1888–1893 Uprisings of Hazaras

The 1888–1893 Uprisings of Hazaras occurred in the aftermath of the Second Anglo-Afghan War, when the Afghan Emirate signed the Treaty of Gandamak. Afghan King Abdur Rahman Khan set out to bring the Turkistan, Hazarajat and Kafiristan regions under his control. He launched several campaigns in the Hazarajat due to resistance from the Hazaras, and he conducted a genocide which included killing and raping of Hazaras. Sixty percent of the total Hazara population was killed or displaced with thousands fleeing to Quetta and other adjoining areas. The Hazara land was distributed among Pashtun villagers. Hazara women and old men were sold as slaves, and many young Hazara girls were kept as concubines by Afghan kings.[3] Abdur Rahman arrested Syed Jafar, chief of the Sheikh Ali Hazara tribe, and jailed him in Mazar-e-Sharif. The repression after the uprising has been called the most significant case of genocide in the history of modern Afghanistan.[1]

| Crackdown on the Third Hazara Uprising | |

|---|---|

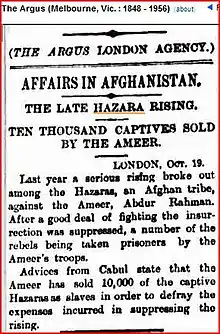

London backed newspaper documenting the selling of 10,000 Hazaras as slaves in Cabul. | |

| Location | Hazarajat, Afghanistan |

| Date | 1893 |

| Deaths | 60 to 70 thousand Hazara families[1][2] |

| Perpetrators | Afghan army under Abdur Rahman Khan |

First uprising

The first Hazara uprising against Abdur Rahman Khan took place between 1888 and 1890. When Emir Abdur Rahman's cousin, Mohammad Eshaq, revolted against him, tribal leaders of the Sheikh Ali Hazaras joined the revolt. The revolt was short lived and crushed as the Emir extended his control over large parts of Hazarajat. Leaders of the Sheikh Ali Hazaras had allies in two different groups, Shia and Sunni. Abdur Rahman took advantage of the situation, pitting Sunni Hazara against the Shia Hazara, and made pacts among the Hazara.

After all of Sheikh Ali Hazaras' chiefs were sent to Kabul, opposition within the leadership of Sawar Khan and Syed Jafar Khan continued against the government troops, but at last were defeated. Taxes were imposed and Afghan administrators were sent to occupied places, where they subjugated the people with abuses.[4] People were disarmed, villages were looted, local tribal chiefs were imprisoned or executed, and the better lands were confiscated and given to Afghan nomads (Kuchis).[5]

Second uprising

The second uprising occurred in the Spring of 1892. According to Syed Askar Mousavi, the cause of the uprising was an assault on the wife of a Hazara chieftain by Afghan soldiers. The families of both the man and his wife killed the soldiers involved and attacked the local garrison.[4] Several other tribal chiefs who supported Abdur Rahman now turned against him and joined the rebellion, which rapidly spread through the entire Hazarajat. In response to the rebellion, the Emir declared a "jihad" against the Shias [6] and raised an army of up to 40,000 soldiers, 10,000 mounted troops, and 100,000 armed civilians (most of whom were Pashtun nomads).[4] He also brought in British military advisers to train his army.[5]

The large army defeated the rebellion at its center, in Oruzgan, by 1892 and the local population was displaced with some being massacred.

"thousands of Hazara men, women, and children were sold as in the markets of Kabul and Qandahar, while numerous towers of human heads were made from the defeated rebels as a warning to others who might challenge the rule of the Amir".[4]

— S. A. Mousavi

Abdur Rahman ordered that all weapons of the Hazara be confiscated and for Sunni Mullahs to impose Sunni interpretation of Islam.[1]

Third uprising

| Part of a series on |

| Hazara people |

|---|

|

|

About · The people · The land · Language · Culture · Diaspora · Persecutions · Tribes · Cuisine Politics · Writers · Poets · Military · Religion · Sports · Battles |

