29P/Schwassmann–Wachmann

Comet 29P/Schwassmann–Wachmann, also known as Schwassmann–Wachmann 1, was discovered on November 15, 1927, by Arnold Schwassmann and Arno Arthur Wachmann at the Hamburg Observatory in Bergedorf, Germany.[5] It was discovered photographically, when the comet was in outburst and the magnitude was about 13.[5] Precovery images of the comet from March 4, 1902, were found in 1931 and showed the comet at 12th magnitude.[5]

| |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Arnold Schwassmann Arno Arthur Wachmann |

| Discovery date | November 15, 1927 |

| Alternative designations | 1908 IV; 1927 II; 1941 VI; 1957 IV; 1974 II; 1989 XV; |

| Orbital characteristics A | |

| Epoch | March 6, 2006 |

| Aphelion | 6.25 AU |

| Perihelion | 5.722 AU |

| Semi-major axis | 5.986 AU |

| Eccentricity | 0.0441 |

| Orbital period | 14.65 a |

| Inclination | 9.3903° |

| Dimensions | 60.4 ± 7.4 km[1] |

| Last perihelion | March 7, 2019[2] |

| Next perihelion | October 31, 2033[3][4] |

The comet is unusual in that while normally hovering at around 16th magnitude, it suddenly undergoes an outburst. This causes the comet to brighten by 1 to 5 magnitudes.[6] This happens with a frequency of 7.3 outbursts per year,[6] fading within a week or two. The magnitude of the comet has been known to vary from 18th magnitude to 10th magnitude, a more than thousand-fold increase in brightness, during its brightest outbursts. On 14 January 2021, an outburst was observed with brightness from 16.6 to 15.0 magnitude, and consistent with the 7.3 outbursts per year noted earlier.[7] Outbursts are very sudden, rising to maximum in about 2 hours, which is indicative of their cryovolcanic origin; and with the times of outburst modulated by an underlying 57-day periodicity possibly suggesting that its large nucleus is an extremely slow rotator.[8]

The comet is a member of a relatively new class of objects called "Centaurs", of which at least 500 are known.[9] These are small icy bodies with orbits between those of Jupiter and Neptune. Astronomers believe that Centaurs have been recently perturbed inward from the Kuiper belt, a disk of Trans-Neptunian Objects occupying a region extending from the orbit of Neptune to approximately 50 AU from the Sun. Frequent perturbations by Jupiter[10] will likely accumulate and cause the comet to migrate either inward or outward by the year 4000.[11]

The dust and gas comprising the comet's nucleus is part of the same primordial materials from which the Sun and planets were formed billions of years ago. The complex carbon-rich molecules they contain may have provided some of the raw materials from which life originated on Earth.

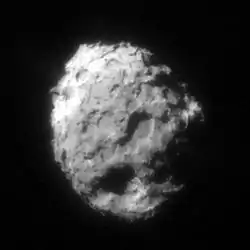

The comet nucleus is estimated to be 60.4±7.4 kilometers[1] in diameter.[10]

29P reached perihelion on March 7, 2019 and has just come to opposition on November 6, 2020.

References

- Schambeau, C.; Fernández, Y.; Lisse, C.; Samarasinha, N.; Woodney, L. (2015). "A new analysis of Spitzer observations of Comet 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1". Icarus. 260: 60–72. arXiv:1506.07037. Bibcode:2015Icar..260...60S. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2015.06.038.

- 29P past, present and future orbital elements

- Syuichi Nakano (January 29, 2012). "29P/Schwassmann-Wachman 1 (NK 2189)". OAA Computing and Minor Planet Sections. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- Patrick Rocher (February 4, 2012). "Note number : 0015 P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1 : 29P". Institut de mécanique céleste et de calcul des éphémérides. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- Kronk, Gary W. (2001–2005). "29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1". Archived from the original on October 22, 2008. Retrieved October 13, 2008. (Cometography Home Page)

- Trigo-Rodríguez; Melendo; García-Hernández; Davidsson; Sánchez (2008). "A continuous follow-up of Centaurs, and dormant comets: looking for cometary activity" (PDF). European Planetary Science Congress. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- Lin, Zhong-Yi; et al. (January 15, 2021). "ATel #14323: Outburst of comet 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1". The Astronomer's Telegram. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- Miles, Richard (July 1, 2016). "Discrete sources of cryovolcanism on the nucleus of Comet 29P/Schwassmann–Wachmann and their origin". Icarus. 272: 387–413. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2015.11.011.

- "JPL Small-Body Database Search: orbital class (CEN)". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- "JPL Close-Approach Data: 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1" (last observation: April 10, 2009). Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- "Twelve clones of 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann diverging by the year 4000". Archived from the original on June 23, 2015. Retrieved April 30, 2009. (Solex 10) Archived December 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Trigo-Rodriguez et al., Outburst activity in comets, I. Continuous monitoring of comet 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1

- Trigo-Rodriguez et al., Outburst activity in comets , II. A multi-band photometric monitoring of comet 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1 arXiv:1009.2381

External links

- Orbital simulation from JPL (Java) / Ephemeris

- 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1 – Seiichi Yoshida @ aerith.net

- 29P monitoring campaign - British Astronomical Association COMET MISSION 29P website

- 29P at CometBase

- 29P at Las Cumbres Observatory (8 Feb 2010 12:23, 60 seconds)

- 29P (Joseph Brimacombe April 18, 2013)

| Numbered comets | ||

|---|---|---|

| Previous 28P/Neujmin |

29P/Schwassmann–Wachmann | Next 30P/Reinmuth |