African historiography

African historiography is a branch of historiography concerning the African continent, its peoples, nations and variety of written and non-written histories. It has differentiated itself from other continental areas of historiography due to its multidisciplinary nature, as Africa’s unique and varied methods of recording history have resulted in a lack of an established set of historical works documenting events before European colonialism. As such, African historiography has lent itself to contemporary methods of historiographical study and the incorporation of anthropological and sociological analysis.

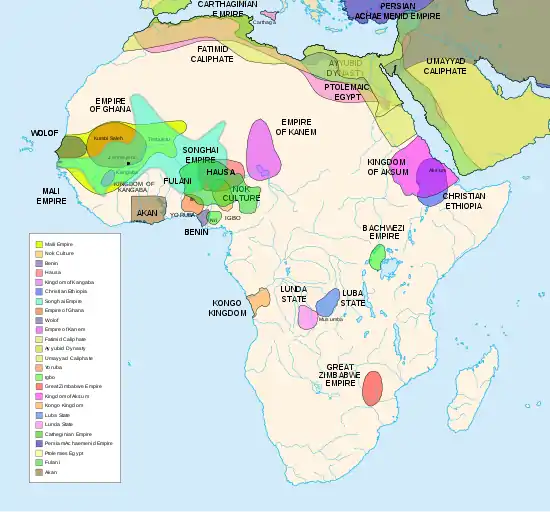

The chronology of African recorded history encompasses many movements of art, African nations and dialects, and its history has permeated through many mediums. History concerning the much of the pre-colonialist African continent is depicted through art or passed down through word of mouth. As European colonization emerged, the cultural identity and socio-political structure of the continent drastically shifted, and the written documentation of Africa and its people was dominated by European academia, which was later acknowledged and criticized in post-colonialist movements of the 20th century.

Antiquity

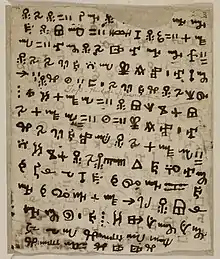

Africa, due to both its expanse, varied and often harsh terrain, and variety of cultural groups lacked the capability to collectivize to the extent of Eastern Europe, Asia Minor or the Middle East. As a result, much of the African continent did not reach the technological advancement of the northernmost kingdoms and nations of Africa.[1] Much of the depiction of Africa preceding written history is through archaeology and antiquities. Excluding Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs and the Ge’ez script, a large part of the African continent would not have a means of writing or recording history until the common era. This presents a challenge for historians in deciphering the history of the continent with certain people and nations yet to begin recording history.

Early Written History

Many African writing systems have been developed in ancient and recent history, and the continent holds a large quantity of varied orthographies. One of the most notable ancient languages were the Egyptian Hieroglyphs, which were often found carved into walls, as decoration on objects of religious significance and written on wood and papyrus.[2] Hieroglyphs, like many other ancient African dialects, underwent a considerable period of time where there was no verifiable translation. The Rosetta Stone, discovered in 1799, would allow historians to effectively decipher Hieroglyphs and access a new field of Ancient Egyptian history.[3] This field would be undertaken predominantly by European historians.

Colonial historiography

Colonial History arrived with the discovery and colonization of Africa and involved the study of Africa and its history by European academics and historians.[4] Due to the relative establishment of European academia compared to Africa during the period, as well as the domination of European powers across the continent, African History was written from an entirely European perspective under the pretense of Western Superiority.[5] This predilection stemmed from the technological superiority of European nations and the decentralization of the African continent with no nation being a clear power in the region, as well as a perception of Africans as racially inferior.[6] Another factor was the lack of an established body of collective African history created in the continent, there being instead a multitude of different dialects, cultural groups and fluctuating nations as well as a diverse set of mediums that document history other than written word. This led to a perception by Europeans that Africa and its people had no recorded history and had little desire to create it.[7]

The historical works of the time were predominantly written by scholars of the various European powers and were confined to individual nations, leading to disparities in style, quality, language and content between the many African nations.[4] These works mostly concerned the activities of the European powers and centered on events concerning economic and military endeavors of the powers in the region.[5] Examples of British works were Lilian Knowles' The Economic Development of the British Overseas Empire and Allan McPhees The Economic Revolution in British West Africa, which discuss the economic achievements of the British empire and the state of affairs in African nations controlled by Britain.[5]

