Alexander Crum Brown

Alexander Crum Brown FRSE FRS (26 March 1838 – 28 October 1922) was a Scottish organic chemist. Alexander Crum Brown Road in Edinburgh's King's Buildings complex is named after him.

Alexander Crum Brown | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 26 March 1838 |

| Died | 28 October 1922 (aged 84) |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

| Scientific career | |

| Notable students | Acharya Prafulla Chandra Ray |

Early life and education

Born at 4 Bellevue Terrace[1] in Edinburgh, the son of Rev Dr John Brown DD (1784-1858), minister of Broughton Place Church[2] in the east end of Edinburgh's New Town, and Margaret Fisher Crum (d.1841)[3][4] and half brother of the physician and essayist John Brown, he studied for five years at the Royal High School, succeeded by one year at Mill Hill School in London. In 1854 he entered the universities of University of Edinburgh where he first studied Arts and then of Medicine. He was gold medallist in Chemistry and Natural Philosophy and graduated as M.A. in 1858. Continuing his medical studies, he received the degree of M.D. in 1861.[5] During the same time he read for the science degree of University of London, and in 1862 became the first Doctor of Science at the University of London. After his graduation as Doctor of Medicine in Edinburgh he continued the study of chemistry in Germany, first under Robert Bunsen at University of Heidelberg, and then at University of Marburg under Adolph Wilhelm Hermann Kolbe.[6]

Academic career

In 1863 he returned to the University of Edinburgh to accept the position of an extra-academical lecturer in chemistry. In 1865 he became a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, and was appointed Professor of Chemistry at Edinburgh in 1869,[7] holding the Chair until his retirement in 1908. One of his students was Arthur Conan Doyle [8] In the application for this position he was supported by such famous chemists as Baeyer, Beilstein, Bunsen, Butlerov, Erlenmeyer, Hofmann, Kolbe, Volhard and Wöhler.[7] The Crum Brown Chair of Chemistry at the University of Edinburgh was established in 1967 in his honour.[9]

He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1863, was awarded their Keith Medal for 1873-75, and served as their Vice President from 1905 to 1911.[2] His address at the time of joining the Society was given as 8 Belgrave Crescent in the west end of Edinburgh.[10]

The Hope Scholarship controversy of 1870

Each year, the Hope Scholarship was awarded to the four students at the University of Edinburgh who achieved the highest marks (at first sitting) in the first-term examinations in Chemistry. The Hope Scholars were entitled to free use of the laboratory facilities during the following term. In 1870, Edith Pechey, one of the Edinburgh Seven, came third in the class, beaten by two male students sitting the exam for the second time, so under the terms of the Hope Scholarship, she had first claim on it. Fearing that awarding the prize to a woman would be both an affront to many of his esteemed colleagues in the Medical Faculty and a provocation to the male students, Crum Brown chose to award the Hope Scholarship to men whose names appeared lower on the list.

This had important consequences. It made national headlines in The Times and drew attention to the difficulties being encountered by a small group of women studying medicine at Edinburgh University.

"[Miss Pechey] has done her sex a service, not only by vindicating their intellectual ability in an open competition with men, but still more by the temper and courtesy with which she meets her disappointment" [11]

Research

Crum Brown's pioneering work concerned the development of a system of representing chemical compounds in diagrammatic form. In 1864 he began to draw pictures of molecules, in which he enclosed the symbols for atoms in circles, and used dashed lines to connect the atomic symbols together in a way that satisfied each atom's valence. The results of his influential work were published in 1864[6][12] and reprinted in 1865.[13]

Although Crum Brown apparently never contemplated the practice of medicine, his training as a medical student gave him an interest in physiology and pharmacology which led him to collaborate during 1867–8 with T. R. Fraser, a distinguished medical graduate a few years younger than himself, in a pioneering investigation of fundamental importance on the connection between chemical constitution and physiological action. Their method "consists in performing upon a substance a chemical operation which shall introduce a known change into its constitution, and then examining and comparing the physiological action of the substance before and after the change." The change considered was the addition of ethyl iodide to various alkaloids and comparison of the iodides (and the corresponding sulfates) thus obtained with the hydrochlorides of the original alkaloids. Striking regularities were observed, amongst others "that when a nitrile [tertiary] base possesses a strychnialike action, the salts of the corresponding ammonium [quaternary] bases have an action identical with curare [poison]."[6]

He discovered the carbon double bond of ethylene, which was to have important implications for the modern plastics industry. He also made significant contributions to pharmacology, and worked with physiology, phonetics, mathematics and crystallography.[6]

In 1912, he introduced the name of kerogen to cover the insoluble organic matter in oil shale.[14]

Personal life

Although physically not very robust, Crum Brown spent much of his holiday time in tramping in the highlands and on the continent, and was rarely ill. He married early in his professorial life, to Jane Bailie Porter (d.1910), the sister of (1) William Archer Porter, a lawyer and educationist who served as the Principal of Government Arts College, Kumbakonam and tutor and secretary to the Maharaja of Mysore, (2) James Porter (Master of Peterhouse, Cambridge) and (3) Margaret Archer Porter, who married Peter Tait (physicist). He remained intellectually active until his death in Edinburgh in 1922.[6]

Death

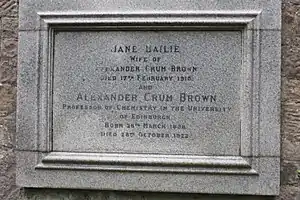

Crum died 28 October 1922 and is buried on the obscured southern terrace of Dean Cemetery.

