Adrian Vermeule

Cornelius Adrian Comstock Vermeule (/vərˈmjuːl/,[1] born May 2, 1968) is an American legal scholar, currently a law professor at Harvard Law School. He founded the book review magazine The New Rambler.

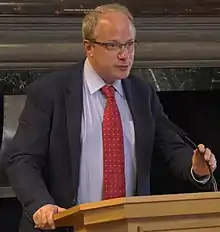

Adrian Vermeule | |

|---|---|

Vermule in 2018 | |

| Born | Cornelius Adrian Comstock Vermeule May 2, 1968 |

| Nationality | American |

| Parent(s) | |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | Law |

| Sub-discipline | |

| Institutions | |

| Website | blogs |

Early life and education

Vermeule was born May 2, 1968, into a family of prominent scholars.[2] His mother, Emily Vermeule, a classical scholar, was the Doris Zemurray Stone Professor at Harvard University. His father, Cornelius Clarkson Vermeule III, served for many years as Curator of the Classical Department at Boston's Museum of Fine Arts. His sister, Blakey Vermeule, is a literary scholar and a Professor of English at Stanford University.

Vermeule graduated from Harvard College (AB, 1990) and Harvard Law School (JD, 1993).

Professional career

Vermeule clerked for Supreme Court Associate Justice Antonin Scalia in 1994 and 1995,[3] and for Judge David Sentelle of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. He joined the faculty of the University of Chicago Law School in 1998 and was twice awarded the Graduating Students' Award for Teaching Excellence (2002, 2004).[4]

Vermeule became professor of law at Harvard Law School in 2006, was named John H. Watson Professor of Law in 2008, and was named Ralph S. Tyler Professor of Constitutional Law in 2016. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2012, at the age of 43.

Vermeule's writings focus on constitutional law, administrative law, and the theory of institutional design. He has authored or co-authored eight books. He teaches administrative law, legislation, and constitutional law.

In 2015, Vermeule co-founded the book review magazine The New Rambler.[5]

On July 24, 2020, Vermeule was appointed to the Administrative Conference of the United States.[6]

Legal philosophy

On judicial interpretation, Vermeule believes:

The central question is not "How, in principle, should a text be interpreted?" The question instead should be, "How should certain institutions, with their distinctive abilities and limitations, interpret certain texts?" My conclusions are that judges acting under uncertainty should strive, above all, to minimize the costs of mistaken decisions and the costs of decision making, and to maximize the predictability of their decisions.[7][4]

Vermeule is a judicial review skeptic. Jonathan Siegel has written that Vermeule's approach to the interpretation of law:

eschews, and attempts to transcend, the main elements of the long-standing debates over methods that courts should use to interpret statutes and the Constitution ... he sees no need to resolve apparently burning questions such as whether courts are bound by what legislatures write, or by what legislatures intend ... For Vermeule, everything comes down to a simple but withering cost–benefit analysis.[8]

In 2007, Vermeule said about the United States Supreme Court that it should stay away from controversial political matters, such as abortion laws and anti-sodomy statutes and defer to Congress, as the elected representatives of the people, except in extremely obvious cases. This would require both liberals and conservative to step back and realize that the benefits of such a court would outweigh the drawbacks for both. Vermeule was thus suggesting "a kind of arms-control agreement, a tacit deal."[9]

Vermeule believes that legal change can only come about through cultural improvements. In an interview in 2016 after his conversion to Catholicism, Vermeule said,

I put little stock or faith in the law. It is a tool that may be put to good uses or bad. In the long run it will be no better than the polity and culture in which it is embedded. If that culture sours and curdles; so will the law; indeed that process is well underway and its tempo is accelerating. Our hope lies elsewhere.[3]

Political views

Integralism

A convert to Catholicism, Vermeule has become an advocate of integralism, a form of modern political thought originating in historically Catholic-dominant societies and opposed to the liberal ideal of division between church and state. Integralism in practice gives rise to state order (identifiable as theocratic) in which a religiously-conceived "Highest Good" has precedence over individual autonomy, the value prioritized by liberal democracy. Rather than electoral politics, the path to confessional political order in integralist theory is “strategic ralliement,” or transformation within institutions and bureaucracies, that lays the groundwork for a realized integralist regime to succeed a liberal democratic order it assumes to be dying. The new state would "exercise coercion over baptized citizens in a manner different from non-baptized citizens".[10][11][12]

To achieve this end, Vermeule has suggested giving confirmed Catholics priority in immigration, allowing them to "jump immediately to the head of the queue". Vermeule describes this as being essential to "the eventual formation of the Empire of Our Lady of Guadalupe, and ultimately the world government required by natural law".[13]

