Amir Khusrau

Abu'l Hasan Yamīn ud-Dīn Khusrau (1253–1325 AD), better known as Amīr Khusrau Dehlavī, was an Indian Sufi singer, poet and scholar who lived under the Delhi Sultanate. He was an iconic figure in the cultural history of the Indian subcontinent. He was a mystic and a spiritual disciple of Nizamuddin Auliya of Delhi, India. He wrote poetry primarily in Persian, but also in Hindavi. A vocabulary in verse, the Ḳhāliq Bārī, containing Arabic, Persian, and Hindavi terms is often attributed to him.[1] Khusrau is sometimes referred to as the "voice of India" or "Parrot of India" (Tuti-e-Hind), and has been called the "father of Urdu literature."[2][3][4][5]

Aamir Khusrau | |

|---|---|

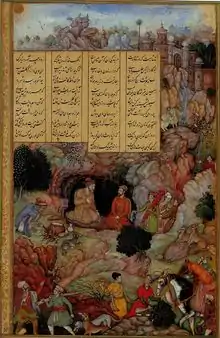

Amir Khusrow teaching his disciples in a miniature from a manuscript of Majlis al-Ushshaq by Husayn Bayqarah. | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Ab'ul Hasan Yamīn ud-Dīn K͟husrau |

| Born | 1253 Patiyali, Delhi Sultanate (now in Uttar Pradesh, India) |

| Died | October 1325 (aged 71–72) Delhi, Delhi Sultanate |

| Genres | Ghazal, Qawwali, Ruba'i, Tarana |

| Occupation(s) | Sufi, singer, poet, composer, author, scholar |

| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

|

|

Khusrau is regarded as the "father of qawwali" (a devotional form of singing of the Sufis in the Indian subcontinent), and introduced the ghazal style of song into India, both of which still exist widely in India and Pakistan.[6][7] Khusrau was an expert in many styles of Persian poetry which were developed in medieval Persia, from Khāqānī's qasidas to Nizami's khamsa. He used 11 metrical schemes with 35 distinct divisions. He wrote in many verse forms including ghazal, masnavi, qata, rubai, do-baiti and tarkib-band. His contribution to the development of the ghazal was significant.[8]

Family background

Amīr Khusrau was born in 1253 in Patiyali, Kasganj district, in modern-day Uttar Pradesh, India, in what was then the Delhi Sultanate, the son of Amīr Saif ud-Dīn Mahmūd, a man of Turkic extraction and Bibi Daulat Naz, a native Hindustani mother. Amir Khusrau was a Sunni Muslim. Amīr Saif ud-Dīn Mahmūd was born a member of the Lachin tribe of Transoxania, themselves belonging to the Kara-Khitai set of Turkic tribes.[8][9][10] He grew up in Kesh, a small town near Samarkand in what is now Uzbekistan. When he was a young man, the region was despoiled and ravaged by Genghis Khan's invasion of Central Asia, and much of the population fled to other lands, India being a favored destination. A group of families, including that of Amir Saif ud-Din, left Kesh and travelled to Balkh (now in northern Afghanistan), which was a relatively safe place; from here, they sent representations to the Sultan of distant Delhi seeking refuge and succour. This was granted, and the group then travelled to Delhi. Sultan Shams ud-Din Iltutmish, ruler of Delhi, was himself a Turk like them; indeed, he had grown up in the same region of Central Asia and had undergone somewhat similar circumstances in earlier life. This was the reason the group had turned to him in the first place. Iltutmish not only welcomed the refugees to his court but also granted high offices and landed estates to some of them. In 1230, Amir Saif ud-Din was granted a fief in the district of Patiyali.