Artistic Recognition

His sketch portrait of 1884, by William Brassey Hole, is held by the Scottish National Portrait Gallery.[15]

Other Recognition

In 2015 the City of Edinburgh Council agreed a request by the University of Edinburgh to name a street within the King's Buildings complex after Crum Brown.

References

- Edinburgh and Leith Post Office directory 1838-9

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Scotland's People http://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/welcome.aspx Baptism 6 May 1838 BROWN ALEXANDER CRUM JOHN BROWN/MARGARET FISHER CRUM FR4534 (FR4534) M EDINBURGH EDINBURGH CITY CITY/MIDLOTHIAN 685/01 0610 0266

- "Archived item". Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- Crum Brown, Alexander (1 January 1861). "On the theory of Chemical Combination". hdl:1842/2436. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Edgar F. Smith; W. R. Dunstan; B. A. Keen; Frank Wigglesworth Clarke (1923). "Obituary notices: Charles Baskerville, 1870–1922; Alexander Crum Brown, 1838–1922; Charles Mann Luxmoore, 1857–1922; Edward Williams Morley, 1838–1923; William Thomson, 1851–1923". J. Chem. Soc., Trans. 123: 3421–3441. doi:10.1039/CT9232303421.

- "Chairs and Professors of Universities in the United Kingdom". Who's Who Year-book for 1905. 1908. p. 132.

- In Memories and Adventures, Doyle writes 'There was kindly Crum Brown, the chemist, who sheltered himself carefully before exploding some mixture, which usually failed to ignite, so that the loud "Boom!" uttered by the class was the only resulting sound. Brown would emerge from his retreat with a "Really, gentlemen!" of remonstrance, and go on without allusion to the abortive experiment. .'

- "Recent History | School of Chemistry". www.chem.ed.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- "List of the Ordinary Fellows of the Society". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 26 (1): xi–xiii. 1870. doi:10.1017/S008045680002648X.

- Roberts, Shirley (1993). Sophia Jex-Blake: A woman pioneer. Routledge. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-415-75606-8.

- A. Crum Brown (1864) "On the Theory of Isomeric Compounds," Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 23 : 707–719.

- A. Crum Brown (1865). "On the Theory of Isomeric Compounds". J. Chem. Soc. 18: 230–245. doi:10.1039/JS8651800230.

- Teh Fu Yen; Chilingar, George V. (1976). Oil Shale. Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-444-41408-3. Retrieved 31 May 2009.

- Hole, William Brassey. "Professor Alexander Crum Brown, 1838 - 1922. Professor of Chemistry and Chemical Pharmacy at Edinburgh University". National Galleries Scotland. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: J.W. (possibly J. Walker) (1923). "Obituary notices". J. Chem. Soc., Trans. 123: 3421–3441. doi:10.1039/CT9232303421.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: J.W. (possibly J. Walker) (1923). "Obituary notices". J. Chem. Soc., Trans. 123: 3421–3441. doi:10.1039/CT9232303421.

Further reading

- Testimonials in favour of Alexander Crum Brown (Muir and Paterson, Edinburgh,1869).

- Brown, A.C., Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 23,707–720 (1864).

- Brown, A.C., Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 24, 331–9 (1867).

- Brown, A.C., Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 17, 181–5 (1891).

- Brown, A.C. and Walker, J., Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 36,211–224 (1892); Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 37, 361–379 (1895).

- Brown, A.C. and Gibson, J., Chemical Society Transactions, 61, 367–9 (1892).

- Horn, D.B., A Short History of the University of Edinburgh (University Press, Edinburgh, 1967), p. 194.

- National Library of Scotland MS 2636, f. 182.

- Rorie, D., University of Edinburgh Journal, 6,8–15 (1933–34).

- Flett, J.S., University of Edinburgh Journal, 15,160–182 (1949–1951 ).

- Bell, F.G., University of Edinburgh Journal, 20,215–230 (1961–1962).

- Edinburgh University Library MS Gen. 47D.

- Kendall, J., Journal of Chemical Education, 4,565–9 (1927).

- Report of the Royal Commissioners on the Universities of Scotland, vol. II (Evidence-Part I) (H.M.S.O., Edinburgh, 1878), pp. 184–5.

- Quasi Cursores (Constable, Edinburgh, 1884), pp. 229–232.

- Kendall, J., Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society, 1,537–549 (1932–35):

- Edinburgh University Library MS Gen. 178/3,4.

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Alexander Crum Brown |

External links

- Biography of Crum Brown, School of Chemistry, University of Edinburgh

- Web pages on Crum Brown at University of Edinburgh