Alaíde Foppa

Alaíde Foppa (1914 – c. 1980?) was a poet, writer, feminist, art critic, teacher and translator. Born in Barcelona, Spain she held Guatemalan citizenship and lived in exile in Mexico. She worked as a professor in both Guatemala and Mexico. Much of her poetry was published in Mexico and she co-founded one of the first feminist publications, Fem, in the country. After her husband's death, she made a trip to Guatemala to see her mother and renew her passport. She was detained and disappeared in Guatemala City on 19 December 1980, presumed to be murdered. Some sources note the date of her disappearance as 9 December 1980.[1]

Alaíde Foppa | |

|---|---|

| Born | María Alaíde Foppa Falla 3 December 1914 |

| Died | Disappeared, presumed dead 19 December 1980 (age 66) |

| Nationality | Guatemalan |

| Other names | de Solórzano |

| Occupation | Educator, poet |

| Years active | 1940-1980 |

Biography

María Alaíde Foppa Falla was born 3 December 1914 in Barcelona, Spain to Tito Livio Foppa and Julia Falla. Her mother was a pianist[2] of Guatemalan descent and her father was an Argentine-[3] Italian[4] diplomat. She grew up traveling, living in Belgium, France and Italy.[5] She was educated in Italy, studying the history of art and literature. She spoke fluent Italian and worked for several years as a translator.[6]

In the 1940s, Foppa attained Guatemalan citizenship,[7] and married a Guatemalan leftist, Alfonso Solórzano.[8] A member of the FDN, he was an "intellectual communist",[9] who managed the Guatemala Institute of Social Security.[10] Solórzano eventually also served as a cabinet adviser to Guatemalan president Jacobo Árbenz[11] With Solórzano, she had four children, born in Mexico: Mario, Juan Pablo, Silvia[8] and Laura.[5] Foppa's oldest son Julio was the child of Juan José Arévalo, Árbenz's predecessor as president of Guatemala.

Foppa served on the faculty of the humanities department at the Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala (University of San Carlos of Guatemala) and was a founder of the Italian Institute of Culture in the Central American country. She and her husband were forced to flee the country in 1954 when the presidency of Jacobo Árbenz[7] was overthrown by a CIA-backed military coup.

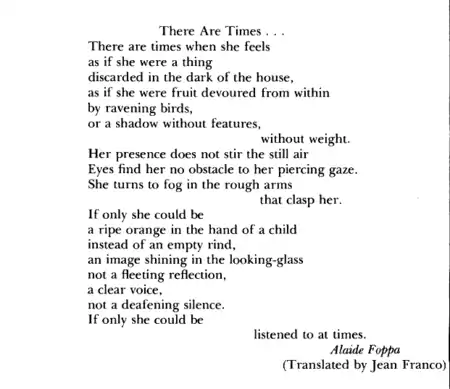

Foppa lived in exile in Mexico, working as a professor at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM),[3] where she taught Italian at the School of Philosophy and Letters and offered the first-ever course at a Latin American university on the sociology of women.[12] She lectured at other institutions, published columns and served as an art critic in local newspapers,[6] and she wrote much of her poetry in Mexico City.[3] It is believed that other than a volume called Poesías printed in Madrid and La Sin Ventura published in Guatemala, all her other poetic works were published in Mexico, though she wrote and edited some of them at her family's farm in the Sacatepéquez Department, while visiting her mother.[2]

In 1972, she created the radio program "Foro de la Mujer" (Women's Forum) which was broadcast on Radio Universidad, to discuss inequalities within Mexican society, violence and how violence should be treated as a public rather than a private concern, and to explore women's lives. In 1975, she co-founded with Margarita García Flores the publication Fem, a magazine for scholarly analysis of issues from a feminist perspective.[14] Foppa financed the publication from her own funds.[6] Important Mexican journalists and intellectuals aided in the co-founding of the magazine.[15] Many prominent Latin Americans in the early 1980s did not identify with "Feminism" but rather with "Humanism", as in the case of Griselda Alvarez when asked by Fem.[15]

