Airport malaria

Airport malaria, sometimes known as baggage,[1] luggage[2] or suitcase malaria,[3] occurs when a malaria infected female Anopheles mosquito travels by aircraft from a country where malaria is common, arrives in a country where malaria is usually not found, and bites a person at or around the vicinity of the airport, or if the climate is suitable, travels in luggage and bites a person further away.[4][5] The infected person usually presents with a fever in the absence of a recent travel history. There is often no suspicion of malaria, resulting in a delay in diagnosis and often death. Other causes of imported malaria need to be excluded first.[6]

| Airport malaria | |

|---|---|

| Other names |

|

| |

| Anopheles gambiae mosquito | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Unexplained fever associated with

|

| Causes |

|

| Diagnostic method |

|

| Prevention | |

| Prognosis | Potentially fatal |

| Frequency | Uncommon |

Most mosquitoes on aircraft do not carry malaria and the few that do are relatively inefficient invaders. The climate of the host country also offers natural protection. The detection and treatment is the same as of malaria in general. Prevention involves control of mosquitoes at and around airports in the countries of departure and on the aircraft.[7]

Studies of airport malaria have been largely observations of individual scenarios, all unique in timing, place of infection and problems, in addition to possibilities of error.[8]

Background

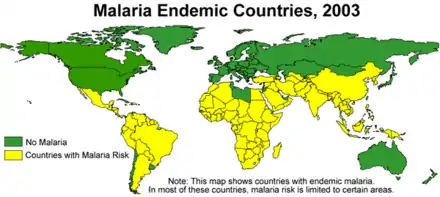

Human malaria is native to 97 countries and is the world's most prevalent vector-borne disease with 212 million new cases in 2015.[1] Any occurrences outside endemic countries are largely imported cases or less commonly malaria with no recent travel history.[1]

Airport malaria is defined as malaria acquired at or near an airport through the bite of an infected tropical Anopheles mosquito by a person who has no history of being exposed to the mosquitoes in their natural habitat.[9] Malaria transmission in-flight or on a stop-over is not considered airport malaria.[7]

Causes

Although most imported malaria is due to travel by infected humans,[10] airport malaria is specifically caused by the transmission of malaria parasites to a human through the bite of a malaria infected mosquito that has travelled by aircraft on an international flight from a country where malaria is usually found to a country where malaria is usually not found. It occurs at or around the vicinity of the airport.[9] Very few mosquitoes however enter aircraft and of those that do, less than 5% are likely to carry malaria.[10] Of the four different species of the protozoan parasite Plasmodium; Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium malariae, Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium ovale,[11][12] airport malaria is most commonly the falciparum and less commonly the vivax type.[7] These can only be transmitted by female Anopheles mosquitoes, which bite mainly between dusk and dawn.[11][12]

Five infection pathways have been described: inside the aircraft, inside the airport, around the airport, far from the airport and from luggage.[8]

Expansion of mosquito habitats

Deforestation, and projects involving housing, agriculture and water can incidentally expand mosquito habitats.[13] Economic necessity, disasters and conflicts, are known to affect the migration of people, which can also contribute to the movement of mosquitoes and hence risk of malaria. Failure to take this into account has previously resulted in failed attempts to control malaria.[9]

Air traffic and global warming

With an increase in air traffic volume, higher climate temperatures and humidity, the summers of temperate climates are potentially favourable for mosquitoes. Should temperatures rise in Europe and the United States as a result of global climate change, conditions may become more ideal for mosquito survival, potentially leading to a rise in isolated outbreaks of airport and imported malaria. Uninfected mosquitoes that arrive by flight may also live for long in enough as to feed on an infected person, which could also result in the transmission of malaria in non-endemic countries.[9][14][15]

Airports, air routes and aircraft

Airports

The highest risk of airport malaria in Europe is from western and central Africa. A number of species have been found in these Western European airports, particularly Anopheles gambiae which breeds in Africa's rainy season during summer, when conditions in Europe are more favourable for its survival.[2]

