Abbas Amir-Entezam

Abbas Amir-Entezam (Persian: عباس امیرانتظام, 18 August 1932 – 12 July 2018) was an Iranian politician who served as deputy prime minister in the Interim Cabinet of Mehdi Bazargan in 1979. In 1981 he was sentenced to life imprisonment on charges of spying for the U.S., a charge critics suggest was a cover for retaliation against his early opposition to theocratic government in Iran. He was "the longest-held political prisoner in the Islamic Republic of Iran".[1] According to Fariba Amini, as of 2006 he had "been in jail for 17 years and in and out of jail for the last ten years, altogether for 27 years."[2]

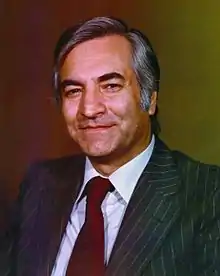

Abbas Amir-Entezam | |

|---|---|

Amir-Entezam in 1979 | |

| Deputy Prime Minister of Iran for Public Relations and Administration | |

| In office 13 February 1979 – August 1979 | |

| Prime Minister | Mehdi Bazargan |

| Succeeded by | Sadeq Tabatabaei |

| Ambassador to Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Norway and Iceland | |

| In office August 1979 – 19 December 1979 | |

| Prime Minister | Mehdi Bazargan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 August 1932 Tehran, Iran |

| Died | 12 July 2018 (aged 85) Tehran, Iran |

| Political party | Freedom Movement of Iran National Front of Iran |

| Spouse(s) | Elaheh Amir-Entezam |

| Children | 3 |

| Website | Official website |

Early life and education

Entezam was born into a middle-class family in Tehran in 1932.[3][4] He studied electro mechanical engineering at University of Tehran and graduated in 1955.[2]

In 1956, Entezam left Iran for study at A.S.T.E.F. Institute (Paris).[2] He then went to the U.S. and completed his postgraduate education at the University of California in Berkeley.[2]

Career

After graduation, he remained in the US and worked as an entrepreneur.[5]

Around 1970 Entezam's mother was dying and he returned to Iran to be with her. Because of his earlier political activities, the Shah's Intelligence Service would not allow him to return to the U.S. He stayed in Iran, marrying, becoming a father and developing a business in partnership with his friend and mentor, Mehdi Bazargan. Bazargan appointed him as the head of the political bureau of the Freedom Movement of Iran in December 1978, replacing Mohammad Tavasoli.[6] In 1979, the Shah was overthrown by the Iranian Revolution. Revolutionary leader Ayatollah Khomeini, recently returned to Iran, appointed Bazargan as prime minister of the provisional revolutionary government. "Bazargan asks Entezam to be the deputy prime minister and the official spokesperson for the new government."[5]

According to Entezam's website:

Following the orders of the Prime Minister, Entezam sets out to rebuild the relationship between the US and the post-revolutionary Iran. He retains diplomatic contacts with the US embassy, advocating for normalization of the relationship between the two countries.[5]

While serving as deputy prime minister in April 1979 Entezam actively advocated the retirement of army officers from the rank of brigadier general.[7] In 1979, Entezam "succeeded in having the majority of the cabinet sign a letter opposing the Assembly of Experts", which was drawing up the new theocratic constitution where democratic bodies were subordinant to clerical bodies. His theocratic opponents attacked him[1] and in August 1979 Bazargan "appointed Entezam to become Iran's ambassador to Denmark."[5]

Imprisonment

In December 1979 Bazargan asked Entezam, who had been serving as ambassador to Sweden, to come back quickly to Tehran.[2] Upon returning to Tehran, he was arrested[2] because of allegations based on some documents retrieved from the U.S. embassy takeover, and imprisoned for a life term. He was released in 1998 but in less than 3 months,[8] he was rearrested because of an interview with Tous daily newspaper, one of the reformist newspapers of the time.

In smuggled letters, Entezam related that on three separate occasions, he had been blindfolded and taken to the execution chamber - once being kept "there two full days while the Imam contemplated his death warrant." He spent 555 days in solitary confinement, and in cells so "overcrowded that inmates took turns sleeping on the floor - each person rationed to three hours of sleep every 24 hours." During his imprisonment, Entezam experienced permanent ear damage, developed spinal deformities, and suffered from various skin disorders."[9]

Death

Entezam died of a heart attack in Tehran on 12 July 2018. He was buried the following day in Behesht e Zahra cemetery, with Ayatollah Montazeri's son leading the funeral prayer.[10]

Awards and honors

- Bruno Kreisky Prize (1998)

- Jan Karski Award for Moral Courage (2003)

See also

References

- Burning candle. Honoring Abbas Amir-Entezam on the 25th anniversary of his arrest Iranian, Masoud Kazemzadeh, 21 December 2004

- Amini, Fariba (24 February 2006). "Perseverance and honor: Interview with Abbas Amir-Entezam". Payvand. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- Kadivar, Darius (19 September 2010). "Abbas Amir Entezam IRI's First Ambassador to Sweden (1979)". Iranian. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- John H. Lorentz (2010). The A to Z of Iran. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-8108-7638-5.

- The official web site of Mr. Entezam Archived 7 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine click on Biography

- http://www2.tulane.edu/liberal-arts/political-science/upload/gasioroski-MEJfall2012.pdf

- Roberts, Mark (January 1996). "Purge of the Monarchists". McNair Papers (47–48). Retrieved 29 August 2013. – via Questia (subscription required)

- E. P. Rakel (2008). "Factional rivalries and Iranian foreign policy". The Iranian political elite, state and society relations, and foreign relations since the Islamic revolution. University of Amsterdam. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- Tortured Confessions: Prisons and Public Recantations in Modern Iran Ervand Abrahamian, University of California Press, 1999, p. 140

- BBC Persian (13 February 2018). "Funeral ceremony of Abbas Amir Entezam was held at Behesht-e-Zahra (in Persian)". Retrieved 15 July 2018.

External links

- Time: Stalking the Conspirators, 28 July 1980

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Mohammad Tavasoli |

Head of Political Bureau of the Freedom Movement of Iran 1978–1979 |

Succeeded by Ebrahim Yazdi |