Institutions

African historiography became organized at the academic level in the mid-20th century.[8] The School of Oriental Studies opened at the University of London in 1916. It became the School of Oriental and African Studies in 1938 and has always been at the center of scholarship on Africa. In the U.S. Northwestern University launched its Program of African Studies in 1948. The first scholarly journals were founded: Transactions of the Gold Coast & Togoland Historical Society (1952); Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria (1956); The Journal of African History (1960); Cahiers d’études africaines (1960); and African Historical Studies (1968). Specialists grouped together in the African Studies Association of the US (1957)' the African Studies Association of the UK (1963); the Canadian Association of African Studies/Association Canadienne des Etudes Africaines (1970).

North Africa

European imperialism impacted escalated in North Africa after 1800. This included the British seizure of control of Egypt (1882). France operated a large expansionist program in Egypt (1798), Algeria (1830); Tunisia (1881); and East Morocco (1912); as well as building and operating the Suez Canal (1854+). Spain fought the Moroccan War (1859/60), and sent settlers to Northern Morocco (1912). Italy focused on Libya (1911) and sent settlers to Algeria. Imperialism was reversed in dramatic fashion in the Algerian War (1954-1962), the Suez Crisis (1956) as well as the independence of Libya (1951), Morocco (1956) and Tunisia (1956).[9]

Modernization models 1945–1990

Modernization models were typical interpretive structures in African historiography from the end of World War II into the 1980s.[10] For example, Philip Curtin argued in 1981 that the main concerns of historians ought to be with:

- civilizations, institutions, structures: agrarian and metallurgical techniques, arts and crafts, trade networks, the conception and organization of power, religion and religious and philosophical thought, the problem of nations and pre-nations, techniques of modernization, and so on.[11]

Ethnohistory and anthropology

Anthropological work of Africa involves many fields of anthropology including cultural anthropology, social anthropology and linguistic anthropology in the pursuit of contextualizing and uncovering the human elements of history and is referred to as Ethnohistory. A methodology originally employed in the study of indigenous cultures, it has transitioned not only into the general field of anthropology but has been largely adopted by practitioners of history and the movement of social history.[1] From its focus on indigenous cultures and the analysis of the anthropological origins of a people rather than their political relations (which would be otherwise be dominated by their relevance to European nations), Ethnohistory approaches history from a point preceding European colonization, and allows for historians to study the implications of the Scramble for Africa with a greater understanding of the social stratification of African nations before and after colonialism. The depiction of these nations would go from being static to dynamic, documenting a progression from the time before and after the arrival of European nations, which is in part accomplished by a transition from the study of what has been done, to the means, methods and reasons of the actions undertaken.[12]

Post-colonialist historiography

Post-colonialist historiography studies the relationship between European colonialism and domination in Africa and the construction of African history and representation. It has roots in Orientalism, the construction of cultures from the Asian, Arabian and North African world in a patronizing manner stemming from a sense of Western superiority, first theorized by Edward Said.[13] A general perception of Western superiority throughout European academics and historians prominent during the height of colonialism led to the defining traits of colonial historical works, which post-colonialists have sought to analyse and criticize.

William Macmillan and the effect of colonialism

William Miller Macmillan is a historian and post-colonialist thinker. His historical work, Africa Emergent (1938), critiqued colonial rule and sought for the democratization of African nations in seeking African representation in governments. The work not only condemns colonial rule, but also considers the perspectives of and the effect of colonialism on the African people, a considerable difference from the works’ contemporaries.[14] He was a founder of the liberal school of South African historiography and as a forerunner of the radical school of historiography that emerged in the 1970s. He was also a critic of colonial rule and an early advocate of self-government for colonial territories in Africa and of what became known as development aid.

Edward Said and Orientalism

Said and his book Orientalism (1978) had a major impact on post-colonial studies. It introduced the theory of Orientalism and deconstructed the methods in which foreign cultures were distorted and patronized through western representation. One result was the sharp decline in use of modernization models based upon the European transition from traditionalism to modernity.[15]

Contemporary historiography

Acknowledgement and acceptance of African nations and peoples as individuals free of European domination has allowed African history to be approached from new perspectives and with new methods. Africa has lacked a defined means of communication or academic body due to its variety of cultures and communities, and the plurality and diversity of its many peoples means a historiographical approach that confines itself to the development and activity of a singular people or nation incapable of capturing the comprehensive history of African nations without a vast quantity of historical works.[12] This quantity and diversity of history that has yet to be documented is better suited to the contemporary historiographical movements that incorporate the social sciences: anthropology, sociology, geography and other fields that closer examine the human element of History rather than constrain it to political history.