The third uprising of Hazara was in response to excessive taxation,[7][8] starting in early 1893. This revolt took the government forces by surprise and the Hazara managed to take most of Hazarajat back. During the revolt the Hazaras arrested or killed the governor of Gizu;[9] the governor of Uruzgan tried to plead to the Hazaras that the Amir would listen to their demands.[9] The provincial forces responded to the revolt with military force; in this response the Hakim of Gizu reported to the governor general of balochistan that General Mir Atta Khan at Gizu committed "great excesses" in Gizu.[10] After the revolt unfolded; Hazara tribal leaders like Muhammad, Karbala-i-Raza and others were arrested after trying to flee.[11] Abdur Rahman kept various Hazara chiefs as hostages in Kabul; yet eventually sent them back to Uruzgan;[12] after the revolt was crushed they were then sent back to Kabul again.[13] After months of fighting, the uprising Hazaras were eventually defeated due to a shortage of food; in response to such food shortages Abdur Rahman ordered grain be sent from Herat to Uruzgan.[14] Small pockets of resistance continued to the end of the year as government troops committed atrocities against civilians and deported entire villages.[5] The governor of Balochistan reported to the foreign department of India that he believed Abdur Rahman was intending to exterminate the Hazaras.[15]

Massive forced displacements, especially in Oruzgan and Daychopan, continued as lands were confiscated and populations were expelled or fled. Out of 132,000 families, 10,000 to 15,000 Hazara families fled the country to northern Afghanistan, Mashhad (Iran) and Quetta (Pakistan), and 7,000 to 10,000 Hazaras submitted to Abdur Rahman, and the rest fought until they were defeated.[1][4] There is a famous story of 40 Hazara girls in Uruzgan committing suicide to escape sex slavery during the persecution.[16] 30 mule loads;[17] or roughly over 400 decapitated Hazara heads[N 1] were allegedly sent to Kabul. The Sultan Ahmad Hazara tribe of Uruzgan was reduced from 3,000 families to just 60 by the repression of Abdur Rahman.[1] 68% of the Beshud Hazara tribe was killed or displaced by the Amir's crackdown.[1] It is estimated that more than 60%[20] of the Hazara population were massacred or displaced during Abdur Rahman's campaign against them. Hazara farmers were often forced to give up their property to Pashtuns and as a result many Hazara families had to leave seasonally to the major cities in Afghanistan, Iran, or Pakistan in order to find jobs and a source of income. Quetta in Pakistan is home to the third largest settlements of Hazara outside Afghanistan. Syed Askar Mousavi, a contemporary Hazara writer, estimates that more than half of the entire population of Hazarajat was driven out of their villages,[4] including many who were massacred. Encyclopædia Iranica claims: "It is difficult to verify such an estimate, but the memory of the conquest of the Hazārajāt by ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān Khan certainly remains vivid among the Hazāras themselves, and has heavily influenced their relations with the Afghan state throughout the 20th century."[4] In 1894 802 Hazara leaders who survived the rebellion were killed or exiled after being captured.[1]

Others claim that Hazaras began leaving their hometown of Hazarajat due to poverty and in search of employment mostly in the 20th century.[21] Most of these Hazaras immigrated to neighbouring Balochistan, where they were provided permanent settlement by the government of British India.[22] Others settled in and around Mashad, in the Khorasan Province of Iran.[21]

Notes

References

- Ibrahimi, Niamatullah (2017). The Hazaras and the Afghan State Rebellion, Exclusion and the Struggle for Recognition.

- دلجو, عباس (2014). تاریخ باستانی هزاره ها. کابل: انتشارات امیری. ISBN 978-9936801509.

- http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/hazara-2

- Alessandro Monsutti (15 December 2003). "HAZĀRA ii. HISTORY". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- Mousavi, Sayed Askar (1998) [1997]. The Hazaras of Afghanistan: An Historical, Cultural, Economic and Political Study. Richmond, NY: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-17386-5.