When the cabin and cargo hold doors are opened, ground personnel working on airstrips are at risk. Also, those who manipulate and open containers in warehouses, stores or the post office are exposed to bites of the mosquitoes which have travelled in containers.[7]

Air routes

The increase in air routes from Africa potentially increase the risk of introducing airport malaria.[17]

Aircraft

Mosquitoes have been found to be attracted to the illuminated cabins rather than to the baggage compartments.[18]

Diagnosis

Mild cases may be missed.[8] Due to the absence of a travel history in a person with fever, malaria is not usually expected, resulting in delays in diagnosis. Before the diagnosis of airport malaria can be made, other methods of transmission need to be excluded including blood transfusion, shared needles, prior exposure in endemic regions, and transmission by local mosquitoes.[6] History taking requires information on where the person lives and works, in addition to the distance from the airport.[1]

Epidemiology

Airport malaria is rare[17] with most cases being reported sporadically[5] and in the summer.[7] It is not as well recognised as malaria in a person with a travel history to a place with endemic malaria.[6]

Europe

Between 1969 and 1999, Europe saw up to 89 people diagnosed with airport malaria. The frequent flights from Sub-saharan Africa resulted in Belgium, France and the Netherlands being at highest risk.[5][18]

In the UK, at least 14 people with airport malaria were reported between 1969 and 1999.[19] In 1983, 12 out of 67 aircraft flying from tropical countries to Gatwick Airport, London, contained mosquitoes. In the same year, falciparum malaria was reported in two people living 10 km (6.2 mi) and 15 km (9.3 mi) from Gatwick Airport.[18] It was deduced that an infected mosquito accompanied aircrew to a pub near Gatwick and infected its landlord.[20] It was also construed that the same stowaway mosquito also transmitted malaria to a woman who rode through the same village on her motor scooter.[8][21][22] High minimum temperatures and humidity were thought to have allowed the infected anopheline mosquitoes to enter the country via aircraft and facilitate their survival.[9][23] Reports of transmission taking place on the aircraft occurred in the UK in 1984 and 1990, the only such reports on aircraft, leading to infection on aircraft being described as a "British speciality".[8] In 2002, one report came from the vicinity of Heathrow airport.[19]

In France, most flights at risk arrive at Charles de Gaulle Airport, Paris, and to a much lesser extent at Marseille, Nice, Lyon, Bordeaux and Toulouse.[7] In 1994, airport malaria was identified in and around Charles de Gaulle Airport in six people, of which four were airport workers, and the others lived 7.5 km (4.7 mi) away in Villeparisis. It was thought that the mosquitoes traveled in the cars of airport workers who lived next door to the two people.[9] All were caused by P. falciparum.[7]

In 1989, two cases of falciparum malaria were identified in Italy in two people who lived in Geneva.[9] Distance from the nearest airport ruled out airport malaria in one woman who developed malaria in Italy. A local mosquito (Anopheles labranchiae) had bitten a girl with malaria from India and passed it on. This species was a common malaria vector in Italy until the country was declared malaria free in 1970.[9] Five cases of airport malaria were reported in Geneva in the hot summer of 1989.[9]

In Spain, 1964 marked the elimination of malaria following sanitary and socioeconomic developments. However, over the following 50 years, more than 10 000 cases of malaria were reported, of which 0.8% had no history of recent travel. Airport malaria was reported in two people. In 1984, a 76-year-old woman died from P. falciparum after visiting relatives less than 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) from Madrid airport. Suspected to have pneumonia, the diagnosis was not initially clear. In 2001, a second woman was diagnosed, treated and recovered.[1]

Other countries

In the United States, between 1957 and 2003, there were 156 people reported with malaria who had no history of travel or other risk factors. Some were likely to be caused by airport malaria.[13] A small number of airport malaria reports have come from Florida.[24]

Airport malaria was first reported in Australia in 1996.[25][26]

Prevention

The WHO International Health Regulations give guidance on prevention of airport malaria. Mosquito control programmes also recommend procedures for aircraft coming from endemic areas and for the receiving airports, including the surrounding 400 metres (1,300 ft) of area.[1]

