18th Infantry Regiment (Imperial Japanese Army)

The IJA Eighteenth Infantry Regiment (第18連隊, 歩兵第十八聯隊) Hohei Dai-Ju-hachi Rentai was an infantry regiment in the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA). Its call sign and unit code was Thunder-3219 (雷3219, Kaminari-San-Ni-Ichi-Kyu).[1] The unit was formed in 1884 and based in the city of Toyohashi as a branch of the Nagoya Garrison. Throughout its history, the majority of its soldiers came from the Mikawa region, or eastern Aichi prefecture.

| 18th Infantry Regiment 歩兵第十八聯隊 | |

|---|---|

The 18th Infantry at the battle for Dachang, China, 1937. | |

| Active | 1884–1944 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Garrison/HQ | Nagoya Toyohashi, Japan |

| Engagements | First Sino-Japanese War Russo-Japanese War Jinan Incident Operation Nekka Pacification of Manchukuo Second Sino-Japanese War Marianas Campaign |

The regiment first deployed for the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894. In 1904, it deployed again for the Russo-Japanese War where it fought in several major battles. Between 1928 and 1936, the regiment was deployed to China where it engaged in two military operations in China, though it spent most of the time on garrison and occupation duty.

With the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War in the summer of 1937, the regiment participated in the Battle of Shanghai and then participated in the major campaigns of central China. In 1944, the 18th Regiment was sent to the Pacific theater as part of the 29th Division. On the way to Saipan, the transport ship that was carrying the regiment, the Sakito Maru, was torpedoed and sunk. Over half the regiment drowned, but survivors were rescued and delivered to Saipan. Some stragglers had to be left behind, but the majority of the regiment was sent to Guam and prepared to repel the American invasion. Members of the 18th Regiment participated in both the Battle of Saipan and the Battle of Guam. In both battles, nearly all soldiers of the 18th Regiment were killed in action. A few soldiers survived the massed banzai charges and attempted to evade capture by hiding in the jungles, but as an organization the regiment became defunct and the ranks were not replenished.

After the battle on Saipan, one officer of the regiment, Captain Sakae Ōba, distinguished himself when he took command of some soldiers and assumed responsibility for the civilians who had survived the battle. Ōba and his men surrendered in December 1945, three months after the official end of World War II.

Early history

The three battalions of the 18th Infantry Regiment were established in Nagoya, Japan, and granted their colors on 15 August 1884.[1] By 1886 the regiment had transferred its headquarters to Toyohashi city, and thereafter the majority of its recruits came from that city and the surrounding Mikawa region of eastern Aichi Prefecture.[2] In May 1888, the IJA 3rd Division was organized and the 18th Infantry Regiment was placed in its command.[3]

The regiment deployed for the first time in 1894 to participate in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895). In 1904, the regiment deployed again for the Russo-Japanese War. The regiment saw combat at the Battles of Nanshan, Te-Li-Ssu, Tashihchiao, Shaho, Panlongshan, and other places.[1][4]

In 1907 the regiment was transferred from the 3rd Division to the IJA 15th Division.[3] In 1925, the 15th Division was disbanded by order of War Minister Ugaki Kazushige, and the regiment was returned to the 3rd Division.[3][4]

In May 1928, the regiment deployed for the Jinan Incident,[5] and afterward served as the garrison for Tianjin, China.[1] In February 1933 the regiment participated in Operation Nekka.[1] As a result of this early clash between Chinese and Japanese forces, Inner Mongolia was placed in the Japanese controlled state of Manchukuo.[4][6] In 1934, the regiment was on garrison duty in Manchukuo. The regiment returned to Toyohashi, Japan in 1936.[2][3]

Second Sino-Japanese War

With the outbreak of war following the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, the 18th Regiment was ordered to mobilize in August 1937.[1] The regiment landed and participated in the Battle of Shanghai, then continued on to assist with the Battle of Nanjing.[1][6][7] In early December, the regiment crossed the Yangtze at a point about halfway between Shanghai and Nanjing, launching an attack from Jiangyin on the south bank to Jingjiang on the opposite bank. The regiment occupied the two towns until 9 March 1938.

