American Astronomical Society 215th meeting

The 215th meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) took place in Washington, D.C., Jan. 3 to Jan. 7, 2010. It is one of the largest astronomy meetings ever to take place as 3,500 astronomers and researchers were expected to attend and give more than 2,200 scientific presentations. The meeting was actually billed as the "largest Astronomy meeting in the universe". An array of discoveries were announced, along with new views of the universe that we inhabit; such as quiet planets like Earth - where life could develop are probably plentiful, even though an abundance of cosmic hurdles exist - such as experienced by our own planet in the past.[1][2][3]

Infrared scanning the sky

The NASA mission of the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) is to use infrared light to scan the entire sky for millions of hidden objects, including asteroids, failed stars and powerful galaxies . Launched on December 14, 2009, the data from WISE will serve as a navigation tool for other probes in space missions, such as NASA's Hubble telescope and the Spitzer Space Telescope. The first image was presented at the 215th annual AAS meeting. An infrared snapshot of a region in the constellation Carina, near the Milky Way was taken shortly after the survey telescope ejected its cover. In a patch of sky three times larger than the moon, the picture shows about 3,000 stars in the Carina constellation.[1]

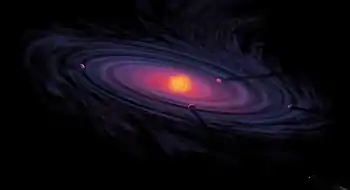

Planet formation around massive Stars

The focus for discovering new exoplanets has been on sun-like stars. The catalog of more than 400 exoplanets has proved that these searches are successful, because exoplanets of various sizes have been discovered. However, other star types are also a likely place to discover new exoplanets. New research, announced at the meeting, confirms that planet formation is a natural by-product of star formation. Planet formation occurs even around stars much more massive than the Sun. However, the life of the stars which the planets orbit are so short that intelligent extraterrestrial life is not very likely. A and B type stars were surveyed for the research which involved NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, the Two Micron All-Sky Survey, and astronomers from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) and the National Optical Astronomy Observatory (NOAO).[1][4]

Gravitational wave detection

In a span of three months seventeen pulsars - millisecond pulsars - were discovered in the Milky Way galaxy. Unknown high-energy sources detected by NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope revealed the existence and location of the pulsars. This is an accelerated pace for discovering such objects, which could be used as a "galactic GPS" to detect gravitational waves passing near Earth. Although the pulsars are relatively old they have not slowed because, these millisecond pulsars have been kept rapidly rotating and renewed with material by accretion of matter from a companion star. The combined total of 60 known millisecond pulsars creates an all-sky array. Precise monitoring of timing changes, utilizing this array, may allow the first direct detection of gravitational waves.[1]

Temperature, gravity, and planet migration

According to the classical model of planet migration, the earth should have been drawn into the sun as a planetoid, along with other planets. However, a new theoretical model was presented at the annual meeting. It shows that the assumption a proto-planetary disk around a star has constant temperature across its whole span is erroneous. Portions of the disk are actually opaque and so cannot cool quickly by radiating heat out to space. This creates temperature differences across the disk, and these differences have not been accounted for before in models that were applied. The differences in temperature counteract the natural gravitational pull of the sun (or proto-sun), at a crucial time during planet formation.

Kepler space telescope

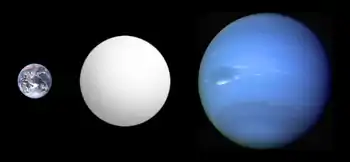

On 4 January 2010, the Kepler space telescope announced the discovery its first five new exoplanets, named Kepler-4b, 5b, 6b, 7b and 8b.[5] These exoplanets had sizes comparable to that of Neptune to larger than Jupiter, with orbits ranging from 3.3 to 4.9 days, and estimated temperatures ranging from 2,200 °F to 3,000 °F (1,200 °C to 1,650 °C).

Super-earth HD156668b

The discovery of HD156668b, a super-earth class exoplanet, was announced on January 7, 2010, at the 215th meeting American Astronomical Society (AAS), in Washington DC.[6]

Overview

A super-Earth is an extrasolar planet with a mass between that of Earth and the Solar System's gas giants. The term super-Earth refers only to the mass of the planet and does not imply anything about the surface conditions or habitability.[7]

Andrew Howard of the University of California at Berkeley, announced the planet's discovery at the 215th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Washington, D.C.