Amir Saif ud-Din married Bibi Daulat Naz, the daughter of Rawat Arz, an Indian noble and war minister of Ghiyas ud-Din Balban, the ninth Sultan of Delhi. Daulatnaz's family belonged to the Rajput community of modern-day Uttar Pradesh.[10][11]

Early years

Amir Saif ud-Din and Bibi Daulatnaz became the parents of four children: three sons (one of whom was Khusrau) and a daughter. Amir Saif ud-Din Mahmud died in 1260, when Khusrau was only eight years old.[12]:2 Through his father's influence, he imbibed Islam and Sufism coupled with proficiency in Turkish, Persian, and Arabic languages.[12]:2 Over and over again in his poetry, and throughout his life, he affirmed that he was an Indian Turk (Turk-e-Hindustani).[13] Khusrau's love and admiration for his motherland is transparent through his work. Persian lyricist Hafiz of Shirazulla described him as Tooti-e-Hind - the singing bird of India.[12]:3

Khusrau was an intelligent child. He started learning and writing poetry at the age of nine.[12]:3 His first divan, Tuhfat us-Sighr (The Gift of Childhood), containing poems composed between the ages of 16 and 18, was compiled in 1271. In 1273, when Khusrau was 20 years old, his grandfather, who was reportedly 113 years old, died.

Career

After Khusrau's grandfather's death, Khusrau joined the army of Malik Chajju, a nephew of the reigning Sultan, Ghiyas ud-Din Balban. This brought his poetry to the attention of the Assembly of the Royal Court where he was honored.

Nasir ud-Din Bughra Khan, the second son of Balban, was invited to listen to Khusrau. He was impressed and became Khusrau's patron in 1276. In 1277 Bughra Khan was then appointed ruler of Bengal, and Khusrau visited him in 1279 while writing his second divan, Wast ul-Hayat (The Middle of Life). Khusrau then returned to Delhi. Balban's eldest son, Khan Muhammad (who was in Multan), arrived in Delhi, and when he heard about Khusrau he invited him to his court. Khusrau then accompanied him to Multan in 1281. Multan at the time was the gateway to India and was a center of knowledge and learning. Caravans of scholars, tradesmen and emissaries transited through Multan from Baghdad, Arabia and Persia on their way to Delhi. Khusrau wrote that:

I tied the belt of service on my waist and put on the cap of companionship for another five years. I imparted lustre to the water of Multan from the ocean of my wits and pleasantries.

On 9 March 1285, Khan Muhammad was killed in battle while fighting Mongols who were invading the Sultanate. Khusrau wrote two elegies in grief of his death. In 1287, Khusrau travelled to Awadh with another of his patrons, Amir Ali Hatim. At the age of eighty, Balban called his second son Bughra Khan back from Bengal, but Bughra Khan refused. After Balban's death in 1287, his grandson Muiz ud-Din Qaiqabad, Bughra Khan's son, was made the Sultan of Delhi at the age of 17. Khusrau remained in Qaiqabad's service for two years, from 1287 to 1288. In 1288 Khusrau finished his first masnavi, Qiran us-Sa'dain (Meeting of the Two Auspicious Stars), which was about Bughra Khan meeting his son Muiz ud-Din Qaiqabad after a long enmity. After Qaiqabad suffered a stroke in 1290, nobles appointed his three-year-old son Shams ud-Din Kayumars as Sultan. A Turko-Afghan named Jalal ud-Din Firuz Khalji then marched on Delhi, killed Qaiqabad and became Sultan, thus ending the Mamluk dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate and starting the Khalji dynasty.

Jalal ud-Din Firuz Khalji appreciated poetry and invited many poets to his court. Khusrau was honoured and respected in his court and was given the title "Amir". He was given the job of "Mushaf-dar". Court life made Khusrau focus more on his literary works. Khusrau's ghazals which he composed in quick succession were set to music and were sung by singing girls every night before the Sultan. Khusrau writes about Jalal ud-Din Firuz:

The King of the world Jalal ud-Din, in reward for my infinite pain which I undertook in composing verses, bestowed upon me an unimaginable treasure of wealth.

In 1290 Khusrau completed his second masnavi, Miftah ul-Futuh (Key to the Victories), in praise of Jalal ud-Din Firuz's victories. In 1294 Khusrau completed his third divan, Ghurrat ul-Kamaal (The Prime of Perfection), which consisted of poems composed between the ages of 34 and 41.