- "Refworld | World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – Afghanistan : Hazaras". Refworld. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- News.D.No.48 F. No.124 F.C.,dated Sibi, 27 January 1893. From-Major-General Sir James Browne, K.C.S.I.,C.B.,R.E.,Agent to the governor-general in Baluchistan, To-The Secretary to the Government of India, Foreign Department. News-Letter No 3,

- News.D.No.128 F. No.1537, dated Quetta, 24 March 1893. From-Major-General Sir James Browne, K.C.S.I.,C.B.,R.E.,Agent to the governor-general in Balochistan, To-The Secretary to the Government of India, Foreign Department. News-letter No.11, By Khan Bahadur Mirza Muhammad Takki Khan, 17 March 1893.

- News.D.No.186 F. No.2257, Quetta, 28 April 1893, From-Major-General Sir James Browne, K.C.S.I.,C.B.,R.E.,Agent to the governor-general in Baluchistan, To-The Secretary to the Government of India, Foreign Department. News-letter No.16, By Khan Bahadur Mirza Muhammad Takki Khan, 21 April 1893.

- News.D.No.29 F. No.26 F.C.,dated Camp Jacobabad, 14 January 1893. From-Major-General Sir James Browne, C.B.,K.C.S.I., R.E.,Agent to the governor-general in Baluchistan, To-The Secretary to the Government of India, Foreign Department. News-letter No.1, By Khan Bahadur Mirza Muhammad Taki Khan, 6 January 1893.

- News. D.No.85 F. No.300 F.C., dated Sibi, 25 February 1893. From-Major-General Sir James Browne, K.C.S.I.,C.B.,R.E., Agent to the governor-general in Baluchistan, To-The Secretary to the Government of India, Foreign Department. News-letter No.6., By Khan Bahadur Mirza Muhammad Takki Khan, 10 February 1893.

- News.D.No. 242. F. No.2909,dated Quetta, 5 June 1893. From-Major-General Sir James Browne, K.C.S.I.,C.B.,R.E.,Agent to the governor-general in Baluchistan, To-The Secretary to the Government of India, Foreign Department. News-letter No.21, By Khan Bahadur, Mirza Muhammad Takki Khan, 27 May 1893.

- News. D.No.390 F. No.921. F.C., dated Ziarat, 11 September 1893. From-Major-General Sir James Browne, K.C.S.I.,C.B.,R.E.,Agent to the governor-general in Baluchistan, To-The Secretary to the Government of India, Foreign Department. News-letter. No.34, By Khan Bahadur Mirza Muhammad Takki Khan, 26 August 1893.

- Diaries.D.No 62, No. 177 F.C., dated Sibi, 6 February 1893. From-Major-General Sir James Browne, K.C.S.I., C.B., R.E., Agent to the governor-general in Baluchistan, To-The Secretary to the Government of India, Foreign Department. News-letter No.4, By Khan Bahadur Mirza Muhammad Takki Khan, 27 January 1893,

- News.D.No.243 F. No.2903, dated Quetta, 5 June 1893. From-Major-General Sir James Browne, K.C.S.I.,C.B.,R.E.,Agent to the governor-general in Baluchistan, To-The Secretary to the Government of India, Foreign Department. News-letter No.20, By Khan Bahadur Mirza Muhammad Taki Khan, 19 May 1893.

- "Chehl Dukhtaro". Hazara.net. Archived from the original on 7 November 2019.

- Gier, Nicholas F. "THE GENOCIDE OF THE HAZARAS Descendants of Genghis Khan Fight for Survival in Afghanistan and Pakistan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Mule". Encyclopedia.com.

- Brain, Marshall. "How much does the human head actually way?". Brainstuff.

- Bussi, Pierluigi. "IL GENOCIDIO DEGLI HAZARA". Kim International Magazine. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019.

- "HAZĀRA". Arash Khazeni, Alessandro Monsutti, Charles M. Kieffer. United States: Encyclopædia Iranica. 15 December 2003. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- "Who are the Hazara". Pak Tribune. Retrieved 3 April 2012.