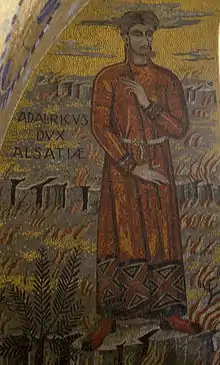

Adalrich, Duke of Alsace

Adalrich (Latin: Adalricus; reconstructed Frankish: *Adalrik; died after c. 683 AD), also known as Eticho,[lower-alpha 1] was the Duke of Alsace, the founder of the family of the Etichonids and of the Habsburg, and an important and influential figure in the power politic of late seventh-century Austrasia.

Adalrich's family originated in the pagus Attoariensis[1] around Dijon in northern Burgundy. In the mid-seventh century they began to be major founders and patrons of monasteries in the region under a duke named Amalgar and his wife Aquilina.[2] They founded a convent at Brégille and an abbey for men at Bèze, installing children in both abbacies. They were succeeded by their third child, Adalrich,[3] who was the father of Adalrich, Duke of Alsace.

Civil war of 675–679

Adalrich first enters history as a member of the faction of nobles which invited Childeric II to take the kingship of Neustria and Burgundy in 673 after the death of Chlothar III. He married Berswinda, a relative of Leodegar, the famous Bishop of Autun, whose party he supported in the civil war which followed Childeric's assassination two years later (675). Adalrich was duke by March 675, when Childeric had granted him honores in Alsace with the title of dux and asked him to transfer some land to the recently founded (c. 662) abbey at Gregoriental[4] on behalf of Abbot Valedio. This grant was most probably the result of his support for Childeric in Burgundy, which had often disputed possession of Alsace with Austrasia. Later writers saw Adalrich as the successor in Alsace of Duke Boniface. After Childeric's assassination, Adalrich threw his support behind Dagobert II for the Austrasian throne.

Adalrich abandoned Leodegar and went over to Ebroin, the mayor of the palace of Neustria, sometime before 677, when he appears as an ally of Theuderic, who granted him the monastery of Bèze.[5] Taking advantage of the assassination of Hector of Provence in 679 to bid for power in Provence, he marched on Lyon but failed to take it and, returning to Alsace, switched his support to the Austrasians once more, only to find himself dispossessed of his lands in Alsace by King Theuderic III, an ally (and puppet) of Ebroin's who had opposed Dagobert in Austrasia since 675, who gave them to the Abbey of Bèze that year (679).

Power in Alsace

Adalrich maintained his power in a restricted dukedom which did not encompass land west of the Vosges as it had under Boniface and his predecessors. This land was a part of the kingdoms of Neustria and Burgundy, and only the land between the Vosges and the Rhine south to the Sornegau, later Alsace proper, remained with Austrasia under Adalrich. The west of Vosges was under duke Theotchar.

In Alsace, however, the civil war had resulted in a curtailed royal power and Adalrich's influence and authority, though restricted in territory, was augmented in practical scope. After the war, parts of the Frankish kingdom saw a more powerful viceregal hand under the exercise of the mayors of the palaces, while other regions were even less directly affected by the royal prerogative. The Merovingian palace at Marlenheim in Alsace was never visited by a royal figure again in Adalrich's lifetime. While southern Austrasia had been the centre of Wulfoald's power, the Arnulflings were a north Austrasian family, who took scarce interest in Alsatian affairs until the 730s and 740s.

Adalrich had initially made his allies counts, but in 683 he granted the comital office to his son and eventual successor Adalbert. By controlling monasteries and counties in the family, Adalrich built up a powerful regional duchy to pass on to his Etichonid heirs.

Relationship with monasteries

Adalrich had a rocky relationship with the monasteries of his realm, upon which he relied for his power. He is infamous for the suppression of that of Moutier-Grandval, and for lording it over monasteries, including his own foundations. According to the Life of Germanus of Grandval, Adalrich "wickedly began oppressing the people in the vicinity [Sornegau] of the monastery and to allege that they had always been rebels against his predecessors." He removed the centenarius ruling in the region and replaced him with his own man, Count Ericho. He exiled the people of the Sornegau, who denied being rebels against previous dukes. Many of the people exiled from the valley were attached to Grandval and could not thus be exiled. Adalrich marched into the valley of the Sornegau with a large army of Alemanni at one end while his lieutenant Adalmund entered with a host by the other. The abbot, Germanus himself, and his provost Randoald met Adalrich with books and relics in order to persuade him not to make violence. The duke granted a wadium,[6] a device of recompense or promise, and offered thus to spare the valley devastation, but for unknown reasons Germanus refused it. The region was ravaged.