After Jalal ud-Din Firuz, Ala ud-Din Khalji ascended to the throne of Delhi in 1296. Khusrau wrote the Khaza'in ul-Futuh (The Treasures of Victory) recording Ala ud-Din's construction works, wars and administrative services. He then composed a khamsa (quintet) with five masnavis, known as Khamsa-e-Khusrau (Khamsa of Khusrau), completing it in 1298. The khamsa emulated that of the earlier poet of Persian epics, Nizami Ganjavi. The first masnavi in the khamsa was Matla ul-Anwar (Rising Place of Lights) consisting of 3310 verses (completed in 15 days) with ethical and Sufi themes. The second masnavi, Khusrau-Shirin, consisted of 4000 verses. The third masnavi, Laila-Majnun, was a romance. The fourth voluminous masnavi was Aina-e-Sikandari, which narrated the heroic deeds of Alexander the Great in 4500 verses. The fifth masnavi was Hasht-Bihisht, which was based on legends about Bahram V, the fifteenth king of the Sasanian Empire. All these works made Khusrau a leading luminary in the world of poetry. Ala ud-Din Khalji was highly pleased with his work and rewarded him handsomely. When Ala ud-Din's son and future successor Qutb ud-Din Mubarak Shah Khalji was born, Khusrau prepared the horoscope of Mubarak Shah Khalji in which certain predictions were made. This horoscope is included in the masnavi Saqiana.[15]

In 1300, when Khusrau was 47 years old, his mother and brother died. He wrote these lines in their honour:

A double radiance left my star this year

Gone are my brother and my mother,

My two full moons have set and ceased to shine

In one short week through this ill-luck of mine.

Khusrau's homage to his mother on her death was:

Where ever the dust of your feet is found is like a relic of paradise for me.

In 1310 Khusrau became a disciple of Sufi saint of the Chishti Order, Nizamuddin Auliya.[12]:2 In 1315, Khusrau completed the romantic masnavi Duval Rani - Khizr Khan (Duval Rani and Khizr Khan), about the marriage of the Vaghela princess Duval Rani to Khizr Khan, one of Ala ud-Din Khalji's sons.

After Ala ud-Din Khalji's death in 1316, his son Qutb ud-Din Mubarak Shah Khalji became the Sultan of Delhi. Khusrau wrote a masnavi on Mubarak Shah Khalji called Nuh Sipihr (Nine Skies), which described the events of Mubarak Shah Khalji's reign. He classified his poetry in nine chapters, each part of which is considered a "sky". In the third chapter he wrote a vivid account of India and its environment, seasons, flora and fauna, cultures, scholars, etc. He wrote another book during Mubarak Shah Khalji's reign by name of Ijaz-e-Khusravi (The Miracles of Khusrau), which consisted of five volumes. In 1317 Khusrau compiled Baqia-Naqia (Remnants of Purity). In 1319 he wrote Afzal ul-Fawaid (Greatest of Blessings), a work of prose that contained the teachings of Nizamuddin Auliya.

In 1320 Mubarak Shah Khalji was killed by Khusro Khan, who thus ended the Khalji dynasty and briefly became Sultan of Delhi. Within the same year, Khusro Khan was captured and beheaded by Ghiyath al-Din Tughlaq, who became Sultan and thus began the Tughlaq dynasty. In 1321 Khusrau began to write a historic masnavi named Tughlaq Nama (Book of the Tughlaqs) about the reign of Ghiyath al-Din Tughlaq and that of other Tughlaq rulers.

Khusrau died in October 1325, six months after the death of Nizamuddin Auliya. Khusrau's tomb is next to that of his spiritual master in the Nizamuddin Dargah in Delhi.[16] Nihayat ul-Kamaal (The Zenith of Perfection) was compiled probably a few weeks before his death.

Shalimar Bagh Inscription

A popular fable which has made its way into scholarship ascribes the following famous Persian verse to Khusrau:

Agar Firdaus bar ru-ye zamin ast,

Hamin ast o hamin ast o hamin ast.