At the meeting, the details of the findings were first presented by the research group which had used the twin Keck Telescopes in Hawaii to detect the exoplanet. With the twin telescopes functioning as a single observatory, by means of interferometry, it was determined that HD156668b is only four times larger than the Earth, and the second smallest exoplanet yet found.[6]

There are over 400 exoplanets thus far discovered, and only a very small number are categorized as Super-earth class. Finding such planets as HD156668b, which are closer to earth in size, has become a priority in Astronomy science. For example, the Kepler mission, is part of the intense popular interest surrounding the discovery of hundreds of planets orbiting other stars. Kepler telescope, however has a more specific mission - to discover hundreds of terrestrial planets which are defined as exoplanets that are one half to twice the size of the Earth.[6][8]

A priority is to find those in the habitable zone of their stars where liquid water and possibly life might exist. Discoveries such as HD156668b allow astronomers such as the Keck research group to demonstrate they are able to find smaller and smaller planets. Ultimately, results such as those from the Keck group, and the Keppler mission will allow the Solar System to be placed within a continuum of planetary systems in the Galaxy.[6][8]

HD156668b, is considered to be relatively close at just 80 light-years away. It is in the constellation Hercules. According to early measurements, it appears to be orbiting its parent star about once every four days (approximately). The wobble of the planet's star revealed the existence of HD156668b. The alignment probability is 0.5% for finding a planet in an Earth-like orbit about a solar-like star, compared to the giant planets discovered in four-day orbits, the alignment probability is more like 10%.[6][8]

Other researchers from the California Institute of Technology, Yale University and Penn State University also participated in the study.[9]

Black hole update

Black holes along with new data were a notable topic at the conference.

Black hole pairs

Almost every galaxy has a black hole with a mass of one million to one billion times that of the sun. A super-massive black hole, of more than 4 million solar masses, is located in the center of our own Milky Way galaxy. As the universe has evolved, galaxies often collide and merge, creating larger galaxies. This has led to the supposition that galaxies in mid-merge should have a two great black holes (a pair) orbiting one another. Expectations were, that this should be a common observation, hand in hand with mid merge collisions. However, observation has not validated this supposition; only a few orbiting pairs had been found. When observation did not match expectation, this posed problems for theories of how galaxies merge and grow.[10][11]

These statistics have been recently altered. 33 pair of super-massive orbiting black holes were recently discovered. The first 32 pair by the DEEP2 Galaxy Redshift Survey conducted with the Keck II Telescope on Hawaii's Mauna Kea. This survey determined which black hole was moving toward earth at which time. When the black hole moves toward Earth, its light is blue-shifted, meaning it has a shorter wavelength. Orbiting pairs were identified by looking for instances when one black hole was blueshifted and the other redshifted. The pairs orbit each other at 200 km per second, at several thousand light years apart.[10][11]

Intermediate mass black hole

In a globular cluster 65 million light years from Earth evidence is accumulating that a black hole, one thousand times more massive than the sun, has caused the destruction of a white dwarf star. It appears that the white dwarf is heating up as it falls toward the black hole. This event creates an intense stellar astrophysical X-ray source, called an ultraluminous X-ray source. The indication of this type of strong X-ray source means that it is more luminous than any known stellar X-ray source, but less luminous than the X-ray intensity of supermassive black holes, which places it in the range of theorized intermediate black holes. Their exact nature of ULXs has remained a mystery, but one suggestion is that some ULXs are black holes with masses between about a hundred and a thousands times that of the Sun.[12][13][14]

A mix of detected natural elements seems to indicate the actual source of the X-ray emissions are debris from the white dwarf. If evidence authenticates the observations from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and the Magellan telescopes, it means the first actual observation of an intermediate black hole. Furthermore, it would be the first confirmed observation of a black hole destroying a star. And it would support theories which state intermediate black holes exist in globular clusters.[12][13]