Perhaps as penance for his relationship to the deaths of two future saints, Leodegar and Germanus of Grandval, or perhaps out of a secret desire — disclosed it is said to his intimate friends — to found a place to the service of God and take up the religious life, Adalrich founded two monasteries in north central Alsace between 680 and 700: Ebersheim in honour of Saint Maurice and Hohenburg on the site of an old Roman fort (of the emperor Maximian) discovered by his huntsmen and which he appropriated for his own military uses. Adalrich's daughter Odilia served as Hohenburg's first abbess and was later named patron saint of Alsace by Pope Pius VII in 1807.

Veneration as a saint

His daughter Odilia was reputedly born blind, which Adalrich took as a punishment for some offence done to God. In order to save face with his retainers, he tried to persuade his wife to kill the infant child in secret. Bereswinda instead sent the child into hiding with a maid at the monastery of Palma. According to the Life of Odilia, a bishop named Erhard baptised the adolescent girl and smeared a chrism on her eyes, which miraculously restored her sight.

The bishop tried to restore the duke's relationship with his daughter, but Adalrich, fearing the effect of admitting to having a daughter hiding in poverty in a monastery would have on his subjects, refused. A son of his, ignoring Adalrich's orders, brought his sister back to Hohenburg, where Adalrich was holding court. When Odilia arrived, Adalrich, in a rage, struck a blow with his sceptre to his son's head, accidentally killing him. Disgraced, he reluctantly allowed Odilia to live in the monastery, which had no abbess, with a minimal wage under a British nun.

Towards the end of his life he was reconciled to her and made her the first abbess of his foundation, handing the abbey over as if it were private property.[7] Through his daughter Adalrich was reconciled to God and as early as the twelfth century was regarded as a saint with a local cult. His burial garments were displayed to pilgrims in his foundation at Hohenburg and a feast day was celebrated annually by the nuns. The portrayal of Adalrich as a nobleman who became holy while retaining his noble status and rank was very popular in the Rhineland and as far away as Bavaria in the Middle Ages. The Life probably sought to show how by simply maltreating a blind daughter in order to save face, Adalrich ended up far more dishonoured than he otherwise would have.

Notes

- His name is also given as Adalricus, Chadelricho, Hetticho, Etichon, Cathicus, Cathic, or Athich.

References

- The placename survived in the ninth-century title of Isembard, comte d'Attuyer/Atuyer son of Adalard, comte de Chalon. ("Les comtes de Chalon-sur-Saône").

- The duke Amalgar and his wife Aquilina, said to be the daughter of Waldelenus, dux in the region between the Alps and the Jura, and Flavia, feature in a reconstructed genealogy linking the Etichonids of Alsace with a Gallo-Roman ancestry through Flavia, were noted in Christian Settipani, "La transition entre mythe et réalité", Archivum 37 (1992:27-67); Settipani speculates on Flavia's connections with Felix Ennodius and Syagria.

- He is referred to as Liutheric, a mayor of the palace, in the Life of Odilia.

- For this Münster im St. Gregoriental, still at this time under its original Rule of St. Columbanus, see Marmoutiers Abbey, Alsace.

- According to its chronicler Johannes of Bèze, the monastery of Fons Besua had been founded on a royal grant of land from Dagobert I (628) by Amalgar: see Waldalenus

- "Vadium"

- Hans Hummer, "Reform and lordship in Alsace at the turn of the millennium," in Warren Brown and Piotr Górecki, eds. Conflict in Medieval Europe: Changing Perspectives on Society and Culture (Ashgate) 2003:76.

Sources

- Hummer, Hans J. Politics and Power in Early Medieval Europe: Alsace and the Frankish Realm 600 – 1000. Cambridge University Press: 2005. See mainly pp 46–55.

- Lewis, Archibald Ross. "The Dukes in the Regnum Francorum, A.D. 550-751." Speculum, Vol. LI, No. 3. July, 1976. pp 381–410.