In English: "If there is a paradise on earth, it is this, it is this, it is this."[17][18][19] This verse is believed to have been inscribed on several Mughal structures, supposedly in reference to Kashmir, specifically a particular building at the Shalimar Garden in Srinagar, Kashmir (built during the reign of Mughal Emperor Jahangir).[20][21]

However, recent scholarship has traced the verse to a time much later than that of Khusrau and to a place quite distant from Kashmir.[22] Historian Rana Safvi inspected all probable buildings in the Kashmir garden and found no such inscription attributed to Khusrau. According to her the verse was composed by Sa’adullah Khan, a leading noble and scholar in the court of Jahangir’s successor and son Shah Jahan.[22] Even in popular memory, it was Jahangir who first repeated the phrase in praise of Kashmir [19]

Contributions to Hindustani Music

Qawwali

Khusrau is credited with fusing the Persian, Arabic, Turkic, and Indian singing traditions in the late 13th century to create qawwali, a form of Sufi devotional song.[23] A well-punctuated chorus emphasizing the theme and devotional refrain coupled with a lead singer utilizing an ornate style of fast taans and difficult svara combinations are the distinguishing characteristics of a qawwali.[12]:4 Khusrau's disciples who specialized in Qawwali singing were later classified as Qawwals (they sang only Muslim devotional songs) and Kalawants (they sang mundane songs in the Qawwali style).[12]:4

Tarana and Trivat

Tarana and Trivat are also credited to Khusrau.[12]:5 Musicologist and philosopher Jaidev Singh has said:

[Tarana] was entirely an invention of Khusrau. Tarana is a Persian word meaning a song. Tillana is a corrupt form of this word. True, Khusrau had before him the example of Nirgit songs using śuṣk-akṣaras (meaningless words) and pāṭ-akṣaras (mnemonic syllables of the mridang). Such songs were in vogue at least from the time of Bharat. But generally speaking, the Nirgit used hard consonants. Khusrau introduced two innovations in this form of vocal music. Firstly, he introduced mostly Persian words with soft consonants. Secondly, he so arranged these words that they bore some sense. He also introduced a few Hindi words to complete the sense…. It was only Khusrau’s genius that could arrange these words in such a way to yield some meaning. Composers after him could not succeed in doing so, and the tarana became as meaningless as the ancient Nirgit.[24]

It is believed that Khusrau invented the tarana style during his attempt to reproduce Gopal Naik's exposition in raag Kadambak. Khusrau hid and listened to Gopal Naik for six days, and on the seventh day, he reproduced Naik's rendition using meaningless words (mridang bols) thus creating the tarana style.[12]:5

Modern scholars, however, are quick to dismiss this story as an urban legend. One reason for this is that the Raga Kadambak is such a complex composition that assimilating its intricacies merely by listening is virtually impossible.

Legacy

Amir Khusrau was a prolific classical poet associated with the royal courts of more than seven rulers of the Delhi Sultanate. He wrote many playful riddles, songs and legends which have become a part of popular culture in South Asia. His riddles are one of the most popular forms of Hindavi poetry today.[25] It is a genre that involves double entendre or wordplay.[25] Innumerable riddles by the poet have been passed through oral tradition over the last seven centuries.[25] Through his literary output, Khusrau represents one of the first recorded Indian personages with a true multicultural or pluralistic identity. Musicians credit Khusrau with the creation of six styles of music: qaul, qalbana, naqsh, gul, tarana and khyal, but there is insufficient evidence for this.[26][27]

Development of Hindavi

Khusrau wrote primarily in Persian. Many Hindustani (historically known as Hindavi) verses are attributed to him, since there is no evidence for their composition by Khusrau before the 18th century.[28][29] The language of the Hindustani verses appears to be relatively modern. He also wrote a war ballad in Punjabi.[30] In addition, he spoke Arabic and Sanskrit.[10][31][32][33][34][35][36] His poetry is still sung today at Sufi shrines throughout India and Pakistan.