Routine aircraft disinsection of aircraft has been shown to reduce mosquitoes on aircraft.[17] Insecticide can also be sprayed on the ground. However, these procedures are not totally efficient and they vary from country to country.[5]

Most mosquitos on aircraft do not carry malaria. The few that do are relatively inefficient invaders. In addition, further natural protection is offered by constraints of the hosting country's climate.[5]

A list of airports at risk has been proposed.[7] International sanitary regulations require the area of airports and the perimeter of 400 m (1,300 ft) around the airport to be made free of Aedes aegypti and Anopheles mosquitos. However, the application of disinsection varies from country to country.[7]

Outlook

Airport malaria is not considered a serious public health problem but has a high fatality rate and poses a local threat. The prognosis is poor with fatality rates ranging from 16.9% to 26% with almost all the reports being of the falciparum type.[8]

History

There were reports from as early as 1925 that diseases including cholera, plague, smallpox, typhus, yellow fever and malaria could make their way across countries within short periods of time on aircraft.[27] Based on the International Sanitary Convention for Aerial Navigation (1933) (Hague), which came into force in 1935 to protect communities against diseases liable to be imported by aircraft,[28] air-traffic health control administrations, dealt with by the Office International d'Hygiène Publique, Paris, were able to impose maximally excepted measures for this purpose, but left their actual application to each country concerned. Information regarding disease surveillance was supplied by "The Health Organization of the League of Nations" and updates were published and circulated regularly. Individual governments drew up their own regulations accordingly. To prevent the introduction of infectious diseases from abroad into the United Kingdom, the Public Health (Aircraft) Regulations 1938 was issued by the Ministry of Health. Its actions included the "disinsection of aircraft in the tropics and subtropics to prevent yellow fever and malaria-infected mosquitoes from being introduced into the country".[27]

In 1928, the first report of insects on aircraft came from the quarantine inspector of the dirigible Graf Zeppelin on its arrival in the United States.[18] Airport malaria was later first documented in 1969.[7] Until 1970, malaria was endemic in Europe.[29]

Research directions

Epidemiological and entomological surveillance and research on the interconnection between malaria transmission and population movement requires attention, as to is improvement in living facilities to prevent forced movement of people, awareness of the connection between mosquitoes and malaria, in addition to adequate healthcare and the control of urbanization.[1][9]

Airport malaria poses a potential risk to the local spread of malaria. The UK is home to five species of anopheline mosquitoes, of which only Anopheles atroparvus breeds close enough in proximity to humans and in enough numbers to act as an efficient vector for malaria.[24] A serious public health problem would arise if the introduction of infected mosquitoes led to the transmission of malaria by local mosquitoes, particularly if transmission were revived in an area where the disease had previously been endemic and then eradicated.[18]

References

- Velasco E, Gomez-Barroso D, Varela C, Diaz O, Cano R (June 2017). "Non-imported malaria in non-endemic countries: a review of cases in Spain". Malaria Journal. 16 (1): 260. doi:10.1186/s12936-017-1915-8. PMC 5492460. PMID 28662650.

- Sabatinelli G (2002). "6. Determinants of Malaria in WHO European Region". In Casman EA, Dowlatabadi H (eds.). The Contextual Determinants of Malaria. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-891853-19-7.

- "Multiple reports of locally-acquired malaria infections in the EU" (PDF). European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Stockholm. 20 September 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- "NaTHNaC - Malaria". Travel Health Pro. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- Lambrechts L, Cohuet A, Robert V (2011). Simberloff D, Rejmanek M (eds.). Encyclopedia of Biological Invasions. University of California Press. p. 445. ISBN 9780520264212.

- Isaäcson M (1989). "Airport malaria: a review" (PDF). Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 67 (6): 737–43. PMC 2491318. PMID 2699278.

- Guillet P, Germain MC, Giacomini T, Chandre F, Akogbeto M, Faye O, Kone A, Manga L, Mouchet J (1998). "Origin and prevention of airport malaria in France". Tropical Medicine & International Health. 3 (9): 700–705. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00296.x. ISSN 1365-3156. PMID 9754664.