See also

- The Cambridge History of Africa, a multivolume history published 1975-1986

- General History of Africa, a multivolume history edited by UNESCO an d published in 1980s

- East Africa

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- West Africa

References

- Axtell, James (1979). "Ethnohistory: An Historian's Viewpoint". Ethnohistory. 26 (1): 1–13. doi:10.2307/481465. ISSN 0014-1801. JSTOR 481465.

- Allen, James P. Middle Egyptian : an introduction to the language and culture of hieroglyphs. ISBN 9781107283930. OCLC 884615820.

- Powell, Barry B. (2009). Writing : theory and history of the technology of civilization. Chichester, U.K.: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781405162562. OCLC 269455610.

- Manning, Patrick (2013). "African and World Historiography". The Journal of African History. 54 (3): 319–330. doi:10.1017/S0021853713000753. ISSN 0021-8537. JSTOR 43305130.

- Roberts, A.D. (1978). "The Earlier Historiography of Colonial Africa". History in Africa. 5: 153–167. doi:10.2307/3171484. ISSN 0361-5413. JSTOR 3171484.

- Fanon, Frantz (December 2007). The wretched of the earth. Philcox, Richard; Sartre, Jean-Paul; Bhabha, Homi K. New York. ISBN 9780802198853. OCLC 1085905753.

- Cooper, Frederick (2000). "Africa's Pasts and Africa's Historians". Canadian Journal of African Studies. 34 (2): 298–336. doi:10.2307/486417. JSTOR 486417.

- Manning, 2013, p. 321.

- Manuel Borutta, and Sakis Gekas. "A colonial sea: The Mediterranean, 1798–1956." European Review of History 19.1 (2012): 1-13.

- Manning, "African and World Historiography". (2013)

- Curtin, "General Introduction," in Joseph Ki-Zerbo, ed. UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. I, Methodology and African Prehistory (1981) pp 22–23.

- Tignor, Robert L. (1966). "African History: The Contribution of the Social Sciences". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 4 (3): 349–357. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00013525. ISSN 0022-278X. JSTOR 159205.

- Said, Edward W. (1978). Orientalism (First ed.). New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0394428145. OCLC 4004102.

- Macmillan, William (1949). Africa emergent: a survey of social, political, and economic trends in British Africa. London, UK: Penguin Books.

- K. Humayun Ansari, "The Muslim world in British historical imaginations:‘re-thinking Orientalism’?." British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 38.01 (2011): 73-93 at 88–92. online.

Further reading

- Bates, Robert H., Vumbi Yoka Mudimbe, and Jean F. O'Barr, eds. Africa and the disciplines: The contributions of research in Africa to the social sciences and humanities (U of Chicago Press, 1993).

- Brown, Karen. "‘Trees, forests and communities’: some historiographical approaches to environmental history on Africa." Area 35.4 (2003): 343-356. online

- Clarence-Smith, William G. "For Braudel: A Note on the 'École des Annales' and the Historiography of Africa." History in Africa 4 (1977): 275-281.

- Cooper, Frederick. "Decolonizing Situations: The Rise, Fall, and Rise of Colonial Studies, 1951-2001," French Politics, Culture, and Society 20#2 (2002): 47-76.

- Curtin, Philip, et al. African History: From Earliest Times to Independence (2nd ed. 1995), a standard history; 546 pages0

- Curtin, Philip D. African history (1964) 80pp; online

- Engelbrecht, C. "Marx’s Theory of Colonisation and Contemporary Eastern Cape (South Africa) Historiography." (2012) online

- Etherington, Norman. "Recent trends in the historiography of Christianity in Southern Africa." Journal of Southern African Studies 22.2 (1996): 201-219.

- Hetherington, Penelope. "Women in South Africa: the historiography in English." International Journal of African Historical Studies 26.2 (1993): 241-269.

- Hopkins, A. G. "Fifty years of African economic history." Economic History of Developing Regions 34.1 (2019): 1-15.