In popular culture

The 1978 film Junoon opens with a rendition of Khusrau's Aaj Rung Hai, and the film's plot sees the poem employed as a symbol of rebellion.[37]

Amir Khusro an Indian television series based on Khusrau's life and works aired on DD National, the national public broadcaster, in the 1980s.[38][39]

One of Khusro's poems on Basant, Sakal bun phool rahi sarson, was quoted in an issue of Saladin Ahmed's The Magnificent Ms. Marvel. The inclusion of the poem - used to illustrate a pivotal moment in the comic - drew praise on social media.[40][41]

On the 25th December, 2020 Pakistani singer Meesha Shafi and the instrumental funk band Mughal-e-Funk collaborated and released a rendition of the poem. [42]

Works

- Tuhfat us-Sighr (The Gift of Childhood), 1271 - Khusrau's first divan, contains poems composed between the ages of 16 and 18.

- Wast ul-Hayat (The Middle of Life), 1279 - Khusrau's second divan.

- Qiran us-Sa’dain (Meeting of the Two Auspicious Stars), 1289 - Khusrau's first masnavi, which detailed the historic meeting of Bughra Khan and his son Muiz ud-Din Qaiqabad after a long enmity.

- Miftah ul-Futuh (Key to the Victories), 1290 - Khusrau's second masnavi, in praise of the victories of Jalal ud-Din Firuz Khalji.

- Ghurrat ul-Kamaal (The Prime of Perfection), 1294 - poems composed by Khusrau between the ages of 34 and 41.

- Khaza'in ul-Futuh (The Treasures of Victories), 1296 - details of Ala ud-Din Khalji's construction works, wars, and administrative services.

- Khamsa-e-Khusrau (Khamsa of Khusrau), 1298 - a quintet (khamsa) of five masnavis: Matla ul-Anwar, Khusrau-Shirin, Laila-Majnun, Aina-e-Sikandari and Hasht-Bihisht.

- Saqiana - masnavi containing the horoscope of Qutb ud-Din Mubarak Shah Khalji.

- Duval Rani - Khizr Khan (Duval Rani and Khizr Khan), 1316 - a tragedy about the marriage of princess Duval Rani to Ala ud-Din Khalji's son Khizr Khan.

- Nuh Sipihr (Nine Skies), 1318 - Khusrau's masnavi on the reign of Qutb ud-Din Mubarak Shah Khalji, which includes vivid perceptions of India and its culture.

- Ijaz-e-Khusravi (The Miracles of Khusrau) - an assortment of prose consisting of five volumes.

- Baqia-Naqia (Remnants of Purity), 1317 - compiled by Khusrau at the age of 64.

- Afzal ul-Fawaid (Greatest of Blessings), 1319 - a work of prose containing the teachings of Nizamuddin Auliya.

- Tughlaq Nama (Book of the Tughlaqs), 1320 - a historic masnavi of the reign of the Tughlaq dynasty.

_of_Amir_Khusrau_Dihlavi.jpg.webp) "A King Offers to Make Amends to a Bereaved Mother" is a painting based on a story written by Amir Khusrau Dihlavi, but illustrated by Mughal Indian artist, Miskin, in 1597-98.

"A King Offers to Make Amends to a Bereaved Mother" is a painting based on a story written by Amir Khusrau Dihlavi, but illustrated by Mughal Indian artist, Miskin, in 1597-98. - Nihayat ul-Kamaal (The Zenith of Perfection), 1325 - compiled by Khusrau probably a few weeks before his death.

- Ashiqa - Khusro pays a glowing tribute to Hindi language and speaks of its rich qualities.[43] It is a masnavi that describes the tragedy of Deval Devi. The story has been backed by Isaami.[44]

- Qissa Chahar Dervesh (The Tale of the Four Dervishes) - a dastan told by Khusrau to Nizamuddin Auliya.

- Ḳhāliq Bārī - a versified glossary of Persian, Arabic, and Hindavi words and phrases often attributed to Amir Khusrau. Hafiz Mehmood Khan Shirani argued that it was completed in 1622 in Gwalior by Ẓiyā ud-Dīn Ḳhusrau.[45]

- Jawahir-e-Khusravi - a divan often dubbed as Khusrau's Hindavi divan.