In May 1938, the regiment participated in the Battle of Xuzhou. Later that year, the regiment participated in the Hankou Operation as part of the larger Battle of Wuhan.[7] In 1939, it fought the Battle of the Xiang River, the First Battle of Changsha, as well as smaller actions in the area.[1][6] In 1940, the 18th Regiment participated in the Ichang Operation and the Han River Operation, both in Hubei Province.[7]

In July 1942, command of the 18th Regiment was transferred from the 3rd Division to the IJA 29th Division.[3] The regiment was then ordered to serve as the garrison force at Haicheng, at the time in Mukden Province, now part of Liaoning Province.[1] By early 1944, much of northern China was nominally secure, and many units were being transferred to various islands in the Pacific in order to support the strained and hyperextended line of defensive positions.[8] By February 1944, the 29th Division, which consisted of the 18th, the 38th, and the 50th Infantry Regiments, was ordered to mobilize and prepare for operations in the Pacific.[1][8]

Pacific Theater

From Manchuria, the 18th Infantry Regiment and its sister regiments travelled to Korea, where they embarked on four transport vessels at Pusan.[9] The convoy was escorted by three Yugumo-class destroyers of Destroyer Division 31: Asashimo, Kishinami, and Okinami, and were first sent to the Japanese-held island of Saipan.[10][11][12] On 29 February 1944 the transport ship carrying the regiment, the Sakito Maru, was hit by a torpedo fired from the USS Trout (SS-202), an American submarine, just northeast of Saipan.[8][9] The transport sunk, taking with it 2,200 of the 3,500 men on board, which included the regimental commander, Colonel Monma Kentaro.[13][14] Also lost on the transport were several tanks and most of the regiment's equipment.[6] The convoy's three escort destroyers dropped depth charges, sank the Trout, and then rescued the survivors of the sunken transport. About 1,800 troops of the regiment were delivered to Saipan.[13]

Saipan

After re-organization, two battalions of the under-equipped 18th Regiment were transported to Guam in May 1944;[7][9] however, about 600 troops of the 1st Battalion had to be left behind on Saipan. These troops, under Captain Masao Kubo, joined the island's garrison,[15] though nearly all would be killed during the Battle of Saipan in June and July 1944.[9] In the aftermath of the battle, Capt. Sakae Ōba distinguished himself by taking command of a number of soldiers and sailors who had survived the battle, as well as Japanese civilians who looked to him for guidance and protection. The group numbered about 300, and took shelter in caves or small villages in the jungle. They evaded capture by the U.S. Marines that were hunting for them, conducted harassment raids, and survived until they finally agreed to surrender on 1 December 1945.[16]

Guam

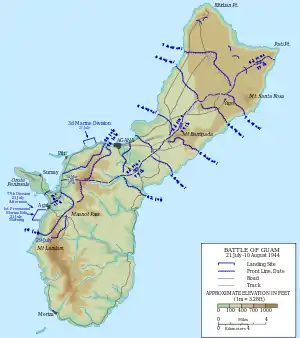

In March 1944, the 29th Division commander, Lieutenant General Takeshi Takashina, landed on Guam and assumed overall command of all military units for the island's defense.[13] In preparation for the imminent invasion of Guam by Allied forces, the main body of the 18th Regiment was situated on a mountain, with each company deployed to cover possible landing points in support of the island's defensive strategy.[2] On 21 July 1944 the American landing operation commenced.[17] Despite fierce resistance, United States Army and Marine forces gained two beachheads by nightfall, straddling the Orote Peninsula on the west coast of the island, while the defenders either counterattacked or continued to fire on American positions with machine guns, artillery, and mortars.[18]