- Sylvie, Manguin; Pierre, Carnevale; Jean, Mouchet (2008). "Airport malaria". Biodiversity of Malaria in the world. John Libbey Eurotext. pp. 334–336. ISBN 9782742006168.

- Martens P, Hall L (2000). "Malaria on the move: human population movement and malaria transmission". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 6 (2): 103–9. doi:10.3201/eid0602.000202. PMC 2640853. PMID 10756143.

- Mier-y-Teran-Romero, Luis; Tatem, Andrew J.; Johansson, Michael A. (3 July 2017). "Mosquitoes on a plane: Disinsection will not stop the spread of vector-borne pathogens, a simulation study". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 11 (7): e0005683. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005683. ISSN 1935-2727. PMC 5510898. PMID 28672006.

- "International travel and health; Malaria". WHO. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- "Do all mosquitoes transmit malaria?". WHO. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- Hartjes, Laurie B. (June 2011). "Preventing and Detecting Malaria Infections". The Nurse Practitioner. 36 (6): 45–53. doi:10.1097/01.NPR.0000397912.05693.20. ISSN 0361-1817. PMC 3150182. PMID 21572299.

- "Airport Malaria: Cause For Concern In U.S." ScienceDaily. 12 November 2008. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- Osterholm, Michael T.; Olshaker, Mark (2017). Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0316343695.

- "OpenFlights: Airport and airline data". openflights.org. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Tatem, Andrew J; Rogers, David J; Hay, Simon I (14 July 2006). "Estimating the malaria risk of African mosquito movement by air travel". Malaria Journal. 5: 57. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-5-57. ISSN 1475-2875. PMC 1557515. PMID 16842613.

- Gratz, N. G.; Steffen, R.; Cocksedge, W. (2000). "Why aircraft disinsection?". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 78 (8): 995–1004. ISSN 0042-9686. PMC 2560818. PMID 10994283.

- Berger, Stephen (2018). Malaria: Global Status. GIDEON Informatics Inc. pp. 505–507. ISBN 9781498820370.

- Lashley, Felissa R.; Durham, Jerry D. (2007). Emerging Infectious Diseases: Trends and Issues, Second Edition. Springer Publishing Company. ISBN 9780826102508.

- Uhlig, Robert (28 August 2002). "Man contracts malaria in Britain". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- Whitfield, D; Curtis, C F; White, G B; Targett, G A; Warhurst, D C; Bradley, D J (8 December 1984). "Two cases of falciparum malaria acquired in Britain". British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.). 289 (6458): 1607–1609. doi:10.1136/bmj.289.6458.1607. ISSN 0267-0623. PMC 1443914. PMID 6439340.

- "Malaria – Amazonia Foundation". www.amazoniafoundation.org. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- Welsby, P. D.; Chin, T. (1 November 2004). "Malaria in the UK: past, present, and future". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 80 (949): 663–666. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2004.021857. ISSN 0032-5473. PMC 1743127. PMID 15537852.

- Whelan, Peter; Nguyen, Huy; Hajkowicz, Krispin; Davis, Josh; Smith, David; Pyke, Alyssa; Krause, Vicki; Markey, Peter (27 September 2012). "Evidence in Australia for a Case of Airport Dengue". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 6 (9): e1619. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001619. ISSN 1935-2727. PMC 3459876. PMID 23029566.

- Jenkin, G. A.; Ritchie, S. A.; Hanna, J. N.; Brown, G. V. (1997-03-17). "Airport malaria in Cairns". The Medical Journal of Australia. 166 (6): 307–308. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb122319.x. ISSN 0025-729X. PMID 9087188.

- Whittingham, H. E. (March 1939). "Preventive Medicine in Relation to Aviation". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 32 (5): 455–472. doi:10.1177/003591573903200533. ISSN 0035-9157. PMC 1997529. PMID 19991846.

- "The Postal History of ICAO". www.icao.int. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- "New map shows the presence of Anopheles maculipennis s.l. mosquitoes in Europe". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 12 September 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

| Classification |

|---|