References

- Rashid, Omar (23 July 2012). "Chasing Khusro". Chennai, India: The Hindu. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- "Amīr Khosrow - Indian poet".

- Jaswant Lal Mehta (1980). Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India. 1. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 10. ISBN 9788120706170.

- Bakshi, Shiri Ram; Mittra, Sangh (2002). Hazart Nizam-Ud-Din Auliya and Hazrat Khwaja Muinuddin Chisti. Criterion.

- Bhattacharya, Vivek Ranjan (1982). Famous Indian sages: their immortal messages. Sagar Publications.

- Latif, Syed Abdulla (1979) [1958]. An Outline of the Cultural History of India. Institute of Indo-Middle East Cultural Studies (reprinted by Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers). p. 334. ISBN 81-7069-085-4.

- Regula Burckhardt Qureshi, Harold S. Powers. Sufi Music of India. Sound, Context and Meaning in Qawwali. Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 109, No. 4 (Oct. – Dec. 1989), pp. 702–705. doi:10.2307/604123.

- Schimmel, A. "Amīr Ḵosrow Dehlavī". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Eisenbrauns Inc. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- "Амир Хосров Дехлеви", Great Soviet Encyclopedia, Moscow, 1970 Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Central Asia and Iran". angelfire.com.

- Asad, Muhammad (16 February 2018). "Islamic Culture". Islamic Culture Board – via Google Books.

- Misra, Susheela (1981). Great Masters of Hindustani Music. New Delhi: Hem Publishers Pvt Ltd.

- Khilnani, Sunil (2016), Incarnations: India in 50 Lives, Penguin Books Limited, p. 108, ISBN 978-0-241-20823-6

- "Alexander is Lowered into the Sea". metmuseum.org. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- "Hazrat Mehboob-E-Elahi (RA)". hazratmehboob-e-elahi.org.

- Nizamuddin Auliya

- Rajan, Anjana (29 April 2011). "Window to Persia". The Hindu. Chennai, India.

- "Zubin Mehta's concert mesmerises Kashmir". Press Trust of India. 7 September 2013 – via Business Standard.

- "Zubin Mehta's concert mesmerizes Kashmir - The Times of India". The Times Of India.

- "Shalimar Garden | District Srinagar, Government of Jammu and Kashmir | India". Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- Blake, Stephen P. (30 April 2002). Shahjahanabad: The Sovereign City in Mughal India 1639-1739. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521522991 – via Google Books.

- Safvi, Rana. "Who really wrote the lines 'If there is Paradise on earth, it is this, it is this, it is this'?". Scroll.in. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- "'Aaj rang hai' - Qawwali revisited". TwoCircle.net. Retrieved 8 March 2013., Retrieved 16 September 2015

- Singh, Thakur Jai Deva (1975). "Khusrau's Musical Compositions". In Ansari, Zoe (ed.). Life, Times & Works of Amir Khusrau Dehlavi. New Delhi: National Amir Khusrau Society. p. 276.

- Sharma, Sunil (2005). Amir Khusraw : the poet of Sufis and sultans. Oxford: Oneworld. p. 79. ISBN 1851683623.

- "Amir Khusrau and the Indo-Muslim Identity in the Art Music Practices of Pakistan".

- "Amir Khusro and his influence on Indian classical music".

- Losensky, Paul E. (15 July 2013). In the Bazaar of Love: The Selected Poetry of Amir Khusrau. Penguin UK. ISBN 9788184755220 – via Google Books.

- Khusrau's Hindvi Poetry, An Academic Riddle? Yousuf Saeed, 2003

- Tariq, Rahman. "Punjabi Language during British Rule" (PDF). JPS. 14 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2012.

- Habib, Mohammad (16 February 2018). "Hazrat Amir Khusrau of Delhi". Islamic Book Service – via Google Books.

- Asad, Muhammad (16 February 2018). "Islamic Culture". Islamic Culture Board – via Google Books.

