Alyattes of Lydia

Alyattes (Ancient Greek: Ἀλυάττης Aluáttēs, likely from Lydian Walwates; reigned c. 618–561 BC), sometimes described as Alyattes I, was the fourth king of the Mermnad dynasty in Lydia, the son of Sadyattes and grandson of Ardys. He died after a reign of 57 years and was succeeded by his son Croesus.[2][3] A battle between his forces and those of Cyaxares, king of Media, was interrupted by the solar eclipse of 28 May 585 BC. After this, a truce was agreed and Alyattes married his daughter Aryenis to Astyages, the son of Cyaxares. The alliance preserved Lydia for another generation, during which it enjoyed its most brilliant period.[4] Alyattes continued to wage a war against Miletus for many years but eventually he heeded the Delphic Oracle and rebuilt a temple, dedicated to Athena, which his soldiers had destroyed. He then made peace with Miletus.[5]

| Alyattes of Lydia | |

|---|---|

Coin of Alyattes. Circa 620/10-564/53 BCE.[1] | |

| Lydian King | |

| Reign | c. 618 – c. 561 BCE |

| Predecessor | Sadyattes |

| Successor | Croesus |

| Issue | Croesus |

| Father | Sadyattes |

Alyattes was the first monarch who issued coins, made from electrum (and his successor Croesus was the first to issue gold coins). Alyattes is therefore sometimes mentioned as the originator of coinage, or of currency.[6]

The Greek form Ἀλυάττης is most likely derived from a name with initial digamma, ϝαλυάττης (walwattes), from a Lydian walwet- (Lydian alphabet: 𐤥𐤠𐤩𐤥𐤤𐤯).[7]

Chronology

Dates for the Mermnad kings are uncertain and are based on a computation by J. B. Bury and Russell Meiggs (1975) who estimated c.687–c.652 BC for the reign of Gyges.[9] Herodotus gave reign lengths for Gyges' successors,[2] but there is uncertainty about these as the total exceeds the timespan between 652 (probable death of Gyges, fighting the Cimmerians) and 547/546 (fall of Sardis to Cyrus the Great). Bury and Meiggs concluded that Ardys and Sadyattes reigned through an unspecified period in the second half of the 7th century BC,[10] but they did not propose dates for Alyattes except their assertion that his son Croesus succeeded him in 560 BC. The timespan 560–546 BC for the reign of Croesus is almost certainly accurate.[11]

Life

For several years Alyattes continued the war against the Greek colony of Miletus begun by his father Sadyattes, but was obliged to turn his attention towards the Medes and Babylonians. On 28 May 585 BC, during the Battle of Halys fought against Cyaxares, king of Media, a solar eclipse occurred; hostilities were suspended, peace concluded, and the Halys River was fixed as the boundary between the two kingdoms.[12]

Alyattes drove the Cimmerians from Asia Minor,[13] with the help of war dogs.[14] He further subdued the Carians, and took several Ionian cities, including Smyrna and Colophon. Smyrna was sacked and destroyed with its inhabitants forced to move into the countryside.[12]

He created the first coins in history made from electrum, a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver. The weight of either precious metal could not just be weighed so they contained an imprint that identified the issuer who guaranteed the value of its contents.[15] Today we still use a token currency, where the value is guaranteed by the state and not by the value of the metal used in the coins.[16] Almost all coins used today descended from his invention after the technology passed into Greek usage through Hermodike II - a Greek princess from Cyme who was likely one of his wives (assuming he was referred to a dynastic 'Midas' because of the wealth his coinage amassed and because the electrum was sourced from Midas' famed river Pactolus; she was also likely the mother of Croesus (see croeseid symbolism. He standardised the weight of coins (1 stater = 168 grains of wheat). The coins were produced using an anvil die technique and stamped with a lion's head, the symbol of the Mermnadae.[17]

Tomb

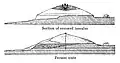

Alyattes' tomb still exists on the plateau between Lake Gygaea and the river Hermus to the north of the Lydian capital Sardis — a large mound of earth with a substructure of huge stones. (38.5723401, 28.0451151) It was excavated by Spiegelthal in 1854, who found that it covered a large vault of finely cut marble blocks approached by a flat-roofed passage of the same stone from the south. The sarcophagus and its contents had been removed by early plunderers of the tomb. All that was left were some broken alabaster vases, pottery and charcoal. On the summit of the mound were large phalli of stone.[12]

Herodotus described the tomb:

But there is one building to be seen there which is more notable than any, saving those of Egypt and Babylon. There is in Lydia the tomb of Alyattes the father of Croesus, the base whereof is made of great stones and the rest of it of mounded earth. It was built by the men of the market and the artificers and the prostitutes. There remained till my time five corner-stones set on the top of the tomb, and on these was graven the record of the work done by each kind: and measurement showed that the prostitutes' share of the work was the greatest.