Common-good constitutionalism

In an article in The Atlantic in March 2020, Vermeule suggests that originalism – the idea that the meaning of the American Constitution was fixed at the time of its enactment, which has been the principal legal theory of conservative judges and legal scholars for the past 50 years, but which Vermeule now characterizes as merely "a useful rhetorical and political expedient" – has outlived its usefulness and needs to be replaced by what he calls "common-good constitutionalism". Under this theory of jurisprudence, the moral values of the religious right[14] would be imposed on the American people whether they, as a whole, believe in them or not.[15]

Vermeule's concept of common-good constitutionalism is:

based on the principles that government helps direct persons, associations, and society generally toward the common good, and that strong rule in the interest of attaining the common good is entirely legitimate. ... This approach should take as its starting point substantive moral principles that conduce to the common good, principles that officials (including, but by no means limited to, judges) should read into the majestic generalities and ambiguities of the written Constitution. These principles include respect for the authority of rule and of rulers; respect for the hierarchies needed for society to function; solidarity within and among families, social groups, and workers’ unions, trade associations, and professions; appropriate subsidiarity, or respect for the legitimate roles of public bodies and associations at all levels of government and society; and a candid willingness to "legislate morality –indeed, a recognition that all legislation is necessarily founded on some substantive conception of morality, and that the promotion of morality is a core and legitimate function of authority. Such principles promote the common good and make for a just and well-ordered society.[15]

Vermeule specified that common-good constitutionalism is "not tethered to particular written instruments of civil law or the will of the legislators who created them", so the stated purpose of the legislation is irrelevant to him. Yet he also says that "officials (including, but by no means limited to, judges)" will need "a candid willingness to 'legislate morality'" in order to create a "just and well-ordered society."[15]

The main aim of common-good constitutionalism:

is certainly not to maximize individual autonomy or to minimize the abuse of power (an incoherent goal in any event), but instead to ensure that the ruler has the power needed to rule well ... Just authority in rulers can be exercised for the good of subjects, if necessary even against the subjects’ own perceptions of what is best for them — perceptions that may change over time anyway, as the law teaches, habituates, and re-forms them. Subjects will come to thank the ruler whose legal strictures, possibly experienced at first as coercive, encourage subjects to form more authentic desires for the individual and common goods, better habits, and beliefs that better track and promote communal well-being.[15]

The values which Vermeule believes should be upheld for the good of the "subjects" of the "ruler" include traditional family values, traditional sexual and gender roles, and outlawing abortion.

According to Eric Levitz, the values Vermeule promotes are those of Catholicism and the Christian right.[14] Law professor Randy E. Barnett characterizes Vermeule's essay as "an argument for the temporal power of the state to be subordinated to the spiritual power of the Church."[16] Constitutional law professor Garrett Epps characterizes Vermeule as "an authentic Christian nationalist to whom the Constitution is only an obstacle". Vermeule's common-good constitutionalism argument is, according to Epps, really "authoritarian extremism" which "has absolutely nothing to do with the actual United States Constitution, and in many ways flatly contradicts it. ... In fact, the Constitution as such is not a binding text to Vermeule" since it must be, in Vermeule's words, "read into" in order to arrive at the results he prefers. In the end, Epps criticizes Vermeule's concept as a "banal" anti-constitutional theory akin to Falangism.[17] Levitz notes that Vermeule received little support from conservatives for his arguments, although some did object to characterizing him as "authoritarian".[14][15]

In a column in The Washington Post, prominent conservative George F. Will described Vermeule's "common-good constitutionalism" as "Christian authoritarianism — muscular paternalism, with government enforcing social solidarity for religious reasons. This is the Constitution minus the Framers’ purpose: a regime respectful of individuals’ diverse notions of the life worth living." Will goes on to say about Vermeule's concept and some other contemporary conservative views "...American conservatism, when severed from the Enlightenment and its finest result, the American Founding, becomes spectacularly unreasonable and literally un-American."[18]

Criticism

Elliot Kaufman, writing in the conservative magazine National Review, has described Vermeule as a "reactionary" and an "illiberal" following in the footsteps of German Nazi thinker Carl Schmitt. In Kaufman's view, Vermeule's illiberalism is "dangerous."[19] The American philosopher Brian Leiter has described Vermeule as a "run-of-the-mill legal conservative" who found an intellectual home among other "reactionary Catholics."[20] Fellow law professor Rick Hills has been much harsher in his criticism, describing Vermeule's recent writings as a kind of "anti-liberal chic," or "a really cheap way to signal one’s willingness to offend without putting any specific cards on the table about one’s own specific views about, say, the acceptability of locking up demonstrators who offend the regime in power."[21]

Personal life and views

Vermeule was raised as an Episcopalian, abandoning the denomination in college, but returning to it later in life.[22] He announced his conversion to Catholicism in 2016.[3] He said in an October 2016 interview that the logic behind his Catholic beliefs is inspired by John Henry Newman, and added:

Raised a Protestant, despite all my thrashing and twisting, I eventually couldn't help but believe that the apostolic succession through Peter as the designated leader and primus inter pares is in some logical or theological sense prior to everything else – including even Scripture, whose formation was guided and completed by the apostles and their successors, themselves inspired by the Holy Spirit.[3]