- Dihlavī, Amīr Khusraw (16 February 1975). "Amir Khusrau: Memorial Volume". Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India – via Google Books.

- Dihlavī, Amīr Khusraw (16 February 1975). "Amir Khusrau: Memorial Volume". Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India – via Google Books.

- Devy, G. N. (16 February 2018). Indian Literary Criticism: Theory and Interpretation. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 9788125020226 – via Google Books.

- Dihlavī, Amīr Khusraw (16 February 1975). "Amir Khusrau: Memorial Volume". Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India – via Google Books.

- "How Amir Khusrau's 'rung' inspired the film and music culture of South Asia". Firstpost. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Rahman, M. (15 June 1988). "Rajbans Khanna's TV serial Amir Khusrau attempts to clear communal misconceptions". India Today.

- "Amir Khusro". nettv4u.

- "Ms Marvel Comic Pays Tribute to Amir Khusro's Poetry and People Are Losing Their Minds". Lens. 4 February 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "Muslim, Immigrant, Teenager...Superhero: How Ms. Marvel Will Save the World". Religion Dispatches. 14 March 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "Sakal Ban by Mughal-E-Funk feat. Meesha Shafi (Official Video) - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20190720175230/https://www.freepressjournal.in/mind-matters/the-mystic-poet#bypass-sw

- The Life and Works of Sultan Alauddin Khalji. Delhi: Atlantic. 1992. p. 5. ISBN 8171563627.

- Shīrānī, Ḥāfiż Mahmūd. "Dībācha-ye duvum [Second Preface]." In Ḥifż ’al-Lisān (a.k.a. Ḳhāliq Bārī), edited by Ḥāfiż Mahmūd Shīrānī. Delhi: Anjumman-e Taraqqi-e Urdū, 1944.

Further reading

- Sharma, Sunil (2017). "Amīr Khusraw Dihlavī". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- E.G. Browne. Literary History of Persia. (Four volumes, 2,256 pages, and twenty-five years in the writing). 1998. ISBN 0-7007-0406-X

- Jan Rypka, History of Iranian Literature. Reidel Publishing Company. ASIN B-000-6BXVT-K

- R.M. Chopra, "The Rise, Growth And Decline of Indo-Persian Literature", Iran Culture House New Delhi and Iran Society, Kolkata, 2nd Ed. 2013.

- Sunil Sharma, Amir Khusraw: Poets of Sultans and Sufis. Oxford: Oneworld Press, 2005.

- Paul Losensky and Sunil Sharma, In the Bazaar of Love: Selected Poetry of Amir Khusrau. New Delhi: Penguin, 2011.

- R.M. Chopra, "Great Poets of Classical Persian", Sparrow Publication, Kolkata, 2014, ISBN 978-81-89140-75-5

- Zoe, Ansari, "Khusrau ka Zehni Safar", Anjuman Taraqqī-yi-Urdū, New Delhi, 1988.

- Important Works of Amir Khusrau (Complete)

- The Khaza'inul Futuh (Treasures of Victory) of Hazarat Amir Khusrau of Delhi English Translation by Muhammad Habib (AMU). 1931.

- Poems of Amir Khusrau The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians: The Muhammadan Period, by Sir H. M. Elliot. Vol III. 1866-177. page 523-566.

- Táríkh-i 'Aláí; or, Khazáínu-l Futúh, of Amír Khusrú The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians: The Muhammadan Period, by Sir H. M. Elliot. Vol III. 1866-177. Page:67-92.

- For greater details refer to "Great Poets of Classical Persian" by R. M. Chopra, Sparrow Publication, Kolkata, 2014, (ISBN 978-81-89140-75-5)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amir Khusrow. |

- Works by Amir Khusrau at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Amir Khusrau at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Original Persian poems of Amir Khusrau at WikiDorj, free library of Persian poetry

- "A King Offers to Make Amends to a Bereaved Mother", Folio from a Khamsa (Quintet) of Amir Khusrau Dihlavi. The Metropolitan Museum of Art