Foppa was also a regular participant in events with Amnesty International and the International Association of Women Against Repression (AIMUR).[6] With others of the Guatemalan intellectual community, Foppa denounced the government for human rights violations and her name began appearing on published lists of "subversives".[11]

Disappearance

When her husband Solórzano was struck and killed by a car, Foppa went to Guatemala,[8] ostensibly to visit her mother[5] and renew her passport,[2] but it was believed she had decided to work for the guerrillas. By one account, she had engaged in a guerrilla courier mission to Guatemala City, where she was promptly captured by government security forces.[16] Both of her sons Mario and Juan Pablo, though born in Mexico, had returned to fight with the guerrilla forces in Guatemala and were killed. Her daughter, Silvia, who also supported the rebels, had been in hiding in Cuba for a while[8] and at the time of Foppa's disappearance was back in Guatemala.[5]

Foppa's daughter Laura was a dancer and was performing in a production at the Covarrubias Theatre that was to open on 21 December 1980. When she called to verify that her mother would be returning for the performance, she learned from her grandmother of her mother's disappearance with the chauffeur, Leocadio Axtún Chiroy. Oldest son, Julio Solórzano Foppa, got a phone call from Laura who imparted the news to him and oldest daughter, Silvia learned of her mother's disappearance on the radio in a guerrilla camp in the mountains of El Quiché.[5]

Foppa had apparently gone to buy flowers and pick up her passport[5] in Guatemala City on 19 December 1980.[3] She was accompanied by her mother's driver, Leocadio Axtún, who had taken her to the Plaza El Amate, where they were intercepted, and never heard from again.[5] Rumors were that she was tortured by a death squad of a high-ranking minister and killed the same day she was captured.[11] Initially the newspapers carried a report that she had been abducted by members of the G-2 intelligence unit, beaten, and forced into a car, which sped away, but fearful of retaliation witnesses would not come forward.[17]

When news of the disappearance reached friends and family, they mobilized. Daughter Laura, who had won a grant to study dance in New York, used the trip to visit both the United Nations and the office of human rights of the Organization of American States. Julio, flew to Paris and with the help of friends secured an audience with the Legislative Assembly in an attempt to put international pressure on the Guatemalan government.[5] Friends wrote letters and formed committees to demand action from the Guatemalan authorities.[12][18]

Julio returned to Mexico and met with Jorge Castañeda y Álvarez de la Rosa, Mexican Secretary of Foreign Affairs. Mexican president Jose Lopez Portillo authorized a commission of legal scholars, journalists and Foppa's children to go to investigate the disappearance; however, right before the group was to leave, a veiled threat was received telling them they were welcome to come but that "international communism, in its efforts to make the Guatemalan government look bad, may cause harm… to come to them." The group decided the risk was too great, since Foppa was probably not still alive.[11]

On 2 December 1999, Foppa's children requested that the Audiencia Nacional de España open an inquiry. Though a case was opened, Guatemalan authorities did not respond.[19] In 2005, an explosion at an obscure police station on the outskirts of Guatemala City revealed an archive of records going back to the creation in 1880 of the National Police. Forensic teams began examining the documents in the Guatemala National Police Archives, and Julio Solórzano wanted to ensure that the documents remained accessible. He contacted Karen Engle at the University of Texas’ Rapoport Center for Human Rights and persuaded them to digitize the records. He is hopeful that within the archive is information on his mother's case.[11]

In 2010, Foppa's family, Grupo de Apoyo Mutuo (GAM) (Mutual Support Group) and the Centro de Reportes Informativos sobre Guatemala (CERIGUA) (Center of Informative Reports on Guatemala) and other organizations demanded that an inquiry into Foppa's disappearance be launched by Guatemalan authorities.[19][20] In 2012, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) filed a complaint against Guatemala's inaction on the case.[21] In 2014, Foppa's daughter Silvia concurred that there was no resolution from any of the court actions—in Spain, before the Guatemalan Supreme Court, or from the IACHR case. The whereabouts of Foppa and what happened to her is still unanswered. In 2014, a documentary by Maricarmen de Lara entitled “¡Alaíde Foppa, la sin ventura!” (Alaide Foppa, without luck) was released.[22]