Vermeule sees no viable middle course between atheism and Catholicism.[3]

Works

Books

- Vermeule, Adrian (2006). Judging Under Uncertainty: An Institutional Theory of Legal Interpretation. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Vermeule, Adrian; Posner, Eric (2007). Terror in the Balance: Security, Liberty, and the Courts. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Vermeule, Adrian (2009). Law and the Limits of Reason. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Vermeule, Adrian; Posner, Eric (2010). The Executive Unbound: After the Madisonian Republic. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Vermeule, Adrian (2011). The System of the Constitution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Vermeule, Adrian; Breyer, Stephen G.; Stewart, Richard B.; Sunstein, Cass R.; Herz, Michael (2011). Administrative Law and Regulatory Policy: Problems Text, and Cases (7th ed.). New York: Wolters Kluwer Law & Business. ISBN 9780735587441.

- Vermeule, Adrian (2014). The Constitution of Risk. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sunstein, Cass R.; Vermeule, Adrian (2020). Law & Leviathan: Redeeming the Administrative State. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Journal articles

- Vermeule, Adrian (2007). "Book Review: Instrumentalisms" (PDF). Harvard Law Review. 120: 2113.

- Vermeule, Adrian (2007). "Posner on Security and Liberty: Alliance to End Repression v. City of Chicago" (PDF). Harvard Law Review. 120: 1251.

- Vermeule, Adrian (February 2009). "Our Schmittian Administrative Law" (PDF). Harvard Law Review. 122: 1095.

- Vermeule, Adrian; Sunstein, Cass R. (June 2009). "Conspiracy Theories: Causes and Cures". Journal of Political Philosophy. 17 (2): 202–227. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9760.2008.00325.x.

- Vermeule, Adrian (November 2017). "A Christian Strategy". First Things.

References

- Martin, Douglas (December 9, 2008) "Cornelius C. Vermeule III, a Curator of Classical Antiquities, Is Dead at 83", The New York Times. Retrieved September 8, 2012

- Carter, Jane B. & Morris, Sarah P. (December 18, 2013). The Ages of Homer: A Tribute to Emily Townsend Vermeule. University of Texas Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-292-73376-3.

- Teahan, Madeleine (October 28, 2016). "There is no middle way between atheism and Catholicism, says Harvard professor who is converting". Catholic Herald. Archived from the original on December 15, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- Schuler, Peter (June 10, 2004) "Adrian Vermeule, Professor in the Law School", The University of Chicago Chronicle, v.23, n.18. Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- Kerr, Orin (March 3, 2015). "The New Rambler". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 24, 2016.

- "President Donald J. Trump Announces Intent to Appoint Individuals to Key Administration Posts". The White House. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- Schuler, Peter (June 6, 2002) "Adrian Vermeule, Professor in the Law School", The University of Chicago Chronicle, v.21, n.17. Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- Siegel, Jonathan R. (January 2008) "Judicial Interpretation in the Cost-Benefit Crucible" Minnesota Law Review, v.92, pp.387-88

- Shea, Christopher (October 7, 2007) "Supreme downsizing" The Boston Globe

- Peters, Nathaniel (April 11, 2018) "The Ultimate Catholic Showdown? Liberalism vs. Integralism at Harvard" Public Discourse

- Vermeule, Adrian (March 16, 2018) "Ralliement: Two Distinctions" The Josias

- Beauchamp, Zack (September 9, 2019) "The anti-liberal moment" Vox

- Vermeule, Adrian (July 20, 2019) "A Principle of Immigration Priority" Mirror of Justice

- Levitz, Eric (April 2020) "No, Theocracy and Progressivism Aren’t Equally Authoritarian" New York

- Vermeule, Adrian (March 31, 2020) "Beyond Originalism" The Atlantic Monthly

- Barnett, Randy E. (April 3, 2020) "Common-Good Constitutionalism Reveals the Dangers of Any Non-originalist Approach to the Constitution" The Atlantic Monthly

- Epps, Garrett (April 3, 2020) "Common-Good Constitutionalism Is an Idea as Dangerous as They Come" The Atlantic Monthly

- Will, George F. (May 29. 2020) "When American conservatism becomes un-American" The Washington Post

- Kaufman, Elliot. "Editorship and the Art of Writing". National Review. National Review. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Leiter, Brian. "Catholic jihad". Leiter Reports. Brian Leiter. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Hills, Rick. "Adrian Vermeule's Anti-Liberal Chic?". Pawfsblawg. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Deardurff, Christina (October 2016) "Finding Stable Ground" (interview) Inside the Vatican

External links

- Official website

- Harvard Law School biography

- Chappel, James (Spring 2020). "Nudging Towards Theocracy: Adrian Vermeule's War on Liberalism". Dissent. Retrieved 12 May 2020.