On 24 July, the command headquarters of the Japanese forces on Guam received word from Tokyo to "Defend Guam at all costs".[19] General Takashina devised a plan of attack to dislodge the 3rd Marine Division, which occupied the high ground at Asan, north of the Orote Peninsula. Takashina's attack would be coordinated with a breakout attempt of Japanese forces trapped on the peninsula.[19] The 18th Regiment, which had been reorganized into three battalions, was to be one of the main units to assault the American position. Two battalions would attack the 21st Marine Regiment and the other battalion was to attack the flank of the 9th Marines. The objective was to exploit an 800-yard gap between the two regiments, break through the American lines, and attain the high ground. Other units would attack the Marines or head to the beaches with demolition charges to destroy any ammunition or supply caches left by American forces.[20]

On the night of 25 July, the colors of the 18th Infantry Regiment were ritually burned, by authorization of the division commander, in anticipation of the regiment's complete destruction.[6]

First Battalion

Just after midnight, the 1st Battalion, 18th Regiment, attacked the center of the 22nd Marines. Veterans of the battle later reported that while many of the Japanese soldiers carried rifles and their officers led with swords, some of the Japanese carried knives, pitchforks, or their bayonets mounted to long sticks and used as spears. Charging across open ground, they were hit by American artillery, mortars, and machine gun fire until they retreated into a mangrove swamp. Artillery continued to bombard the swamps, discouraging further attack from that approach.[21]

Second Battalion

The Japanese main attack was launched at about 0300, 26 July. The assault of the 2nd Battalion, 18th Regiment, under Major Maruyama Chusa, struck the center of the 21st Marines, and was the scene of some of the most desperate hand-to-hand combat of the entire night.[22] The battalion charged through machine gun and artillery fire in an effort to reach the Marines. In an effort to break through the lines, Maruyama's men fought their way into a draw that led down to the beach. The Marines had prepared for that possibility, and once in the draw the Japanese faced several Sherman tanks. Lacking any sort of anti-tank weaponry, the Japanese troops were unable to damage a single tank, and flowing over and past them, continued on down the draw. Those troops who were unable to reach the draw regrouped and charged another point in the Marine line and fought hand-to-hand until their numbers became depleted.[23]

Third Battalion

The 3rd Battalion of the 18th Regiment, led by Major Yukioka Setsuo, was able to exploit a gap between the lines of the 9th and the 21st Marines, and drove hard toward the Marines' regimental Command Post (CP) near the beach. The Japanese came close to overrunning the CP, but Yukioka's attack was blunted by desperate fighting during the Marines' counterattack supported by artillery and mortars. One element of the 3rd Battalion encountered and attacked the 3rd Marine Division Headquarters area. The Japanese were prevented from overrunning the position only when every available Marine, including cooks, clerks, doctors, and some of the wounded, joined the fighting, before two companies of combat engineers arrived to support the defenders. The engineers counterattacked, and by dawn the Japanese troops were dead or scattered;[24] many fled up the Nidual River valley. The Engineers pursued, and over the course of the day reported witnessing many of the Japanese committing suicide by an unprecedented method: when a Japanese soldier had given up on escape, and capture seemed imminent, he pulled the pin of his grenade, placed it on top of his head, then held his helmet down over the grenade and waited for the inevitable.[25]

By the morning of 26 July, it was apparent that the attack to dislodge the American position had failed, as had the breakout attempt at Orote Peninsula.[26] It was also apparent to General Takashina that victory at Guam would be impossible, due to enormous losses in personnel, leadership, weapons, and morale. Takashina decided that all remaining troops should escape to the interior of the island, in order to regroup, and carry on a guerrilla campaign to inflict as much damage as possible on the American forces.[14] During the previous night's fighting, most of the men of the 18th Regiment had been killed in action,[1] along with their commanding officer, Colonel Hikoshiro Ohashi.[27] By the end of 26 July 1944, the 18th Infantry Regiment had ceased to be a functioning unit.[1][2]

Memorialization

The main memorial for the 18th Infantry Regiment is located in Toyohashi City Park.[28] There are also monuments on the islands of Saipan and Guam, paid for by the regimental veterans' association.[29][30]

See also

- 18th Independent Mixed Brigade

- Battle of Guam (1944)

- Imperial Japanese Army Uniforms

- Japanese holdout

- List of Japanese Infantry divisions

- List of Japanese military equipment of World War II

- Organization of the Imperial Japanese Army

- Rank insignia of the Imperial Japanese Army

- Second Sino-Japanese War

References

- 日本陸軍連隊総覧 歩兵編 [Survey of the Regiments of the Japanese Army: Infantry Volume] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shin-Jinbutsuoraisha Co.,Ltd. 1990.