Selected works

- Poesías (Madrid) (1945)

- La Sin Ventura (Guatemala) (1955)

- Los dedos de mi mano (Mexico) (1958)

- Aunque es de noche (Mexico) (1962)

- Guirnalda de primavera (Mexico) (1965)

- Elogio de mi cuerpo (Mexico) (1970)

- Las palabras y el tiempo (Mexico) (1979)

See also

References

- Foppa, A., & Franco, J. (1981). [Alaide Foppa de Solórzano]. Signs, 7(1), 4-4. JSTOR 3173501

- "Cien años de Alaíde Foppa" (in Spanish). Guatemala City, Guatemala: El Periódico. 3 December 2014. Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- Agosín 1994, p. 168.

- Foppa 2000, p. 1.

- Vargas, Vania (30 November 2014). "Alaíde Foppa: El corazón tiene el tamaño de un puño cerrado" (in Spanish). Guatemala City, Guatemala: El Periódico. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- Zamora Márquez, Anaiz (5 December 2014). "Abiertos tres juicios por desaparición de feminista Alaíde Foppa" (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: Cimac Noticias. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- "¿Quién fue Alaíde Foppa?" (in Spanish). Cable News Network en Español. 4 December 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- Poniatowska, Elena (21 October 2012). "Alaíde Foppa: 31 años después". La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- Brecher 1978, p. 102.

- Schlesinger, Kinzer & Coatsworth 2005, p. 137.

- Elbein, Saul (30 March 2012). "The Long Road Home". The Texas Observer. Austin, Texas. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- "Missing Person". The New York Review of Books. New York: The New York Review of Books. 17 December 1981. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- Hernandez, Jennifer Browdy de (2003). Women Writing Resistance: Essays on Latin America and the Caribbean. South End Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-89608-708-8.

- Parra Toledo, Alejandra (3 October 2005). "Fem publicación feminista pionera en América Latina se convierte en revista virtual". La Jornada (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- Mariscal, Sonia. (2014). “I am not a feminist!!!” Feminism and its Natural Allies, Mexican Feminism in the 70s/80s. Thinking Gender 2014. UCLA: UCLA Center for the Study of Women. Retrieved from: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/7c7114jz

- Guillermoprieto, Alma (2002). Looking for history : dispatches from Latin America. New York: Vintage Books. p. 83. ISBN 030742667X. OCLC 712672478.

- "City of the Disappeared – three decades of searching for Guatemala's missing". Amnesty International. Amnesty International. 19 November 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- "1980: Alaíde Foppa de Solorzano". PEN International. London: PEN International. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- "CERIGUA demands inquiry into journalist's disappearance". IFEX network. Toronto, Canada: International Free Expression Network. 23 November 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- Dore, A., Asher, A., Bernikow, L., Chevigny, B., & Christ, R. et al. (1981). Missing Person. The New York Times Review of Books, 28(20). Retrieved September 29, 2017, from http://www.nybooks.com/articles/1981/12/17/missing-person/

- "CIDH conoce denuncia por desaparición forzada de Alaíde Foppa en 1980" (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: Sin Embargo. 27 June 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- López García, Guadalupe (22 December 2014). "Hija de Alaíde Foppa trae a México reclamo de justicia" (in Spanish). Queretaro, Mexico: Diario Rotativo. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

Bibliography

- Agosín, Marjorie (1994). These are Not Sweet Girls: Latin American Women Poets. White Pine Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-1-877727-38-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brecher, Michael (1978). Studies in Crisis Behavior. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-3536-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Foppa, Alaíde (2000). Antología poética. Librerias Artemis Edinter. ISBN 978-84-89766-72-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schlesinger, Stephen; Kinzer, Stephen; Coatsworth, John H. (2005). Bitter Fruit: The Story of the American Coup in Guatemala, Revised and Expanded (Series on Latin American Studies). Aware Journalism. ISBN 978-0-674-01930-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)