- Iliffe, John. Africans: The History of a Continent (1995; 3rd ed/ 2017) online, a standard history.

- Ki-Zerbo, Joseph, ed. UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. I, Methodology and African Prehistory (1981), unabridged online 850pp; also abridged edition 368pp (U of California Press, 1981)

- Fage, J. D. "The development of African historiography." pp 25–42

- Curtin, P.D. "Recent trends in African historiography and their contribution to history in general" pp 54–71.

- MacGaffey, Wyatt. "Concepts of race in the historiography of Northeast Africa." Journal of African History (1966): 1-17. online

- Manning, Patrick. "African and world historiography." Journal of African History (2013): 319-330. online

- Martin, William G., William Martin, and Michael Oliver West, eds. Out of one, many Africas: Reconstructing the study and meaning of Africa (U of Illinois Press, 1999).

- Maylam, Paul. South Africa's racial past: The history and historiography of racism, segregation, and apartheid (Routledge, 2017).

- Roberts, A. D. "The Earlier Historiography of Colonial Africa" History in Africa , Vol. 5 (1978), pp. 153–167. online

- Robertshaw, Peter. "Rivals no more: Jan Vansina, precolonial African historiography, and archaeology." History in Africa 45, no. 1 (2018): 145-160.

- Whitehead, Clive. "The historiography of British imperial education policy, Part II: Africa and the rest of the colonial empire." History of Education 34.4 (2005): 441-454. online

- Zewde, Bahru. "African historiography: Past, present and future." Afrika Zamani: revue annuelle d'histoire africaine/Annual Journal of African History 7-8 (2000): 33-40.

- Zimmerman, Andrew. "Africa in imperial and transnational history: Multi-sited historiography and the necessity of theory." Journal of African History (2013): 331-340. online

Regions

- Akyeampong, Emmanuel Kwaku. Themes in West Africa's History (2006) 323pp.

- Burton, Andrew, and Michael Jennings. "Introduction: The emperor's new clothes? Continuities in governance in late colonial and early postcolonial East Africa." International Journal of African Historical Studies 40.1 (2007): 1-25. online

- Borutta, Manuel, and Sakis Gekas. "A colonial sea: The Mediterranean, 1798–1956." European Review of History 19.1 (2012): 1-13' North Africa online

- Cobley, Alan. "Does social history have a future? The ending of apartheid and recent trends in South African historiography." Journal of Southern African Studies 27.3 (2001): 613-625.

- Dueck, Jennifer M. "The Middle East and North Africa in the imperial and post-colonial historiography of France." Historical Journal (2007): 935-949. online

- Dueppen, Stephen A. "The archaeology of West Africa, ca. 800 BCE to 1500 CE." History Compass 14.6 (2016): 247-263.

- Fage, J. D. A Guide to Original Sources for Precolonial Western Africa Published in European Languages (2nd ed. 1994); updated in Stanley B. Alpern, ed. Guide to Original Sources for Precolonial Western Africa (2006).

- Gjersø, Jonas Fossli. "The scramble for East Africa: British motives reconsidered, 1884–95." Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 43.5 (2015): 831-860. online

- Greene, S. E. Sacred Sites and the Colonial Encounter: A History of Meaning and Memory in Ghana (2002)

- Hannaford, Matthew J. "Pre-Colonial South-East Africa: Sources and Prospects for Research in Economic and Social History." Journal of Southern African Studies 44.5 (2018): 771-792. online

- Heckman, Alma Rachel. "Jewish Radicals of Morocco: Case Study for a New Historiography." Jewish Social Studies 23.3 (2018): 67-100. online

- Lemarchand, René. "Reflections on the recent historiography of Eastern Congo." Journal of African History 54.3 (2013): 417-437. online

- Mann, Gregory. "Locating colonial histories: between France and West Africa." American Historical Review 110.2 (2005): 409-434. focus on local memories and memorials online

- Reid, Richard. "Time and distance: Reflections on local and global history from East Africa." Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 29 (2019): 253-272. online

- Reid, Andrew. "Constructing history in Uganda." Journal of African History 57.2 (2016): 195-207. online

- Soares, Benjamin. "The historiography of Islam in West Africa: an anthropologist's view." Journal of African History 55.1 (2014): 27-36. online

- Tonkin, Elizabeth. Narrating our pasts: The social construction of oral history (Cambridge university press, 1995), on West Africa