Aboriginal tracker

Aboriginal trackers were enlisted by Europeans in the years following British colonisation of Australia, to assist them in exploring the Australian landscape. The excellent tracking skills of these Aboriginal Australians were advantageous to settlers in finding food and water and locating missing persons, capturing bushrangers and violently "dispersing" other groups of Indigenous peoples.

The first recorded deployment of Aboriginal trackers by Europeans in Australia was in 1791 when Watkin Tench utilised Eora men Colbee and Balloderry to find a way to the Hawkesbury River.[1] In 1795, an aboriginal guide led Henry Hacking to the Cowpastures area where the lost First Fleet cattle were found.[2] In 1802, Dharawal men Gogy, Budbury and Le Tonsure with Gandangara men Wooglemai and Bungin assisted Ensign Francis Barrallier in his explorations into the Blue Mountains.[3] There are many other examples of explorers, squatters, military/paramilitary groups, naval missions, and police utilising Aboriginal assistance in tracking down wanted persons. For instance, in 1834, near Fremantle, Western Australia, two trackers named Mogo and Mollydobbin tracked a missing five-year-old boy for more than ten hours through rough Australian bush.[4] Another notable event occurred in 1864 when Duff children Jane (7), Isaac (9) and Frank (4) Duff, lost for nine days in Wimmera, were found by Aboriginal tracker Dick-a-Dick.[4][5]

Tracking

When asked how he tracked, Mitamirri, a famous tracker of the early 20th century, said "I never bend down low, just walk slow round and round until I see more."[6]

In 1845 Edward Stone Parker the Assistant Protector of Aborigines in Victoria, based at the Loddon Aboriginal Protectorate Station at Franklinford, wrote a letter to the Chief Protector reporting on the murder of 'a native' at Joyce's Station (near Newstead). No witness to the murder could be found but footprints of five men were tracked by the Jajowurrong to open country south of Mount Macedon (Sunbury region). The trackers there met with another man attached to the Loddon Protectorate Station who was on his return from Melbourne. He told the trackers he had met with the group they were tracking and was able to give a description of them.[7]

The New South Wales Police Force actively engaged Aboriginal trackers from 1850, attempting to secure Aboriginal trackers for each of the police districts. By 1867, 52 Aboriginal Trackers were in the employ of the police at a daily rate of 2s 6d (approximately £3/17/6 per month).[8] In that year, at the height of bushranger activity in the Goulburn Police District, three mounted Aboriginal trackers of the New South Wales Police Force were actively involved in the capture of the Clarke brothers at Jinden near Braidwood. Aboriginal tracker Sir Watkin Wynne (later Sergeant Major Sir Watkin Wynne), led the initial party of police from Fairfield under the command of Senior Constable Wright (later Sub-inspector Wright) to their location at Jinden. He was seriously injured during the capture and had an arm amputated. He was awarded £120 for his role in the capture. Two other trackers, who subsequently led other police to the scene, trackers George Emmott (stationed at Ballalaba) and Thomas (stationed at Major's Creek), secured lesser awards of £7/10/0. Tracker George Emmott had previously received an award of £30 for the arrest of Pat Connell another member of the gang.[9]

Two members of the Queensland Native Mounted Police Force, Wannamutta and Werannabe, assisted in the capture of Ned Kelly at Glenrowan, Victoria in 1880. They had been promised £50 reward for Kelly's capture but descendants claimed the two were never paid.[10]

Native Police

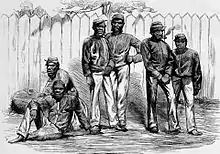

A number of Native Police organisations were established in Australia during the 19th Century employing armed and mounted Aboriginal trackers under white officers to carry out various duties, the foremost of these being punitive missions against Aboriginal peoples who resisted colonialisation.[11] During the goldrush era, they were also used to patrol goldfields and search for escaped prisoners.[12] They were provided with uniforms, firearms, food rations and a dubious salary.[13]

