169–190. doi:10.1080/003976701753388012. ISSN 0039-7679. S2CID 161294966.

- Kiilerich, Bente (2001-01-01). "The Image of Anicia Juliana in the Vienna Dioscurides: Flattery or Appropriation of Imperial Imagery?". Symbolae Osloenses. 76 (1): 169–190. doi:10.1080/003976701753388012. ISSN 0039-7679. S2CID 161294966.

- Spatharakis, Iohannis (1976). The Portrait in Byzantine Illuminated Manuscripts. Byzantina Neerlandica 6. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 147. ISBN 9004047832.

- The Cambridge Ancient History, 1925. Page 70.