Prior to this it has been argued that supermassive black holes in the centers of galaxies are to be attributed with disruption and destruction of stars. However, observing such an event in a globular cluster is a first. To date no candidate for an intermediate black hole has been widely accepted.[12][13]

A possible candidate

Data obtained in optical light with the Magellan I and II telescopes in Las Campanas, Chile, also provides intriguing information about this object, which is found in the elliptical galaxy NGC 1399 in the Fornax galaxy cluster. The spectrum reveals emission from oxygen and nitrogen but no hydrogen, a rare set of signals from within globular clusters. The physical conditions deduced from the spectra suggest that the gas is orbiting a black hole of at least 1,000 solar masses.[14]

To explain these observations, researchers suggest that a white dwarf star strayed too close to an intermediate-mass black hole and was ripped apart by tidal forces. The black hole is swallowing material from the white dwarf star, and the material's velocity implies the size of the black hole. In this scenario the X-ray emission is produced by debris from the disrupted white dwarf star that is heated as it falls towards the black hole and the optical emission comes from debris further out that is illuminated by these X-rays.[14]

Another interesting aspect of this object is that it is found within a globular cluster, a very old, very tight grouping of stars. Astronomers have long suspected globular clusters contained intermediate-mass black holes, but there has been no conclusive evidence of their existence there to date. If confirmed, this finding would represent the first such substantiation.[14]

Galactic Dark Matter Halo

The Milky Way, and probably most other galaxies too, are surrounded by a halo of dark matter. The shape of the Milky Way has been determined. The research is the first time scientists have measured the three-dimensional shape of a dark matter halo .

Other milestones

This section will be expanded.

If a massive white dwarf star explodes millions of years from now it could threaten the earth.

The Hubble Space Telescope has taken the deepest look into the universe yet, revealing some of the most distant, earliest galaxies to form after the Big Bang.

External links

- 215th meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

- Earth-Like Planets May Abound in the Milky Way. AAAS Science Now. April 2010.

References

- Whatmore, R. (6 January 2010). "NASA Announces AAS Events, Features and News Conferences". NASA. Archived from the original on 2010-01-11. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- "Cosmic Coverage of the 215th AAS Meeting". Space.com. 7 January 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- "Astronomers: We could find Earth-like planets soon". China Daily. 8 January 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- Aguilar, D. A.; Pulliam, C. (6 January 2010). "Massive Stars: Good Targets for Planet Hunts, Bad Targets for SETI". Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Retrieved 2009-01-11.

- "The First Five". NASA/Ames Research Center. 4 January 2010. Retrieved 2014-07-22.

- Vieru, T. (8 January 2010). "Second Smallest Exoplanet Found". Softpedia. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- Valencia, D.; Sasselov, D. D.; O'Connell, R. J. (2007). "Radius and structure models of the first super-Earth planet". The Astrophysical Journal. 656 (1): 545–551. arXiv:astro-ph/0610122. Bibcode:2007ApJ...656..545V. doi:10.1086/509800.

- Borucki, W.; Koch, D. (5 November 2013). "About the Mission". NASA/Ames Research Center. Archived from the original on 8 May 2012. Retrieved 2014-07-22.

- "Distant Planet is Second Smallest Super-Earth". Space.com. 17 January 2010. Retrieved 2014-07-22.

- Grossman, L. (5 January 2010). "Elusive Supermassive-Black-Hole Mergers Finally Found". Wired. Archived from the original on 8 January 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-21.

- Moseman, A. (20 January 2010). "Breaking News on Black Holes: They "Waltz" in Pairs, Rip Stars Apart". Discover. Retrieved 2014-07-22.

- Atkinson, N. (4 January 2010). "Stellar Destruction Could Be from Intermediate Black Hole". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 2010-01-15. Retrieved 2010-01-27.

- "Massive Black Hole Implicated in Stellar Destruction, UA Astronomer's Research Finds" (Press release). University of Alabama. 4 January 2010. Archived from the original on 22 January 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-27.

- "NGC 1399: Massive Black Hole Implicated in Stellar Destruction". Chandra X-ray Observatory. 2 January 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-03-09. Retrieved 2010-03-10.