— Herodotus 1-93.[21]

Some authors have suggested that Buddhist stupas were derived from a wider cultural tradition from the Mediterranean to the Indus valley, and can be related to the funeral conical mounds on circular bases that can be found in Lydia or in Phoenicia from the 8th century BCE, such as the tomb of Alyattes.[22][23][24]

Alyattes tumulus reconstitution

Alyattes tumulus reconstitution Alyattes tomb entrance

Alyattes tomb entrance Alyattes tomb passageway

Alyattes tomb passageway Alyattes tomb inner vault

Alyattes tomb inner vault

Appearance in The Histories

In The Histories, Herodotus recounts how Alyattes continued his father's war against Miletus. According to Herodotus, Sadyattes had invaded Miletus annually to burn their crops over the course of six years. The troops left the horses and houses untouched so that the Milesians could plant a new crop, which the Lydians would then burn the following year. Alyattes did the same over the next five years until the end of the war.[13]

The end came about because of a Lydian fire which, driven out of control by a strong wind, destroyed the temple of Athene at Assesos. Soon afterwards, Alyattes became seriously ill and decided to asked the Delphic Oracle for advice. The priestess refused to answer his emissary until the Lydians had rebuilt the temple. Alyattes immediately sent an embassy to Miletus and agreed a peace treaty. The temple was rebuilt and Alyattes recovered his health.[13]

References

- Weidauer Group XVII, 108 var. Triton XXI (2018) no. 497, auctioned for USD 2750. This particular coin does not bear an inscription, but it is from the same punch as contemporary coins which have the inscription WALWEL. (Classical Numismatics Group).

- Herodotus & de Sélincourt 1954, p. 46

- "Summary of Herodotus | First Floor Tarpley". Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Bury & Meiggs 1975, pp. 142–143

- Bury & Meiggs 1975, p. 143

- A. Ramage, "Golden Sardis", King Croesus' Gold: Excavations at Sardis and the History of Gold Refining, edited by A. Ramage and P. Craddock, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 2000, p. 18.

- Kadmos 34-35 (1995), 51f. The name WALWET is inscribed on some of the coins of the Artemision deposit. Robert W. Wallace, "KUKALIM, WALWET, and the Artemision Deposit: Problems in Early Anatolian Electrum Coinage: Studies in Money and Exchange" in: Peter G. Van Alfen (ed.) Agoranomia: Studies in Money and Exchange Presented to John H. Kroll, American Numismatic Society (2006) 37–49.

- Interpreted as the given name Kukas, equivalent to Gyges, but identification with king Gyges himself is untenable. It is more likely that this "Gyges" was a provincial governor or otherwise in charge of the mint workshop that produced this particular coin. Wallace, “KUKALIṂ”, pl. 1, 1–4 = Weidauer Group XVIII, Triton XV no. 1241 (3 January 2012). Auctioned in 2013 for CHF 25000. (Classical Numismatics Group)

- Bury & Meiggs 1975, pp. 82–83

- Bury & Meiggs 1975, p. 501

- Bury & Meiggs 1975, p. 502

- Chisholm 1911, p. 776

- Herodotus & de Sélincourt 1954, pp. 47–48

- Polyaenus, 7.2

- Harari, Yuval Noah (2015). Sapiens: a Brief History of Humankind. First U.S. Edition: HarperCollins Publishers. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-06-231609-7.

- Amelia Dowler, Curator, British Museum; A History of the World; http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/7cEz771FSeOLptGIElaquA

- Mundall, Robert A. (2002). "The birth of coinage". Columbia Academic Commons. doi:10.7916/D8Q531TK.

- The Tomb of Atyattes (in French). 1993.

- Taylor, Richard P. (2000). Death and the Afterlife: A Cultural Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 381. ISBN 9780874369397.

- Fergusson, James. Rude Stone Monuments. pp. 31–32.

- Herodotus 1-93

- "It is probably traceable to a common cultural inheritance, stretching from the Mediterranean to the Ganges valley, and manifested by the sepulchres, conical mounds of earth on a circular foundation, of about the eighth century B.C. found in Eritrea and Lydia." Rao, P. R. Ramachandra (2002). Amaravati. Youth Advancement, Tourism & Cultural Department Government of Andhra Pradesh. p. 33.

- On the hemispherical Phenician tombs of Amrit: Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. (1972). History of Indian and Indonesian art. p. 12.

- Commenting on Gisbert Combaz: "In his study L'évolution du stupa en Asie, he even observed that "long before India, the classical Orient was inspired by the shape of the tumulus for constructing its tombs: Phrygia, Lydia, Phenicia ." in Bénisti, Mireille; K, Thanikaimony (2003). Stylistics of Buddhist art in India. Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. p. 12. ISBN 9788173052415.

Sources

- Bury, J. B.; Meiggs, Russell (1975) [first published 1900]. A History of Greece (Fourth Edition). London: MacMillan Press. ISBN 0-333-15492-4.

- Herodotus (1975) [first published 1954]. Burn, A. R.; de Sélincourt, Aubrey (eds.). The Histories. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-051260-8.

Attribution:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Alyattes". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 776. This cites A. von Ölfers, "Über die lydischen Königsgräber bei Sardes," Abh. Berl. Ak., 1858.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Alyattes". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 776. This cites A. von Ölfers, "Über die lydischen Königsgräber bei Sardes," Abh. Berl. Ak., 1858.

External links

- Alyattes of Lydia by Jona Lendering

| Preceded by Sadyattes |

King of Lydia c.591–c.560 BC |

Succeeded by Croesus |