In 1879 the services of a group of Queensland Aboriginal police were requested to help track the Kelly gang which were on the run from the Victorian police. Their use was agreed and a party of six "native" troopers, with a white officer (Sub-Inspector Stanhope O'Conner) reached Benalla about March 1879.[14]

Recent and present day use

In 1941, the Northern Territory Special Reconnaissance Unit was established to patrol the north Australia coastline for Japanese landings and infiltration, and was primarily composed of Aboriginal soldiers. The 2/1st North Australia Observer Unit ("Nackaroos") performed a similar role, though Aboriginal people were a minority in the unit, serving as labourers and trackers.[15]

In the present day Australian Army, the Regional Force Surveillance Units can be seen as a spiritual descendant of the tracker legacy.

Aboriginal trackers within the Queensland police force wore yellow epaulets to denote their role. Australia's last Aboriginal police tracker employed solely for the role, Lama Lama elder Barry Port, retired in 2014[16] with no replacement.[17] Port died at Coen on the Cape York Peninsula on 4 March 2020. He had spent 30 years as a tracker, and the public bar at Coen was named after him.[18]

Notable Aboriginal trackers

- Charley

- Dick-a-Dick

- Jimmy Governor

- Jimmy James

- Tommy Windich

- Whyman McLean

- Brownie Doolan (c.1918-2011, worked with police at Finke and Kulgera in Northern Territory)

- Willie Wondunna (c. 1836 – 30 September 1946) of Fraser Island[19]

- Barry Port, Australia's last tracker employed solely for the role, died 2020[18]

Aboriginal trackers in books and film

- Australia

- The Last Trackers of the Outback (2007 documentary film)

- The Nightingale

- The Tracker

- Rabbit-Proof Fence

- A Cry in the Dark

- One Night the Moon

- Black Tracker

- Walkabout (novel)

- The Black Tracker - Jack Davis (1970 Poem)

- No Sugar - Jack Davis (1986)

See also

References

- Tench, Watkin (1793). A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson. London.

- Turbet, Peter (2011). The First Frontier. Rosenburg.

- Barrallier, Francis. Journal.

- "Aboriginal trackers". Department of Culture and Recreation (Government of Australia). Archived from the original on 27 August 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- "Lost in bush for nine days". The Advertiser. Adelaide, South Australia: National Library of Australia. 21 January 1932. p. 8. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- Edgar, S. (1996) "James, Jimmy [Mitamirri] (1902? - 1945)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 14, Melbourne University Press, Parkville.

- Morrison, Edgar (1967). Frontier Life in the Loddon Protectorate. Daylesford: Daylesford Advocate. p. 62.

- NSW State Archives, NRS 10946, Police salary registers

- Martin Brennan's handwritten Police History of Notorious Bushrangers held by the Mitchell Library, Sydney, NSW - A2030 pp270-322, transcribed at http://grafton.nsw.free.fr/mother/pdfs/Brennan.pdf Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Koori Mail, "Tracker descendants to appeal back-pay ruling", 24 September 1997, p. 2.

- Bottoms, Timothy (2013). Conspiracy of Silence. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

- "Large variety of duties - Tracking the Native Police (Public Record Office Victoria)". www.prov.vic.gov.au. Archived from the original on 9 September 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- Skinner, L.E. (1975). Police of the Pastoral Frontier. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

- Sadleir, John (1973). Recollections of a Victorian Police Officer. Blackburn, Victoria: Penguin Colonial Facsimiles. p. 210.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Kim, Sharnie (2 July 2014). "Cape York Aboriginal police tracker Barry Port retiring". Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- Michael, Peter. "Hunt for missing miner Bruce Schuler ends era of trackers". news.com.au. News Limited. Archived from the original on 20 July 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- Sexton-McGrath, Kristy (6 March 2020). "Last Aboriginal police tracker and Cape York legend dies". ABC News. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- "Letters to the Editor". The Telegraph (Brisbane). Queensland, Australia. 28 October 1946. p. 2. Retrieved 11 September 2019 – via National Library of Australia.