- 豊橋市史 [History of Toyohashi City] (in Japanese). 8. Toyohashi, Japan: Toyohashi City Board of Education. 1979. ASIN B000J8HTNY.

- Toyama, Misao; Morimatsu, Toshio (1987). Guide to the Organization of the Imperial Army (in Japanese). Fuyoushobou Publishers.

- Hara, Takeshi (2002). 明治期国土防衛史 [History of National Defense in the Meiji Period] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Kinseisha.

- Humphreys (1995), p. 150.

- Hata, Ikuhiko (2005). Comprehensive Encyclopedia of the Army and Navy of Japan (in Japanese). 2. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

- Madej, W. Victor (1981). Japanese Armed Forces Order of Battle, 1937–1945. Allentown, PA.

- Gailey (1988), p. 36.

- Hoyt (1980), p. 240.

- Nevitt, IJN Asashimo. Accessed 31 May 2011.

- Nevitt, IJN Kishinami. Accessed 31 May 2011.

- Nevitt, IJN Okinami. Accessed 31 May 2011.

- Gailey (1988), p. 37.

- Toyama, Misao (1981). 陸海軍将官人事総覧 陸軍篇 [Survey of Flag Officers of the Army and Navy: Army Volume] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Fuyoushobou Publishers.

- Crowl (1959), p. 453.

- Jones (1986).

- Gailey (1988), p. 89.

- Gailey (1988), pp. 90–112.

- Gailey (1988), p. 129.

- Gailey (1988), p. 130.

- Gailey (1988), p. 132.

- Gailey (1988), p. 134.

- Gailey (1988), p. 135.

- Gailey (1988), p. 136.

- Gailey (1988), p. 138.

- Gailey (1988), p. 142.

- Ito (1998), p. 87.

- "Traces of Camp Toyohashi" [軍都豊橋の面影]. Hojo Junior High School Official Website (in Japanese). 2008. Archived from the original on 16 August 2004. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- "Saipan: Memorial to the Japanese War Dead" [サイパン/日本人戦没者の碑]. Saipan Sightseeing Map (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- Hyodo (1994), p. 475.

Bibliography

- Crowl, Philip A. (1959), Campaign in the Marianas, U.S. Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific, Washington, DC: Department of Defense, archived from the original on 27 December 2010, retrieved 6 January 2011

- Gailey, Harry (1988). The Liberation of Guam 21 July – 10 August. Novato, CA: Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-651-X.

- Hoyt, Edwin P. (1980). To the Marianas: War in the Central Pacific: 1944. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company.

- Humphreys, Leonard (1995). The Way of the Heavenly Sword: The Japanese Army in the 1920s. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2375-3. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- Hyodo, Masao (1994). History of the 18th Infantry Regiment [歩兵第十八聯隊史] (in Japanese). Toyohashi, Japan: 18th Infantry Regiment History Publication Society.

- Ito, Masanori (1998). The End of the Imperial Army [帝國陸軍の最後] (in Japanese). 3. Tokyo: Mitsuto Company.

- Jones, Don (1986). Oba, The Last Samurai: Saipan 1944–1945. Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-245-X.

- Nevitt, Allyn D. (1998). "Long Lancers". Imperial Japanese Navy Page. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

External links

![]() Media related to 18th Infantry Regiment (Imperial Japanese Army) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to 18th Infantry Regiment (Imperial Japanese Army) at Wikimedia Commons